Finding Business Models in the Economics of Free

On the web, the standard economic model is to give products away for free -- from storage to email, music, news, access, and other information. For companies to survive in an economy of free, they have to spin their business models in creative ways, finding profits indirectly, such as through lite/pro versions, cross-subsidies, advertising, or appeals to the attention economy. In the economics of free, writers face particular challenges because their product is information, which is often intangible, and the intangible is almost always free.

Experimenting with Free

My sister is up from Florida visiting this week, and we've been talking about iPhone apps, because her husband already created a couple apps, and their million-dollar app idea is just around the corner. My brother-in-law Sean's first iPhone app, Box of Socks, sold for 99 cents, like most others. Not seeing much profit, he decided to release a lite, single-level version version for free. During the first week, he saw a 50% increase in sales, but after the week, sales returned to normal.

His other application, Tap Dots, ran a similar course. After three months, the application had 400 downloads. Discouraged by the lack of success, he decided to make the entire application free. As a free app, he had 3,000 downloads in four days.

One attempt in making the application free, Sean explained, was to bump up the product's visibility. If you can get in the top 25 most popular downloads, the sales of your app take off dramatically, because people look for new apps in this top 25 list. The more people download your app, the more visibility you receive, and the more visibility you receive, the more people download your app -- the process feeds on itself and pushes you upward. The free giveaway is just one technique to try to move into that hyper-downloaded space.

Why People Expect Free

In Free! Why $0.00 is the Future of Business, Chris Anderson, editor in chief of Wired magazine, explains, "The moment a company's primary expenses become things based in silicon, free becomes not just an option but the inevitable destination." In other words, products and services on the web are trending toward free, partly because technology costs for bandwidth, storage, and information processing are decreasing rapidly.

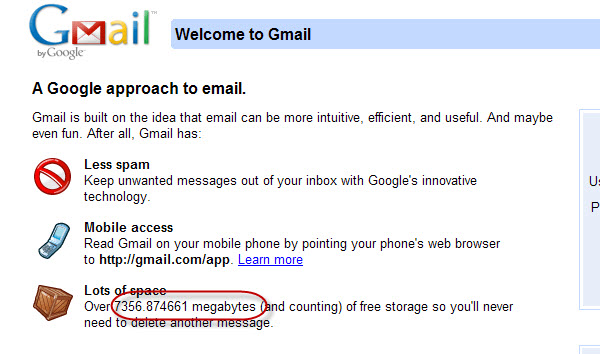

For example, storage with web hosts, such as Blue Host, is now unlimited. And when you sign up for a Gmail account, you can see your allowed storage space increase by the second.

The lowered cost of online services is a driving factor behind the sensibility that almost everything on the web should be free.

Finding Business Models in Free

Given the trend toward free, how are companies leveraging "freeconomics," as Anderson calls it, to turn a profit? Anderson describes various models:

Freemium: Give users a lite (free) and pro (paid) version. Or hook users on free samples or a 30-day version with the hope that they end up springing for the paid version later.

Advertising: Provide the product for free and make money by selling advertising.

Cross subsidies: Lure your audience to your site with free products and hope that, once on your site, the visitors will buy other products that yield profit.

Zero marginal cost: Distribute products or content for free because no one will pay for the content, no matter what you do. Do it out of a love of doing it, and because it costs you nothing. (This is basically my model.)

Labor exchange. Give products or services away for free, but as people use the product, earn value from their usage. For example, Goog 411 -- Google's free directory assistance -- is really a clever way to collect voice-recognition data for a voice-driven search engine for mobile phones.

Gift economy. Give something away for free out of either altruism or the expected rewards of sharing ("I share with you, you share with me").

Anderson also explains how some companies give a product away for free but then charge for necessary components -- for example, they install a fancy coffee machine in an office for free, but then charge for the coffee. Or they give away a phone for free but charge for the service contract. Or they sell a printer for almost nothing but then make money off the ink cartridges.

Anderson also discusses free as a means of gaining ground in the attention economy. Give the product away for free, gather a large audience, and figure out a business model later. "There is, presumably, a limited supply of reputation and attention in the world at any point in time," Anderson says. "These are the new scarcities — and the world of free exists mostly to acquire these valuable assets for the sake of a business model to be identified later." In this sense, rather than financial profit, you receive an increased amount of attention as your reward. You can later use this hold on attention to pitch services or influence buying decisions.

Organizational Structures and Free

I recently participated in a Social Media Task Force for the STC that included some discussions about how to handle the economy of free. My role on the task force was to give advice to the STC on blogging. I initially wanted the STC to convert Intercom into a freely accessible online model, such as Smashing Magazine, with the idea that visibility would grow readership, and growth in readership would convert to increased membership.

But as I was reading about the struggles newspapers have in charging for access to content, I realized that STC's traditional organizational structure can't support a model that gives away information -- one of its core products -- for free. To make it in the economy of free, organizations need to be lighter, more virtual. John Gruber explains:

Undeniably, there is money to be made in digital publishing with free reader access, but whether that revenue leads to profits depends upon the scale and scope of the organization. The potential revenue does not appear to be of the magnitude that will support the massive operations of existing news organizations. What works in today's web landscape are lean and mean organizations with little or no management bureaucracy — operations where nearly every employee is working on producing actual content. I'm an extreme example — a literal one-man show. A better example is Josh Marshall's TPM Media, which is hiring political and news reporters. TPM is growing, not shrinking. But my understanding is that nearly everyone who works at TPM is working on editorial content.

Old-school news companies aren't like that — the editorial staff makes up only a fraction of the total head count at major newspaper and magazine companies. The question these companies should be asking is, "How do we keep reporting and publishing good content?" Instead, though, they're asking "How do we keep making enough money to support our existing management and advertising divisions?" It's dinosaurs and mammals.

And it's not really surprising that they're failing to evolve. The decision-makers — the executives sitting atop large non-editorial management bureaucracies — are exactly the people who need to go if newspapers are going to remain profitable. (Charging for Access to News Sites)

Only organizations that are light in employees, probably distributed virtually, with low operating costs and other marginal expenses can succeed in an economy of free. Traditional structures with heavy management, large office spaces, expensive operating costs, and excessive employees are not going to make enough money to support their costs if they give away their products for free. But if they can't provide at least some of those products for free, they also can't make it.

Ominous Signs Ahead for Writers

iPhone apps seem to be the latest get-rich-quick idea online. But program code is a bit different from information. When you download an iPhone application, you seem to get something tangible. Information, on the other hand, tends to be perceived as free because you often don't get anything you can hold in your hand and say, yes, I paid for that (except e-books). For example, this blog post took me a couple of hours to write, but I doubt any reader feels an obligation to pay for it. Information doesn't seem like something people need to give money for, because they're literally getting no-thing in return.

Because of the intangibility of our product, writers are in a bad market. We're moving further and further into a web economy in which words are not something people pay for. As a somewhat extreme example, last month someone offered to pay me $1.25 to write a press release.

I don't have a magic formula for spinning the economics of free into a profitable business model. But I do agree strongly with Anderson's assertions about the value of the attention economy. In a world of increasing numbers of information sources, our time and attention are growing scarcer. We can only have so many feeds in our feedreader, so many people to follow on Twitter or Facebook before we say, enough. Gaining a chunk of that attention can provide you with influence now and access to a business model later.