Why Tech Comm Is a Career Path of Last Resort for Students

While on my trip to BYU Idaho last week, I had an epiphany about why tech comm will always be the career path of last resort for students. As you recall, one of my desires was to open students up to the possibility of a career in tech comm, not as a sellout/fallback career, or a career of last resort, but one that they would actively seek and strive for because of the multifaceted appeal of the technical communication career itself.

When I started the presentation, only two of the students in the room (out of about 30) said they wanted to be technical writers. Nearly half or more wanted to be editors. I'm not sure what the rest had in mind. (The creative writers and literature students weren't even present.) I presented about tech comm, stressing all the various specializations and perspectives of the profession that go beyond click this, select that instructional writing.

Later that evening, the conference organizers took us to a Thai restaurant in town (surprisingly good for small-town Rexburg). My wife and I sat next to the son and daughter-in-law of Terryl Givens, a well-published scholar of Mormon Studies. The other conference invitee, Lynn Stegner, author of several novels, had to leave earlier in the afternoon.

While we were talking with Terryl's son, a student at BYU, he mentioned that his emphasis was creative writing (one of five emphases in the English major). I explained that I was a technical writer. There was a long pause, and then someone changed the subject. In mentioning technical writing, there was absolutely no sign of interest in the student's face. It was then that I realized something.

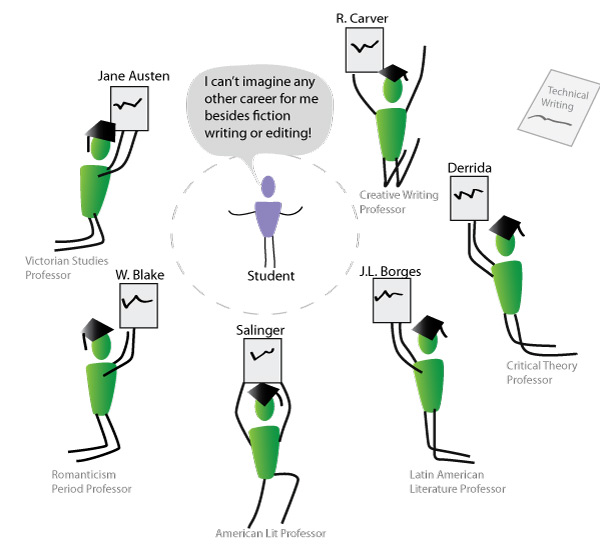

In almost every university, the English curriculum is run by literature professors and writers who teach students from day one to appreciate, study, and ponder good literature. Writers are elevated as gods in the halls of English departments. To publish a novel is the very definition of success, the pinnacle of artistic and creative achievement. Organizing a conference in which published writers and, in this case, scholars, present essays (such as "What it means to be a writer") and read excerpts of their works only helps us hold writers in high esteem. The entire river is flowing toward the creative direction, because that's the focus of the English curriculum: literature, creative writing, critical theory.

Somewhere down that path, literature professors feel an ethical responsibility to help students come to grips with reality. They realize that the job market for English professors is extremely tough. Publishing a novel is even more unlikely. Becoming an editor in a major New York publishing house is also a difficult path, and one that will likely start out in poverty and secretarial work for many years.

Given this, English professors add in a few practical courses, so that students can actually use their writing and analytical skills in a financially sustainable career. They add in a few classes on business and technical writing, computers and the humanities, and scientific/technical communication. But the classes are clearly not the professor's interest or strength. They're an assignment given to any professor who has an inkling of background in professional writing.

The tech comm classes take a backseat to Chaucer and Postmodernism and the latest novel that the English professor is drooling over. As such, the tech comm classes live up to the student's perception: they are, in fact, boring. The teacher isn't engaged by the material. The assignments are corny and unrealistic. It feels nothing like any of other English course. There aren't any stories driving the plot forward, no characters to fall in love with, no fascinating world views intricately interwoven into subtle narrative details.

In the English discipline, the flow of the river is moving towards the creative. How can we expect students to suddenly develop an interest in technical writing? To do so requires them to swim against the current, against the ideology that literature professors have inculcated so deeply into their students.

If our goal is to stoke the student's interest in tech comm, it's a battle we will never win if we fight it on the grounds of the English hallways.

In an essay on the Heart of Technical Communication, Bill Albing suggests that the solution is to decouple the tech comm emphasis from its subordinate position in the English major, and to position it on its own, perhaps even within a business setting. Bill writes:

There is this strange and persistent association of technical documentation with writing as taught in university English curricula. We need to break the connection with university English departments because they keep monopolizing the discussion about what is the core of our profession. What makes it a discipline is the business, the business value, the use of communication to allow business to operate, to make money, to accomplish its goals. The profession is too encumbered by its historical relationship to academic institutions that are steeped in the old paradigm, instead of to business, which is quicker at evolving. With their origin in academia and their continued association, many in the profession are afraid to step out and grab the baton and continue the race. The direction of technical communication is toward more complex relationships — relationships that are allowed in business but not well understood or encouraged by academia. The sooner we break those bonds, the sooner we can reestablish much needed newer ones that will help bolster our profession.

In other words, technical communication should not be taught in the context of an English department, because tech comm is about adding business value to customers, about developing relationships with users. This is not understood or encouraged in traditional English curricula.

I agree with Bill. I used to think the problem rested with me. If I could just present technical writing in an interesting enough light, if I could just show students that there's so much more than click-this, select-that, if I were just interesting enough myself in the way I showed my thinking processes and spontaneous analyses, I could convert students away from their futile literary dreams into a more practical, interesting, and sustainable career.

But as long as tech comm remains an emphasis within an English department -- a department full of literature professors who worship fiction authors and poets, and teach students to do the same -- that change of mindset will never happen. Tech comm will always be the career of last resort.