Topic Chunking and The Broken Alarm Clock

It's been about 9 days since my last post, and yesterday my colleague leaned over and asked why I hadn't been posting -- was something wrong? He himself has been working on a novel, so he hasn't posted anything for a month.

No, nothing is wrong. I always chuckle when I see blog posts in which people apologize for not posting on their blog, or when they provide reasons for their lack of blogging activity. I chuckle because it's like, hey, I didn't miss you. I have 1000+ unread posts in Google Reader and content overflowing on Twitter, books from Amazon, and other sources. There's no dearth of content on the web, so your short absence of content isn't something I've been agonizing over. I suspect the same is true for my readers.

If you really want to know, though, I've been exhausting my creating energy writing a debut article for work. I'm still waiting on the outcome, but it involved doing some historical research, and that kind of stuff you just can't crank out with clever typing.

Now, on to the broken clock. After my last post about rocks and cairns and chunking, some people thought it was funny that I went to Arches National Park and all I took were pictures of dinky rock cairns. So for those waiting for something more camera-worthy, check out Park Avenue.

And if you prefer people in your pictures, here I am skydiving off a rock in Sand Dune Arch.

I will spare you the 60 to 70 pictures of the baby crawling through the sand, as well as the other hundred pictures of my other kids doing all kinds of funny poses with rusty-orange arches in the background.

But digital pictures are not entirely irrelevant here. In David Weinberger's Everything Is Miscellaneous, he says the digital camera has encouraged people to take many more photos than they normally would. After a while you end up with thousands of photos on your hard drive, with almost no way to order or arrange them. Do I tag the above photo Arches? Utah? 2011? Jumping? Age 35? Soft sand? Rusty orange rocks? Sandstone? Falling? About the only thing you can do, without a specific metadata strategy, is tag the photo haphazardly. (I actually don't tag my photos at all, really. They just sit in various folders.)

But the scenario, if I were to tag my photos, is relevant to the ongoing discussion about chunking. The trend in previous comments I received was that your metadata strategy informs the size of each topic. If your metadata requires you to identify certain characteristics, then naturally your topic will need to be a certain size in order to accommodate that metadata. This makes sense to me.

But the most thought-provoking comment was by Mark Baker, who pointed me to a post on his site comparing granular topics to a broken clock. Mark says that as you start dismantling an alarm clock into its pieces, the pieces soon become meaningless in isolation. The broken clock is similar to a topic: the more granular it becomes, the less meaningful the topic becomes to readers. You also have less potential for attaching metadata to the topic. Mark explains:

Now start taking it [the alarm clock] apart. First you will disconnect various assemblies: the case, the clock mechanism, the ringer. Some of these, at least, could still have interesting metadata attached to them. But you continue, taking each of these assemblies apart until what you are left with is a collection of screws, gears, and several pieces of bent metal about which you can say nothing meaningful other than that they used to be part of an alarm clock. (Why Fine Chunking and Rich Metadata Don't Mix)

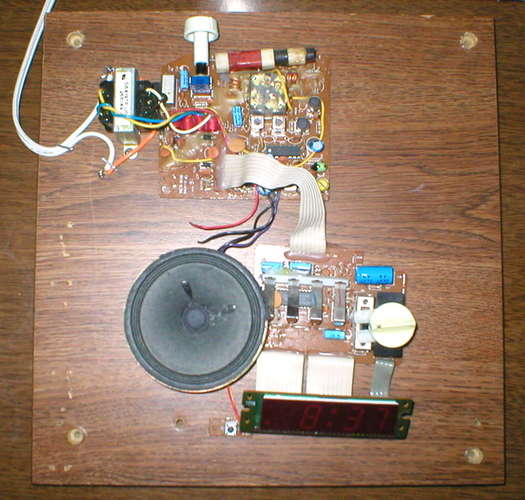

I couldn't find a picture of a disassembled alarm clock, but here's a flayed alarm clock below. You can see all the components here -- capacitors, transistors, wires, tubes, square things, bands, and other parts. Would it really be wise to isolate each one as a separate topic?

Keep in mind that the broken alarm clock is a metaphor, and all metaphors break down at some point. But it's quite a good metaphor since many of us do not understand the insides of alarm clocks. In fact, if you were to disassemble any technology in my house -- the refrigerator, a DVD player, a digital camera, an automatic pencil sharpener, etc, I probably couldn't make much sense of the individual components. They are meaningless in isolation.

A while ago I was reading DITA 101, by Ann Rockley, Charles Cooper, and Steve Manning. In the introduction, the authors assert that a well-written topic can stand alone in nearly any medium. A well-written topic is versatile in its placement, and is a logical unit in and of itself. It doesn't require much context to make sense.

To accomplish this self-contained unit of information, I think a topic has to be a fairly decent size. It probably wouldn't be a short standalone paragraph, nor would it likely be a short list of three steps. In my mind, it would be a somewhat sizable topic -- probably a conceptual description followed by a list of task steps. One needs a certain amount of substance to prevent the type of content that seems fragmented and incomplete to the user when viewed alone.

That's it for now. By the way, if you're going to the STC Summit, I'm giving a presentation titled Organizing Help Content: Breaking Out of Topic-Based Hierarchies on Tuesday at 4:00 pm. In it I hope to present the ideas I've been exploring in my Organizing Content series. Unfortunately my presentation is at the same time as Karen McGrane's We Are All Content Strategists Now and, judging from what I saw on Vimeo, she looks like a really good speaker. So my Summit audience may be a passing janitor and an assigned room monitor, but that's okay. Expect to see more posts in this series on my blog.

Also, I can see that the topics are moving toward metadata and taxonomy. If you have any good recommendations for books on metadata (in the context of technical communication), please let me know. I am finding that, despite the abundance of well-written blogs, books are sometimes more enjoyable to read in the long run.