Single sourcing and duplicate content (search engine optimization)

One of the challenges technical writers face in search engine optimizing their documentation is deliberating between single sourcing and duplicate content. Google tries to return a variety of unique results, rather the same versions. If you have multiple versions of the same content online, Google will likely just rank the version it perceives as best and bury the others.

I'm referring here to single sourcing the same content to multiple online versions, not necessarily a version for different mediums. Suppose you have 9 online guides for "ACME Software": Version 1.0, Version 2.0, Version 3.0. And for each version, you have a Beginner Help, Administrator Help, and a Role-based Help (for managers). Further, you have printed versions (also online) of each of the 9 guides. This means you have 18 guides total.

In every version of the guide, you have a topic called "Setting Preferences." What happens when a user searches for the keywords "setting preferences for ACME help" on Google? Will all versions of the "Setting Preferences" topic appear, given the high degree to which this topic is duplicated?

No, only 2 versions will probably appear -- one web version and one print version. Here's Google's explanation:

Google tries hard to index and show pages with distinct information. This filtering means, for instance, that if your site has a "regular" and "printer" version of each article, and neither of these is blocked with a noindex meta tag, we'll choose one of them to list. In the rare cases in which Google perceives that duplicate content may be shown with intent to manipulate our rankings and deceive our users, we'll also make appropriate adjustments in the indexing and ranking of the sites involved. (See Duplicate content.)

In other words, Google will try its best to only show search results that are unique to the user. If two web pages have pretty much the same content, only one page gets shown. Google does recognize a difference between printed material and online material, so it's likely that both the PDF version of the guide and the specific page will appear.

In sum, if a user wants version 2.0 of the guide for administrators, he or she has a low chance (maybe 12%) of actually getting that result in a Google search.

Why duplicate content gets dropped: Spammy sites

Even though the single sourcing scenario I described isn't addressed in many discussions of duplicate content among SEO experts, the topic of duplicate content is widely discussed. This is because a great many websites scrape content from other sites. For example, I sometimes get pingbacks from spammy sites that have scraped (copied) the content from my RSS feed and posted it on their site in order to rank for specific keywords.

Google doesn't want to penalize the victims of site scraping by demoting both versions of the content. Therefore Google demotes the spammy site while promoting the original site. Its algorithms are usually smart enough to tell the difference, but if it accidentally prioritizes the spammy site, you can report the scraper site through this form.

Canonical tags to the rescue

Duplicate content has also been a problem for mainstream web platforms such as WordPress. Not only is there a version of this post in the single page view, there's also a version on the homepage, date-based archives, category archives, tag archives, and possibly series archives.

To let Google know the right page to prioritize in the search results, you can add the following link in the head of all pages that are the same:

</p>

<p><link rel="canonical" href="http://www.example.com/the-real-page"/><br />

where the-real-page is the canonical page.

The canonical link tag let's Google know that this version of the page is in the canon -- the other versions that duplicate this page are to be ignored.

If you're publishing multiple versions of help material online, consider adding the canonical link tag to the version that you want surfaced in the search results. Adding a canonical link tag will ensure that one page gets priority over other pages. (See rel="canonical" on Google Webmaster Tools Help Center for more information.)

Let's apply the canonical tag to the previous scenario: Which "Setting Preferences" topic should we prioritize as the canonical topic?

One solution might be to add canonical links to the latest version only, and to choose the administrator's guide. In the administrator's guide, we could add a sidebar with links that allow users to access previous versions or other guides.

The problem with this method is that it limits Google to one type of search result only. If you're a manager using version 2.0 instead of 3.0, how can you search for that version of content on Google? You can't. You would be limited to the search results provided within your HTML help output.

Linking instead of duplicating

In an effort to avoid duplicate content, let's explore a different strategy altogether. Instead of duplicating content, try putting one version of the content online and link to the various places where you need it.

For example, you might have different tables of contents that show different arrangements of the material (a Beginner TOC, Administrator TOC, and Manager TOC), but all TOCs that contain the "Setting Preferences" topic would point to the same topic.

With this strategy, you'll quickly realize that you can't have a Beginner TOC appear on the left of Setting Preferences, as well as have the Administrator TOC appear on the left of Setting Preferences, as well as a Manager TOC on the left of Setting Preferences.

And this is the problem with TOCs: they lock you into a fixed navigation based on a pre-defined idea of content order and containers. Further, they make it nearly impossible to deal with duplicate content.

Moving from print to web models

Mark Baker expands on the TOC problem in a comment in a previous post. He encourages us to move from print to web models:

Tom, I think the tech comm's obsession with single sourcing and reuse are an indication that it is still stuck in paper-world thinking. Reuse makes perfect sense in the paper world because a person reading one book has to go to a lot of effort to refer to another book — in some cases it could be days or weeks of effort and considerable expense. Better than to repeat material in each book where it might be required than to reference another book that the reader might have a hard time locating.

On the Web, on the other hand, following a link is instantaneous and costs nothing. It makes far more sense to link to ancillary material than to reuse it inline in multiple places. (Which, of course, relates directly to the discussion in your last post. )

Tech comm should be worrying far less about reuse and far more about effective linking.

Of course, there are still many pubs groups that have to produce some form of off-line media, whether it be paper or captive help systems. As long as they have to keep producing those media, reuse does continue to make sense for them.

The problem with current practice, and with current tools, is that they are optimized for this kind of output and still create output for the Web by taking the individual separate documents generated on the paper/captive help model, with all of their duplicated (reused) content, and simply converting them to HTML. (Which is exactly why, as you observe, many of these tools create output that is not search friendly. In addition, such material is usually link-impoverished, which makes it not browse friendly either.)

What we need are a new generation of Web friendly, Web first, hypertext-oriented tools that can also do reuse for paper/captive help outputs, but which use links rather than repetition in the Web output. In other words, they need to be able to compose entire documentation sets entirely differently for the Web and for print/captive help.

In other words, the table of contents is a very paper-centric model for organizing content. Mark isn't necessarily recommending that we delete the TOC altogether, just remove it as a fixed element to the side of each page.

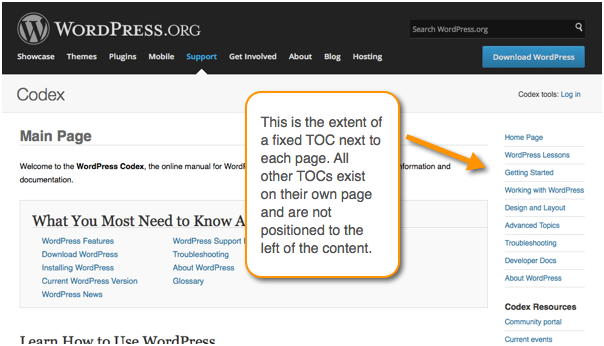

You could still have a page that lists arrangements of links, such as what the WordPress Codex authors do here. But the table of contents doesn't carry through to every single page, except at a high level.

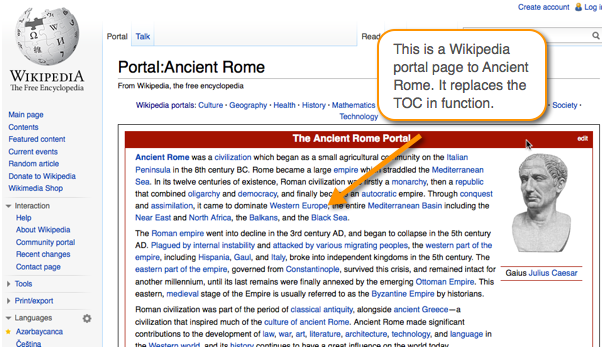

Instead of TOCs, Wikipedia uses a model called portal pages, and you can see an example here for Ancient Rome. The portal page is like a trail map to the content.

The same topic could have numerous different portal pages that show you different entry points through the content. The portal pages might have different focuses based on different business scenarios.

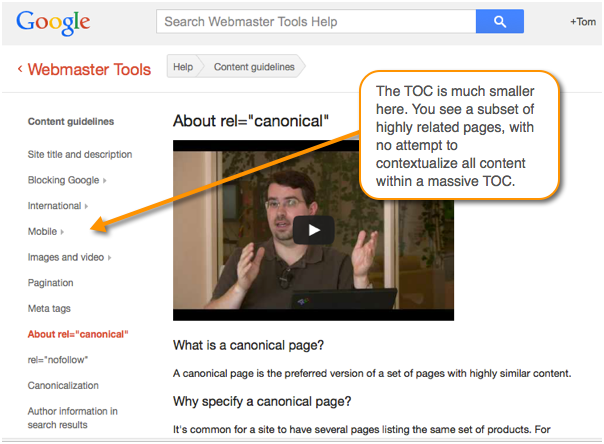

Here are a couple of other minimal TOC approaches. Here's an article from Google Webmaster Tools Help that shows a minimal TOC on the left.

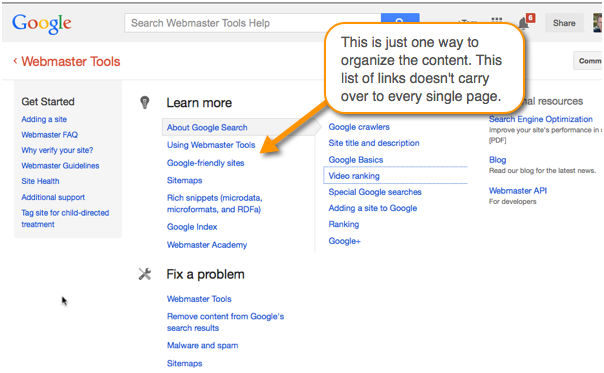

There's a lot more content in their Google Webmaster Tools Help Center. But they aren't trying to force all content into one massive TOC. The same topic might be linked to in the Get Started, Learn More, and Fix a Problem sections.

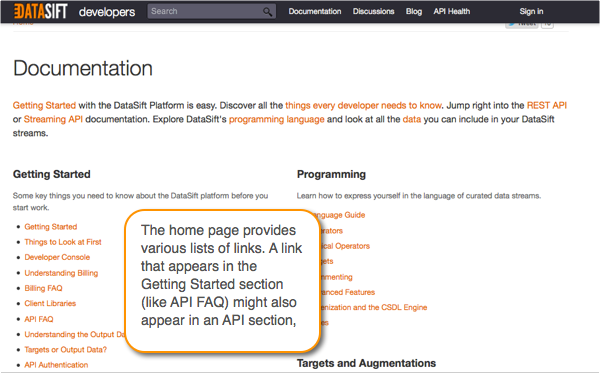

DataSift's help gives another example of a TOC-less organization. The only TOC on the page is a list of pages highly related to the current page you're viewing.

The documentation homepage contains a larger variety of links. These links are not forced through as a TOC sidebar to every page.

Assume readers begin at search, not the TOC

Wouldn't many readers be lost without the fixed TOC on the left side of each page to guide and navigate them through the topics? Mark would say, assume that a user begins at search and searches for content matching specific keywords. Once the user lands on search results, if there are other articles related to the existing article, those articles should be linked within the article. Thus a reader navigates by two main methods:

- Search results

- Internal links within topics

Without question, this kind of organization puts more burden on the page to stand as a  complete whole. As a reader, you don't want to jump back and forth to a portal page each time you want to read another paragraph or list of steps. In this model, pages are longer, more all-encompassing in helping users achieve their goals.

complete whole. As a reader, you don't want to jump back and forth to a portal page each time you want to read another paragraph or list of steps. In this model, pages are longer, more all-encompassing in helping users achieve their goals.

For more details, see Mark Baker's book, Every Page Is Page One. (I highly recommend this book.)

The TOC-less model is most common with wiki architectures such as with Mediawiki sites. The main strength is to free content from one fixed structure. Removing the TOC allows you to create a trail guide (or portal page, or main contents list -- whatever you want to call it) that provides a variety of paths through the same content. This way you can have 9 versions of guides while avoiding duplication of content.