How to Get Out of a Slump, and Handle Pressure Situations Calmly

It turns out that you can get out of a slump or handle pressure situations comfortably by merely changing your facial expressions. I have been trying this over the past several days and have been completely stunned with what happens.

Background

This is not my own theory. In Blink, Malcolm Gladwell talks about a mind reader, Silvan Tomkins, who can see and interpret the expressions on people's faces so well that he seems to read their minds. He can pick up on the microcosmic muscular movements of the brow, lips, chin, and understand the emotion it represents.

Tomkins' mind-reading capability was so shocking that two psychology researchers, Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen, undertook a detailed study of every facial expression possible and its meaning. Their research culminated in a 500 page document titled Facial Action Coding System (FACS).

For example, they discovered that facial expressions made by “contracting the muscles that raise the cheek (orbicularis oculi, pars orbitalis) in combination with the zygomatic major, which pulls up the corners of the lips” indicate happiness (Gladwell p. 204).

Research Leads to Unexpected Findings

As Ekman and Friesen researched the different facial muscular movements, they began to realize that just making the facial gestures affected their emotional state.

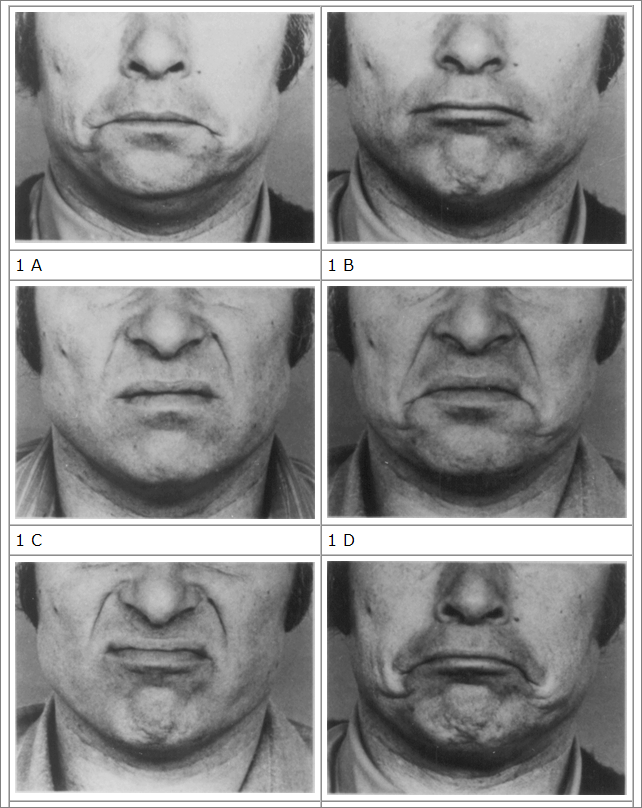

For example, making an angry facial expression caused their heart rate to start beating faster and their hands to get hot. When they made expressions of sadness or anguish, they started feeling bad inside. The image below is from Ekman and Friesen's FACS.

Their conclusion?

“What we discovered is that the expression alone is sufficient to create marked changes in the automatic nervous system" (Gladwell p. 206)

Gladwell further summarizes their findings by saying,

“The information on our face is not just a signal of what is going on inside our mind. In a certain sense, it is what is going on inside our mind.”

What's extraordinary about this claim is the reversal of causes and effects. We're used to thinking our emotions cause our facial expressions. And that's probably true. But the expressions can also cause our emotions.

A Study that Solidifies the Hypothesis

Gladwell records that a group of German psychologists conducted a study that solidified the idea about facial expressions affecting emotional states. Gladwell writes,

“[The psychologists] had a group of subjects look at cartoons, either while holding a pen between their lips – an action that made it impossible to contract either of the two major smiling muscles, the risorius and the zygomatic major – or while holding a pen clenched between their teeth, which had the opposite effect and forced them to smile. The people with the pen between their teeth found the cartoons much funnier…. What this research showed, though, is that … [e]motion can also start on the face. The face is not a secondary billboard for our internal feelings. It is an equal partner in the emotional process." (pgs. 207-08)

If you try holding a pen between your lips, the world does look a bit gloomier.

Comparison to Pavlov's Dogs

The idea of facial expressions causing emotional states may be hard to believe, but if you remember Pavlov's salivating dogs, the reversal of cause and effect is more understandable.

The idea of facial expressions causing emotional states may be hard to believe, but if you remember Pavlov's salivating dogs, the reversal of cause and effect is more understandable.

Ivan Pavlov triggered a conditional reflex (salivation) in his dogs by consistently ringing a bell before giving them food:

“If the bell was sounded in close association with their meal, the dogs learnt to associate the sound of the bell with food. After a while, at the mere sound of the bell, they responded by drooling." (nobelprize.org)

In other words, even without the presence of food, they began to salivate because they heard the bell. Our facial expressions are like the bell. Even without the emotional state, the brain notes the expression [hears the bell] and triggers a conditional reflex in our emotions.

Applying All This to Get Out of a Slump

On a more personal note, I've been in a basketball slump lately. For about the past six months, my shot has been off, and I haven't been able to figure out what's wrong. I've been playing less frequently, practicing less (ever since I started podcasting, actually). When I'd jump into a pickup game, I'd become a bit tense and nervous because I couldn't play at my normal level.

On a more personal note, I've been in a basketball slump lately. For about the past six months, my shot has been off, and I haven't been able to figure out what's wrong. I've been playing less frequently, practicing less (ever since I started podcasting, actually). When I'd jump into a pickup game, I'd become a bit tense and nervous because I couldn't play at my normal level.

Then last week I started thinking about Blink. Gladwell talks about situations where our unconscious judgment fails us. One of those situations is high stress/arousal. He explains that many police departments have banned high speed chases because it puts the police officer in such a high state of stress/arousal, they consequently make poor decisions.

For example, several riots (including the Rodney King beating) took place because of police officers' decisions after a chase. Police simply don't make good decisions when their adrenaline is pumping and their heart rate is racing. This is because, Gladwell explains, the body's evolutionary response to threats is to minimize all sensory intake (such as sound or touch) not relevant to the threat at hand. The sensory distortion may be what impairs our judgment.

In any case, he says after your heart rate goes past 145 beats per minute, our brain starts to go downhill. He quotes Dave Grossman, author of On Killing:

“At 175, we begin to see an absolute breakdown of cognitive processing … The forebrain shuts down, and the mid-brain … reaches up and hijacks the forebrain…” (226).

Gladwell continues:

“Vision becomes even more restricted. Behavior becomes inappropriately aggressive. .. Blood is withdrawn from our outer muscle layer and concentrated in core muscle mass. The evolutionary point of that is to make the muscles as hard as possible – to turn them into a kind of armor and limit bleeding in the event of injury. But that leaves us clumsy and helpless.” (226-27)

Most of the high stress/arousal states Gladwell explores involve police chases, shootings, dialing 911, and other life or death situations. But I think the same thing happens on the basketball court – someone passes you the ball, 9 other guys shift positions on the court, your defender closes in and swipes at the ball, the score is tied, a lot of people are looking on, teammates are moving quickly, raising their hand for the ball, you unconsciously consider paths to the basket, or shooting options. Not a lot of conscious analysis goes on, and when your heart is racing at 160 beats a minute, your sensory perception declines and your shot, which may have been right on target during casual practice, suddenly misses the rim.

The last time I found myself in this situation – my slump – I remembered the cartoon experiment from the German psychologists, and I squeezed out a smile. Whenever I got the ball, I smiled – not a big cheesy grin, because that's not authentic for me. But a moderate I'm-happy smile.

To my surprise, I became more relaxed, felt less anxiety, and my shots started to fall. My shot started coming back!

High Pressure Situations

I found the technique worked on more than a basketball court. A couple of days later, I had to deliver a brown-bag presentation on a software project I'd documented at work. I was a little nervous, so I made an effort to smile, similar to when I was shooting on the basketball court.

After 5 min. or so, I started to feel comfortable and relaxed. Instead of a stiff, forced, or defensive demeanor, I was calm as can be, moving effortlessly through the presentation and enjoying the questions participants asked.

Yet Another situation

The other two situations may have been chance, but the other morning I had yet another experience.

Foolishly, I was upset at my wife because we were late to church. About 10 minutes after sitting with contempt on the pew, I tried smiling. It actually hurt to smile. I kept trying – why would merely making a facial expression be so difficult, if it weren't applying some torque to change my inner state of emotion?

After several smiling minutes, I came to my senses and was content again, acknowledging to her that the fault for being late was mine.

Conclusion

When we are happy, we are relaxed. Our heart rate isn't racing, our muscles aren't stiffening, and we can think and respond clearly. Our sensory perception is acute, and our performance increases. We can partially induce this state through a facial expression of happiness. Our brain associates the facial expression with the emotion, and fosters it where it was previously absent.

So the next time you're in a slump, or are walking into a high-pressure situation, clench a pencil in your teeth, or contract the muscles that raise the cheek, pull up the corners of your lips. You can trick your brain into triggering a more advantageous emotional state. Within a few minutes you'll find you no longer have to try — the smile forms naturally.