Writers See Stories Where Others Don't

Last week I had the opportunity to listen to Chad Hymas, an inspirational speaker (not the Chris Farley type), who related several powerful stories that changed him. A quadriplegic after a tractor-hay bale incident, Hymas shared how one can live a happier, more fulfilled, more productive life even without the use of one's limbs.

We all sat mesmerized while Hymas related story after story. His speech wasn't polished or his diction articulate, but his life-altering stories held me at full attention. As I walked back to my department, I wondered how he had become a motivational speaker. Was it the handful of life-altering stories, which he could deliver in sincere, moving ways, that made him inspirational? I thought, perhaps if I had a handful of life-altering stories …

But later I realized Hymas probably didn't have more stories than anyone else. There are hundreds of other quadriplegics, others who have broken their necks, who are no doubt dull, unmotivating, and ordinary.

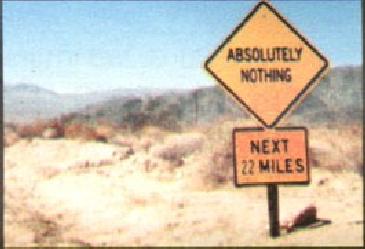

What separates extraordinary presenters and writers from others? I believe it's the ability to see stories where others miss them. The ability to create stories where others look at the obvious and see nothing.

This week I've been reading a book of essays by James Hall, a contemporary Florida novelist. In one of his essays, Hall explains how that his love for reading stemmed from a murder mystery called Nude Woman in the Grass, a book he randomly found in the library and started reading when he was ten. The smutty-sounding title (which turned out to be very PG) grabbed his attention, but he found the mystery gripped him, and led him to see the appeal of reading. He writes,

“So this was why people read! Books were about adult things. Strong emotions, extreme behaviors, the inside stuff of a world I had never imagined existed. In this my first recreational book I suddenly realized that novels could fill one with heart pounding fear as well as lip-smacking lust. That they could, in fact, suddenly expand the boundaries of the tiny hillbilly town where I had always lived and where I imagined I would always stay.”

Hall's experience was quiet, subtle, and mostly stationary -- he was merely reading a book in a library. But within this one moment, he sees a larger, more meaningful narrative.

The writer's ability to see story where others pass it by is similar to the photographer's eye. When I take photos, I merely point and click, and don't think much about what I'm doing. But real photographers, I've been told, look for the single moment that tells a story -- the one split second where someone's countenance tells the story of the whole. Novices don't see this. The captured moment is something you must learn to see. The photographer sees the invisible story and captures it.

Yesterday Shannon and I rode our bikes through some winding roads in Eagle Mountain, passing by rustic 9,000-square-foot ranch homes, many with horses in the sides of their yards and four car garages. The sun was setting over the mountain hills. I was pulling all three kids in a bike carrier behind me.

Nothing happened on the ride, but I felt, in a few distinct moments, that we had found a place we could call home. After years of living all over the world, and months of searching for the right place, we found the right place.

I started to see how I might create a story out of an experience that didn't seem to include a story. We were, after all, just riding our bikes. No one was injured. No one broke world records. No one even talked much. But I caught a glimpse of the narrative that was going on, almost invisibly before us.

--------

photo from SAAO