DITA: Why DITA, metadata, working in code and author views, and relationship tables

This is part three of my DITA Journey series of posts. In this article, I explore questions about why I'm working with DITA, metadata, relationship tables, working in Oxygen's code and author views, and more.

Why DITA

A few people have asked me why I started to use DITA. One friend commented that he'd used it a number of years ago and found it both frustrating and restrictive. Others have made similar remarks.

Admittedly, my interest in DITA is more of a curiosity than a true need. Many help authoring tools (HATs) do much of what DITA does. In fact, DITA's inability to produce context-sensitive help is a shortcoming that puts it at a disadvantage to HATs. (See comments for all the people who corrected me on DITA's ability to produce CSH.)

But I have other reasons for using DITA. As I mentioned previously, I am currently publishing on a Drupal web-based platform. It's not one I really recommend for help material. But it has a couple of unique advantages that make it indispensable in my situation. With Drupal, you can restrict access to authenticated users, and you can hook into Drupal's events to trigger other calls.

For example, when someone responds to a forum post, you can hook into the event and make a callback to another service. We integrated our company's gamification features here, so users who respond to posts get points, badges, and rewards, etc. In short, Drupal allows us to provide an example of a gamified community model. When you work for a gamification company, showcasing gamification in any way you can is important.

The problem with many help authoring tools is that their online output can be viewed only within their prepackaged skins. With DITA, you can map the files in a way that allows another system to consume them, such as by embedding metadata in the files (more on metadata in a minute). Building this kind of import mechanism isn't cheap, and it requires programmer skills that I lack. But hopefully that might be something we do in the future.

The other appeal with DITA is the ability to structure content in a universal technical publication format that can be read and parsed by nearly any DITA-aware system. Once I have all my content in DITA, it would be easy to switch systems entirely. An intelligent CMS that can read and process DITA tags can slurp up the content and process it efficiently.

Finally, I have a hope that I can learn DITA and use it for the rest of my career, rather than having to switch from tool to tool. It would be nice if, as an industry, we standardized on a format that was universally recognized. You wouldn't end up with recruiters asking if you know this or that version of a help authoring tool (as Julio Vasquez notes in this post). Your knowledge of the code would be the necessary foundation for any tech comm endeavor. No more worrying about which tool to choose, researching vendors, watching demos, and doing pilots ad infinitum.

Of course, there are many DITA vendors with many different DITA systems and tools, but they are all bound by a common language and technology. And most of these expensive DITA content management systems are unnecessary for small shops anyway. I love the idea that I can create robust, professional grade technical content without spending much money on authoring tools.

Now let me move on to more technical matters with DITA.

Working with metadata

I mentioned the role of metadata in mapping DITA files from one system to another. You add metadata in DITA's prolog element, which comes after the shortdesc element but before the conbody. Here's a sample:

<prolog>

<metadata>

<keywords><keyword>missions</keyword></keywords>

<keywords><keyword>rewards</keyword></keywords>

<othermeta name="Admin Console and APIs" content="API code samples"/>

<othermeta name="Internal Doc Tags" content="API"/>

<othermeta name="node" content="11421"/>

<othermeta name="book" content="JavaScript SDK"/>

<othermeta name="parent item" content="Mission code samples"/>

<othermeta name="placeholder" content="false"/>

<othermeta name="book link title" content="Query for completed missions by creation date"/>

<othermeta name="published" content="true"/>

<othermeta name="weight" content="5"/>

</metadata>

</prolog> When you transform the DITA into an XHTML output, this metadata gets stuffed into the head element of the XHTML file, like this:

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8"/>

<meta name="copyright" content="(C) Copyright 2005"/>

<meta name="DC.rights.owner" content="(C) Copyright 2005"/>

<meta name="DC.Type" content="concept"/>

<meta name="DC.Title" content="Query for completed missions by creation date (JavaScript SDK)"/>

<meta name="abstract" content="You can query for missions by the created_at date field using greater than or less than arguments."/>

<meta name="description" content="You can query for missions by the created_at date field using greater than or less than arguments."/>

<meta name="DC.subject" content="missions, rewards"/>

<meta name="keywords" content="missions, rewards"/>

<meta name="Admin Console and APIs" content="API code samples"/>

<meta name="Internal Doc Tags" content="API"/>

<meta name="node" content="11421"/>

<meta name="book" content="JavaScript SDK"/>

<meta name="parent item" content="Mission code samples"/>

<meta name="placeholder" content="false"/>

<meta name="book link title" content="Query for completed missions by creation date"/>

<meta name="published" content="true"/>

<meta name="weight" content="5"/> >

<meta name="DC.Format" content="XHTML"/>

<meta name="DC.Identifier" content="query_for_missions_by_creation_date"/>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="commonltr.css"/>

<title>Query for completed missions by creation date (JavaScript SDK)</title>

</head> There are some standard metadata elements that are part of the Dublin Core ("DC"), which I didn't specify explicitly in my DITA file. But all my other metadata elements are there. Programmers could leverage this information to programmatically pull DITA content into different parts of a system.

Text versus Author views

One of the things I like about Oxygen is the ability to easily toggle between Text and Author views. One of my worries with DITA is that I'd be knee-deep in code and unable to really see and edit the content itself. This is a valid concern. The whole point of the Markdown syntax (what I was using before) is to have a syntax that is practically invisible. You instead just focus on the content itself. And focusing on the content, being able to edit and shape and manipulate it as a whole, is why I disliked authoring in Drupal so much.

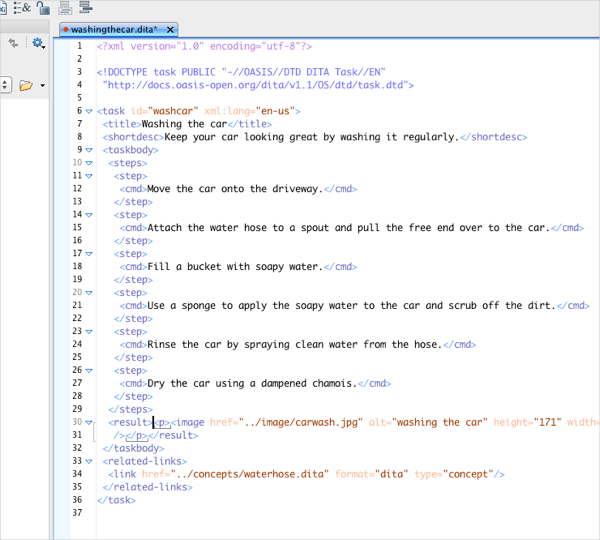

Here are a few screenshots showing different views in Oxygen. Here's the Text view:

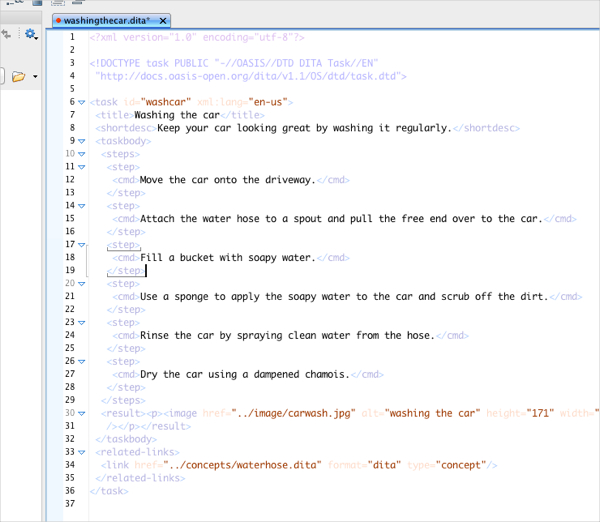

Here's the same Text view but with the tags in transparent mode:

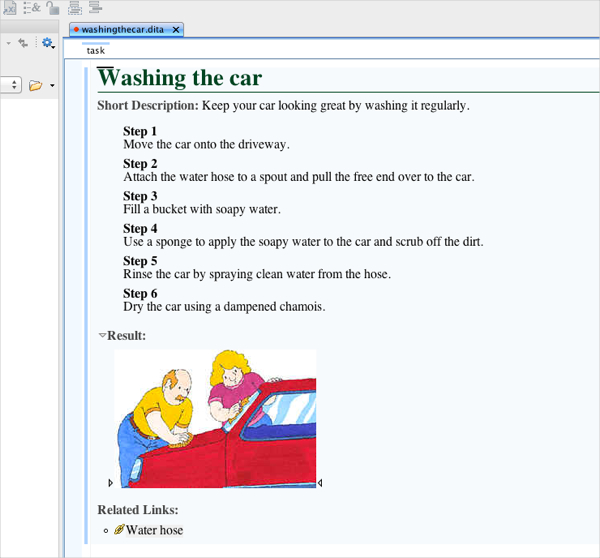

Oxygen offers an Author view, which isn't necessarily WYSIWYG by any means, but it hides the tags and allows you to focus on the content. You can insert elements such as images, new paragraphs, sections, lists, and other elements.

Here's the Author view:

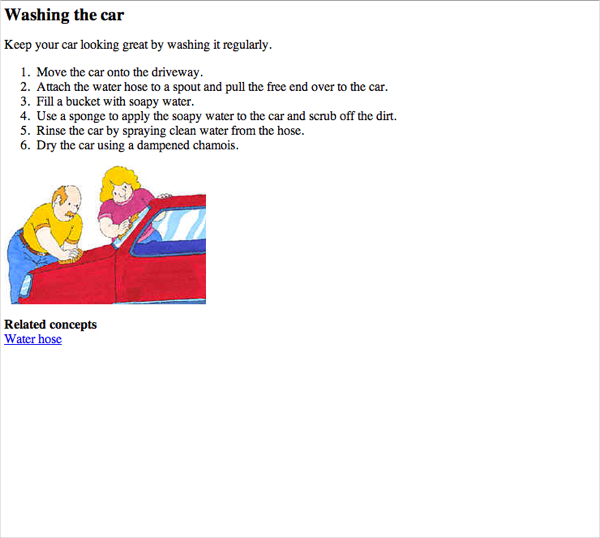

Here's what the content actually looks like when transformed into HTML:

Despite the features in the Author view, whenever I'm structuring the content, I prefer to work in the Text view. The visual interfaces with various DITA tools never seem to clearly tag the content. It's a guessing game as to whether the right text is correctly selected, etc. I can't see what's really going on, and when I peel back the curtain, I usually have to fix a few things. It's just easier to tag the content directly with good old angle brackets.

However, it can be difficult to read the tagged view in a way that allows me to focus just on the content. I can make the tags transparent, which is a big help, but sometimes I just flip over to the Author view to see how it all reads from sentence to sentence, paragraph to paragraph, section to section. The Author view also allows me to see the actual images I've inserted rather than just paths to images.

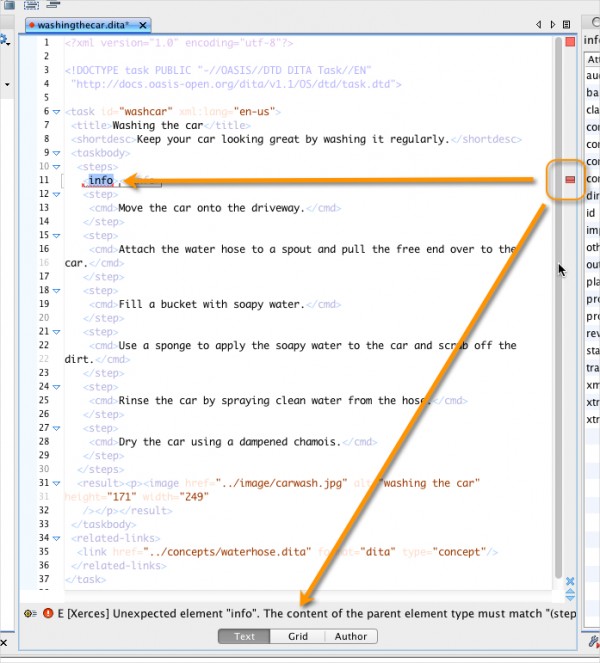

Overall, I can't emphasize how happy I am with the Oxygen XML editor. When I'm working in the tag view, Oxygen validates my content in real-time, showing a little red bar in the scroll area next to invalid content. I can click the red bar and see what's wrong with the structure. In this example, I have an info element outside of a step element.

No doubt DITA gurus wouldn't need that kind of real-time validator as much as novices, but I'm not always sure what tags are allowed where (for example, can you add a note inside stepxmp? How about a p inside context? Does shortdesc go before or after the taskbody tag, and so on.

The more I work with the DITA structure, the more it becomes second nature. But I still consider myself a learner.

Structure is nice to have

When you author in the DITA structure, there are restrictions that guide how you can create and organize content. Some people think these restrictions make DITA authoring a frustrating experience, as my friend mentioned earlier noted. However, I find the DITA structure to be much like a style guide. When you have a style guide, you no longer have to make decisions about things like verb tenses in topic titles, or whether you use stem sentences to start lists, or whether you spell "dropdown" with or without a hyphen. The style guide has already made this decision, so each time you're faced with the scenario, you don't have to expend mental energy deciding what to do.

It's much the same with DITA. When you're writing a task, you know that each step can have various parts. You put the main instructional command inside the cmd tag, and then any additional information, such as a screenshot or extended explanation or note, inside an info tag. If you're showing an example, you put it inside a stepxmp tag.

After a while, authoring falls into a predictable and easy pattern.

That said, there are a few scenarios where I find DITA's structure a little mysterious. Here are several examples:

A step in one of my procedures says,

Insert the following code into the JSON editor:

<code>alert('hello world');</code>I wanted to use a codeblock element to break this code onto its own line (making it a block rather than inline element), but apparently codeblock is only allowed inside info or stepxmp. I could use stepxmp to set it off, but it's not really an example. It's part of the actual command. And I could use codeph or userinput to set it off, but then the code would be inline rather than a block-level element.

Another problem:

I have a topic that contains three parts:

- Brief explanation of the widget.

- Steps to configure the widget.

- Steps to test the widget.

The task element doesn't allow two sets of steps in the same topic, so I'd have to split the testing part into another topic and then merge them through a ditamap using the chunk="to-content" attribute. This seems overkill when the testing section is pretty small (maybe 4 steps and some code samples), and I don't want to have a million little ditamaps all over the place.

In this case, I put the steps to test the widget configuration in the postreq element (which follows the <code>steps</code> elements), formatting the steps with HTML list tags (<ol> and <li>).

Another problem:

The General Task -- I'm not entirely sure whether to use this topic type or not. The general task element allows you to precede a list of steps with sections (which isn't allowed in the strict task type). If you have a topic that merits more explanation than a brief paragraph, and you want to natively combine the concept with the task, this seems to be the element to handle that. You can structure the topic like this:

SECTION A

lorem ipsom dolor

SECTION B

lorem ipsom dolor

SECTION C

lorem ipsom dolor

steps section

1.

2.

3.However, there's not really a way to do this:

SECTION A

lorem ipsom dolor

SECTION B

lorem ipsom dolor

SECTION C

lorem ipsom dolor

HOW TO SECTION D

steps section

1.

2.

3.In the second example, I have a heading for my list of steps. Without the heading, the steps look like substeps for Section C rather than being their own section.

I could add this before the heading:

<section><title>HOW TO SECTION D</title></section>

steps section

1.

2.

3.But the problem now is that the section title is separated from the steps section through its own div tag (as the Open Toolkit renders the tags). While that actually doesn't matter with my output, it seems like I'm breaking the rules somehow.

I'm sure I'll figure out workarounds to these issues, but I describe them here to give a sense of the restrictions or annoyances you can run into when working within a structured authoring model.

Relationship tables

One appeal of DITA is the ability to reduce links between topics to something easier to manage. Already I've begun eliminating a lot of inline links in my content, attributing the inline links to more of an organizational problem than anything else. DITA's Relationship tables offer the ability to more intelligently interrelate and link content. Here's a sample relationship table:

<relrow>

<relcell>

<topicref href="creating_rewards/creating_rewards_overview.dita"/>

</relcell>

<relcell>

<topicref href="creating_rewards/configure_basic_reward_info.dita"/>

<topicref href="creating_rewards/configure_player_criteria.dita"/>

</relcell>

</relrow>You can also use keyrefs in the relationship tables:

<relrow>

<relcell>

<topicref keyref="creating_rewards_overview"/>

</relcell>

<relcell>

<topicref keyref="configure_basic_reward_info"/>

<topicref keyref="configure_player_criteria"/>

</relcell>

</relrow>

</reltable>In general, relationship tables read the links in each row and provide a Related Links section at the bottom of each topic within that row. Topics within each row get links to each other.

You can control how the links relate to each other with more granular attributes, specifying targets and sources and such, but the gist of relationship tables is that you manage your links in one place -- a ditamap file. Readers learn to look at the bottom of the topics for links. If one of your outputs doesn't have a topic, the link is intelligently omitted from the output.

Unfortunately, because I don't have a mechanism to push DITA content into Drupal, relationship tables won't work for me (all the links relationship tables produce are relative). I'm using an interim solution of manually updated keyrefs that point to pre-created Drupal nodes. Since the keyrefs point to the Drupal nodes and not to DITA files, the relationship table logic can't process the relationships.

As a result, I'm using the more manual related-links element, which looks like this:

<related-links>

<link keyref="contests_overview"/>

<link keyref="creating_contests"/>

<link keyref="contests_overview"/>

</related-links>Both on my blog and others, there's been a lot of discussion about the best way to link content, and I'm not going to get into it here. See Mark Baker's recent post about passive linking for an example, or this thread on my previous post about linking strategies with DITA.

Converting content

Finally, let's talk briefly about converting content to DITA. I was at an STC Silicon Valley chapter meeting the other day, talking with someone who uses DITA. The person said she uses SDL and currently had about 10% of their content converted to DITA. The rest remained as legacy Framemaker content, which they weren't planning to convert presumably because the content didn't need much updating.

It's a pain having part of your content in one format (such as in a help authoring tool), and another part of it in DITA. It feels better to have all of your content in the same format.

At first I thought I could quickly convert all my content into DITA using Oxygen. Just paste in the HTML in a new Oxygen HTML document and transform it into something like a DITA concept. The problem is that this conversion is problematic. There is so much to DITA conversion that is more complex, especially converting content into tasks (because tasks have a lot of unique elements not present in HTML).

The most cumbersome part is not so much formatting the content with new tags, but restructuring the content so that it works within the existing DITA structure (such as adding a shortdesc for every topic). If content were perfectly structured (just not tagged) to begin with, converting content would be a mechanical task. The problem is when content itself needs to be edited, rewritten, and otherwise modified while simultaneously putting it into a new structure.

As always, if you have tips or pointers about DITA that you'd like to share, feel free to do so in the comments.