Community and Collaboration (Wikis)

I've explained the most salient characteristics of wikis that will be of interest to technical writers. However, these are mostly tool-related characteristics. If you're the only person publishing to a wiki, there's little reason to actually use a wiki as a platform. The whole point in using a wiki is to capitalize on community and collaboration. This is the harder part of working with wikis, and it is what I will address now.

The potential reward in collaborating with the masses is an idea that shouldn't be underestimated. Almost everything interesting happening on the web comes about through community. Think of any well-known site. Its innovation isn't the technical features of the platform but rather the community. Wikipedia's genius is the collective contributions of so many different people working on an encyclopedia of all human knowledge. YouTube is a collection of community-contributed videos on virtually every subject. Twitter, Facebook, Linkedin, Craigslist, Pinterest – you name it, all of these sites are popular because of the community, not because of their site design or functionality.

Given that amazing things can happen through community and collaboration, it seems natural to adopt a similar model for documentation. Even on a small scale, if users can contribute just a small fraction of the content they contribute on these popular sites, wouldn't the endeavor be worth it? Certainly. But the real question is how you build a thriving, contributing community.

Spontaneous versus Directed Edits

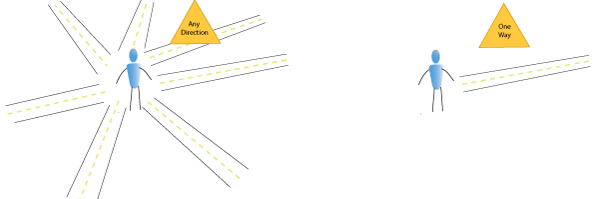

One of the first questions to address is how much autonomy you will give to community members. Will you allow them to do anything they want, or will you restrict their contributions to only those actions your company decides to allow?

Giving community members a lot of autonomy can increase their motivation to get involved. For example, with WordPress, a lot of community plugin developers have an itch they want to scratch, so they create plugins to satisfy specific needs they have. That's their motivation. But you may not want your community members creating code that strays outside of your company's direction.

When it comes to content, community members are usually less enthusiastic. If you simply include the ability for community members to edit content, but you don't direct or guide their efforts in any way, chances are they will not make a lot of spontaneous edits without some overriding collaborative purpose. Just adding an edit button in your documentation does little. In fact, I think many people give up on wikis when they find that almost no one edits the content.

If you want community members to more actively write and edit content, you may need to provide more direction. In a presentation at the STC Summit, Sarah Maddox explained that at Atlassian, they do regular doc sprints in which they carefully list out all the topics they need content written about, and then they make a request for people to write those topics. She said that it takes a lot of preparation to identify the topics, but the sprints are relatively successful.

Doc sprints are a popular method for getting community together to write content. I admit that I've never done a doc sprint. I have other methods for interacting with community.

The Wiki I Work With

The primary site I work with is LDSTech. LDSTech has a wiki, blog, and forum. One of the site's purposes is to allow community members to contribute their time and talents. LDSTech is a technology site for the LDS Church, so the community members are mostly LDS (Mormon).

According to a recent study, LDS church members contribute about 35 hours per month toward volunteer callings and other efforts. (Yes, that's about eight hours a week!) Providing a community where the more technical members could contribute using their writing and IT talent seems like a natural fit for such a volunteer-oriented community.

The LDSTech site has about 30 different projects that members can get involved in. Most of these projects do not involve writing. Rather, they involve beta testing applications, participating in design brainstorms, developing code for technical solutions, and other technical efforts.

I decided to create a project that would allow community writers to write for both the LDSTech blog and wiki. When a volunteer wants to get involved in a project, he or she navigates to the project page and clicks a Join button. His or her name is then added to the list of other project participants, and the project manager is notified that there's a new member.

Project managers can reach out to the new member and welcome him or her, and then assign a role to the volunteer (such as tester, writer, developer, project manager, database engineer, security engineer, or writer).

On average, there are about 100 volunteers on each of the projects, including the project to write for the blog and wiki. Many community members are interested and willing to help out. Figuring out work for everyone to do is actually the hard part.

To coordinate tasks, I use JIRA, a project and issue tracking tool from Atlassian. New members joining the project are automatically added to the project's JIRA instance as well as to a Google Group, which acts as a listserv for communication.

We use the blog to continually attract new members to the community. Overall, the model works pretty well. People interested in technology read the articles on the blog, which then presents them with opportunities to get involved in community projects. We don't have a problem in attracting more volunteers to join the community. The problem really is in figuring out the tasks to assign to volunteers.