Is Structured Authoring (like DITA) a Good Fit for Publishing on a Website?

5/22 update: This post generated a lot of controversy, and I believe part of the controversy could have been avoided if I had articulated my ideas better. I've gone through and updated parts of this post by adding notes. My additions appear in green.

The previous title was "Structured Authoring Versus the Web". However, of course the web uses structured authoring. Every web form in this post -- the title, body, category, tag, date, featured post -- are all forms that take their input and semantically identify the content. My original contention was the highly structured DITA format that is geared for content re-use and conditionalization. Hence the title change.

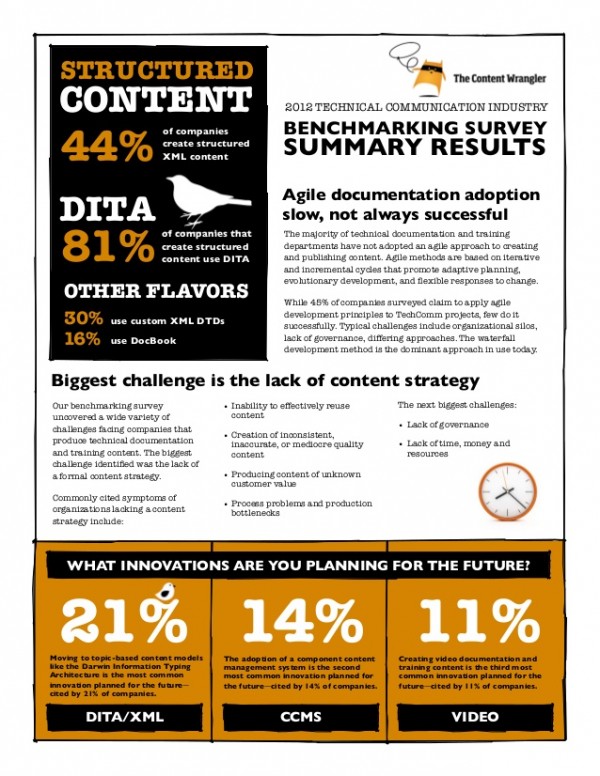

I recently listened to the Scriptorium webinar on the State of Tech Comm, which I found well-worth my time. One theme I keep hearing is a trend toward structured authoring. In Scott Abel's benchmarking survey (which the webinar uses as a starting point), Scott found that 44% of companies are using structured XML content, with 81% of those companies using DITA for their structure.

Clearly structured authoring is a trend with a lot of momentum. At the same time, structured authoring doesn't seem to include a website format. Mark Baker noted this absence of a website output in a discussion the other week. He said,

The thing is, at the moment, there are no structured authoring systems for the Web. DocBook was designed for book. DITA was developed for help systems. Both output to the Web, but they don't produce Web-like output. In fact, their output looks pretty much the same as the output from FrameMaker.

We have lots of unstructured platforms for the Web, but no structured platform. This is why I am developing SPFE — to be a structured writing architecture for the Web, and for EPPO.

Although structured authoring is no doubt a major trend in help, an even larger trend is the move toward the web. Given my love of the web and web-based platforms for authoring, I'm a little mixed about structured authoring methods like DITA. I wish structured authoring were more compatible with a web paradigm. In fact, I think the next evolution of structured authoring will involve a stronger integration with web platforms.

In this post, I'll pit structured authoring against the web and let the two go boxing for a while.

5/22 update: Note that when I say "web", I'm not referring to the tripane help or CHM help or HTML help that is formatted with HTML and published onto a website. I'm referring to an actual website, like the one you're reading now, or something like A List Apart or some other content heavy online site with comments, online content management, usually a database backend, tags, custom design, and more web-like features. Almost all tripane help (like this one) is contained in its own little frame that combines the content inseparably from its output format.

What is structured authoring?

First, a brief definition of structured authoring. Structured authoring involves applying a consistent pattern to your content, such as always following a specific sequence of tags.

Most structured authoring models use XML to define these tags. The tags are semantic in nature and don't include any formatting themselves. Instead, you use a transform language (XSLT) to apply formatting rules based on those tags. DITA, S1000D, and Docbook are all examples of structured authoring.

For a great explanation of structured authoring, see this white paper on Structured Authoring and XML from Scriptorium.

5/22 update: There are lots of varieties of structured authoring. In this post I'm referring mostly to DITA, not to all semantic tagging of content, HTML5, or some other markup. In tech comm communities, structured authoring usually refers to formatting content in a specific markup that is validated against a DTD before rendering it into an output. Of course there's lots of structure on the web and the web wouldn't be useful without structure. But does it make sense to use the DITA structure in publishing to a website? That's my real question here.

Why use structured authoring?

Structured authoring gives you several advantages:

Separation of content from format

By removing formatting tags from your content, you liberate your content to go into more places. You can output to an infinite variety of formats based on whatever transformation engines you can apply to your semantic tags.

In Meaning and Metadata, David Farbey relays Karen McGrane's advice in writing for mobile:

Don't encode meaning in visual styling

In other words, don't use a WYSIWYG editor to apply inline styling to your content. Most people agree that if you want to repurpose your content in more than one way, you need to separate the content from the visual display. Structured XML provides this separation of content from format.

Content re-use

Let's say you write Topic A and want to re-use the same topic in another output. You can create various maps (or tables of contents) that have different combinations of the content. You might create a map that includes only beginner topics, or one that's more comprehensive for administrators.

Your product might have various versions, with some topics applying to some versions but not others. By writing in small topics that can be combined in myriad ways, you have more flexibility for output combinations.

The reason these small topics are interchangeable is because they all have the same syntactically tagged structure and can be parsed predictably by the XSLT language.

Translation

If you need to translate your content, you'll need to have it in an XML format that a translation memory system can handle. XML formats make this export-and-import workflow a sane process to manage.

Universal format

If you acquire another company, you can easily integrate their documentation into your own, with your own branding and formatting, as long as their content (and your content) both use an XML format. When writers store content in XML, it can be exchanged and re-used more easily.

DITA was created by IBM in part to solve the problem of mergers and acquisitions that a large company like IBM regularly engages in.

Predictability

Structured content follows a predictable format that makes authoring easier. When readers can predict the format, it aids comprehension more quickly. It also reduces the number of decisions technical writers must make as they author content. The recipe model is often cited as an example here.

And in the other corner .... the web!

Clearly structured authoring has a lot of advantages with content. However, structured content has a hard time finding its way onto the web. Here are a few advantages of adopting a web platform for your help.

Transforming the structured XML content is a burden

Separating content from format has both advantages and disadvantages. Although you free the content to be output to any format, you also suddenly have a challenge now to define the XSLT rules behind that content transformation.

The PDF output from DITA is notoriously plain, and the web help HTML output is not usable by itself. You either need to hire a programmer to create your output for you, or you need to pass the output into another tool, like Flare, to transform your online output.

With many tech writing teams constrained with small budgets and few resources, hiring a dedicated publishing engineer to handle the transforms, or contracting out the work at a high cost, really isn't a practical solution.

Many web platforms already have a lot of attractive themes that writers can quickly leverage for a professional looking output. It's tempting to just adopt one of these web-based themes for help instead of defining one from scratch.

Websites provide better mobile display

One might think structured content leads to a better mobile workflow, since you can output content with a specific mobile view. The problem is that this model supposes that you should have a separate mobile output at all.

In contrast, responsive web design allows you to apply different stylesheets to the same content. The CSS3 style tags can be defined based on the viewport size of the user's browser. Just add div tags with unique IDs to your heart's content, and then you can style that content in different ways.

For example, this website has a mobile element to it. View it on your mobile device (or shrink the browser to a mobile-like size) and voila, the content responds to your device and still looks readable. You don't need to go to a separate site that has a separate output with a mobile transformation. There's just one source.

While you can generate a mobile output from structured content, you often end up with two different sites -- one for mobile viewers and one for regular viewers. The problem is that you can't determine what sort of device a person will use to arrive at your site -- smartphone, tablet, or computer. Therefore you can't always route people toward different sites, and even if you could, users often don't want a different version of the content. They want the full content.

It's possible to use structured content to generate a single responsive output for both desktop and mobile, but then what's the point of the multichannel output that structured authoring yields?

PDF formats mislead users

When people talk about the benefits of structured authoring, they often talk about the various outputs, saying you can output to desktop, mobile, PDF, Kindle, ePUB, and more.

But if you break down these options, very few help manuals need to be published to Kindle and ePUB. In most cases, a mobile view and a desktop would probably be just fine. What about PDF?

I don't offer a PDF output because I don't want users printing off help content. The last time I created long manuals, users would show them to me and not realize they were outdated. Users don't often know that help changes quickly.

In agile environments, help material potentially changes every two weeks. By giving users a PDF to print, you set up a situation for user frustration. As users follow the outdated manual and realize the steps are "inaccurate", they'll complain and your help will lose credibility. Better to maintain one source that is always up-to-date and online.

I think the PDF form is dying precisely because it doesn't keep pace with agile environments. Information changes too rapidly to hold any kind of lasting permanence through print. As an example, go to your local library and peruse the computer books section. Most of the books are new but at the same time outdated. You get the sense that the information is no longer the most current.

In cases where you really need to provide a PDF, you might be better off creating a quick reference guide that is an abbreviated (for example, 2-5 page) version of the help content, written in an introductory, condensed way. You could try single sourcing that quick reference guide, but it's usually more trouble than it's worth (compressing 200 pages into 2 pages requires a different style of writing -- one that is much more compressed).

Additionally, you can add a print stylesheet to your web pages. The print stylesheet usually strips off the navigation and any other web frames to provide the content only. You can also usually pull multiple pages into one printable view. For users who want to print content, this web printing capability might be just fine.

Content re-use is overrated

If all your help material is available on a single website, you have less of a need for content re-use. On a single web platform, there are different navigation options (tables of contents) based on different needs. And if one section needs the same information from another section, you simply link to the other section.

You don't generate a beginning and advanced guide on the same web platform, repeating topics across the site -- doing so would add a lot of confusion with search results, in addition to unnecessarily bulking up the documentation. For more on content re-use on a website, see What Does Content Re-Use Look Like in a Web CMS?

The one-platform-for-all-content model has some unique advantages. If users want to search for a term, the search looks at all content. You avoid the siloed situations that often result in No Results Found scenarios.

Additionally, all your content automatically inherits any change you make to your platform, so you don't have to regenerate 20 outputs when you make an update (to something like your copyright notice).

For more discussion on this topic, see Two Competing Help Models: One Stop Shopping or Specialized Stores.

Versions are going away with the cloud

If I had to support different versions of the same software, I could see more of a business case for content re-use. However, in the software as a service model (SaaS), your platform is generally in the cloud, so users generally don't have different versions of the software. You don't have to push updates and hope people upgrade (like Internet Explorer 8, 9, 10). We don't really live in that kind of world anymore.

Now software companies update their platform on a regular basis, and all companies who are subscribed to that service get the update automatically (because they didn't download anything from the start). As such, the whole idea of versions is diminishing.

In the most radical example, Adobe recently announced that they are moving toward a cloud solution with the Creative Suite. Imagine the cheers from the tech comm department when this announcement was made. This means tech writers won't have to support different versions of the Creative Suite going forward. There's just one version -- it lives in the cloud.

5/22 update: Okay, I overstated this a bit. Drupal, Atlassian JIRA, and other platforms do often have multiple versions simultaneously. This is because the latest version often changes dramatically from the previous version, which requires customers to revamp their hooks or other integration details. As a result, the companies can't force all customers to upgrade to the latest version.

Predictability versus natural flow

Some authors like how structured content enforces a specific form and pattern to help content. In a recent exchange on my blog, I compared this model to a straightjacket, while Mark Baker responded that it's more like a tailored dinner jacket.

In a paradigm of "content first," it seems like we should be writing in forms that fit the content. How many people have protested the designer's use of lipsum dolor because it presents dummy content wrapped in a prepackaged structure, which may or may not fit the content?

But in the end, how is this dummy content on a web page mockup different from a help format that prescribes a similar pattern of sections?

At any rate, a simple style guide can help create consistency. You don't have to enforce that consistency with an Document Type Definition (DTD) that prevents anyone from publishing unless they conform to the definition. Let's lighten up, people.

I like to find a natural shape for content rather than restricting myself from the start with a general shape that doesn't always work.

Collaboration requires an easy update process

One thing I have learned recently is that my presence in any company is ultimately temporary. Whether I'm there 2 years or 5 years, one day I'll be gone. And usually I transition from department to department, project to project with a lot more frequency. What happens if I write content in a structured format? Will the product managers and other subject matter experts (SMEs) be able to pick up where I left off to continue authoring?

As far as I can tell, all the help in my Flare files at my previous job remain untouched. I check the help sites every now and then to see if perhaps someone has cracked the code and figured out how to update the help. They haven't. How I wish I'd simply kept the Mediawiki format as before, since it enabled so much better collaboration.

With so much information to know, it's more important to collaborate with other SMEs. I want a format where all users can contribute and take some ownership. The idea of having a process or tool so specialized that only a technical writer with a special skill set can contribute leads to the same single-author paradigm that creates myopic help. I once wrote about this syndrome in Why Help Authoring Tools Will Fade.

In contrast, with a web-based platform, you enable collaboration. You distribute and share content ownership. This point alone about collaboration is worth adopting a web model for authoring and publishing.

Offline authoring is so passé

Perhaps my final qualm with structured authoring is that it seems so offline. The direction of the web seems to be moving toward a more sophisticated in-the-browser experience, where you read and write directly in the browser.

Granted, authoring in a browser's rich text editor kind of sucks, but If I had to compile my blog posts and render them out to an output and then upload the content to a web host every time I wanted to make an update, I wouldn't make too many updates. You shouldn't have to author outside the browser to publish on the web.

Web allows you to harness web technologies

There are many web technologies that empower us to go beyond the old model to achieve so much more. If we're on the web, we can take advantage of these technologies in a much easier way.

For example, let's say you want to take advantage of faceted browsing with search filters that dynamically appear on your search page. Or you want comments below posts. Or an RSS feed so users can subscribe to updates. Or revision histories, or some interactive JavaScript demo, or collapsible sections, or a Twitter stream, or different views of the same content based on tags, categories, dates, etc, or gamification and its points and badges for users as they advanced through levels, or Youtube videos that cycle through a thumbnail gallery. It would be easy to implement all of this on a popular web-based platform.

5/22 update: See Moving Beyond the TOC in Organizing Help Content for more info on the need for faceted browsing.

In contrast, a structured authoring model makes it much more challenging. Trying to continually port your structured content into a web-based platform for publishing seems kind of cumbersome. You can do it, probably, but not without some custom scripts. And then you run into other issues, such as how you overwrite an existing pages without removing its revision history, comments, location, tags, and so on.

The web wasn't built with a model that involves continually deleting and republishing the same pages. Instead, many web platforms are built on a database model of dynamically pulling out the content you want and rendering it in a view. This is still a separation of content from format.

For example, I changed out my entire theme last week (from Canvas to Twentytwelve), and was able to do so in a few hours because the content is stored in a database while the theme files live in a separate file directory. And I didn't need to hire a team of programmers to do it. The web simply makes it easy to publish and distribute information.

It amazes me to think that with all the web advancements, the 25,000 plugins created for WordPress alone, there has yet to be someone who has created a DITA microformat plugin for WordPress, or for Joomla, Drupal, any other web-based CMS (by DITA plugin, I mean a plugin that alters the authoring form, not an import plugin).

Is structured authoring so far from the concerns of any web designer and developer that no one has bothered to code such a plugin? Why don't designers and developers seem to care much about structured content? Invariably structured content seems a concern of the technical writer only. Why is that?

Conclusion

I don't want to come across as being against structured authoring. As I mentioned in the introduction, clearly structured authoring is a trend many companies are following. However, structured authoring has a few challenges before it can live in a web environment. In this post, I mentioned a few trends that I think pose challenges to structured authoring:

- SaaS decreases the requirement to support versioned content.

- Agile makes print publications potentially out of date every two weeks.

- Collaboration requires a form that SMEs can edit, update, and potentially author themselves.

- Mobile works best on a website with responsive design.

- Budget cutbacks force small teams to figure out their own publishing solutions.

- Open source platforms provide a lot of capabilities that we can easily leverage.

- Browser-based editing simplifies the update process, which helps us keep up with rapidly changing information.

I would readily welcome a marriage between structured authoring and the web, and I'm glad to see pioneers like Mark Baker attempt to harmonize the two with his SPFE architecture. Already some DITA vendors are starting to integrate DITA authoring in web environments. See this promising Alfresco integration from Componize.

If DITA and other structured authoring forms want to keep pace with the web, they'll probably follow a similar pattern as Componize. Hopefully at some point, the web CMS will eventually stand alone, with DITA perhaps running the engine but not showing itself to the user. But until then, one almost has to choose sides: structured authoring, or the web?

-------------------

May 17 Update: For some other perspectives, see Sarah O'Keefe's Structured Authoring AND the Web, Mark Baker's Structured Writing FOR the Web, and this summary from Techwhirl: Can Structured Authoring and Web Content Delivery Co-exist?