Outside the tech comm tool bubble, there is a wide, wide world

If you hang out in tech comm circles, attend STC meetings and technical writing conferences, and interact on tech writer blogs and forums, you might think the general tool options for professional technical writing goes something like this: You can use a help authoring tool, such as Madcap Flare, Framemaker, or Author-it. You can also structure your content in DITA, using an editor such as OxygenXML. If you're a big corporation, you maybe publish your content on a CMS of some kind, like SDL or Ixiasoft. If you're in a highly collaborative environment, you might use a wiki such as Confluence or Mediawiki. If you're simply unlucky, you may be stuck with Microsoft Word. And that's about it. Of course there are more tool options, but they all do more or less similar things.

In contrast, if you step outside the tech comm tool bubble and interact in API documentation circles, the tool conversation is much different.

Note that when I say API documentation, I mean two things: reference documentation about the classes, functions, methods, etc. for the API. And accompanying developer guides that include getting started information, code samples, and other tutorials on how to actually use the API.

You can generate API reference documentation from comments that developers write in the source code using documentation generators. Documentation generators often work for a specific language. For example, Javadoc is a documentation generator for Java. pydoc is a documentation generator for Python. VSdocman is a documentation generator for C#. Doxygen is a documentation generator for numerous languages, including C++, Java, C#, and more.

Wikipedia has a comprehensive list of documentation generators. Anita Andrews also compiled a good list of documentation generators in her article "What tools do you use to produce API documentation?" Doxygen also has a list of alternative doc tools.

If you look through documentation generators, it seems that most of them stopped development a number of years ago. For example, I was excited to find Doc-o-Matic because it not only seems to handle several languages but also accepts additional files outside of the program source files. Unfortunately, it seems Doc-o-Matic is largely abandoned, their last update occurring in 2009. I emailed the company twice asking if the software is currently being worked on, but I never received a response.

Today the most common documentation generators seem to be Doxygen, Javadoc, and Sphinx. If you do a search on indeed.com for these tools, the results give you a good idea of what people actually use. Many of the keyword results are listed in jobs for engineers rather than technical writers. That's because these are the tech writing tools used by developers. If you ask a developer what DITA or Madcap Flare is, he or she will give you a blank look.

Most developers are not so much interested in content re-use or single source publishing. Instead, developers tag up the API source files with special syntax that Doxygen, Javadoc, or Sphinx documentation generators can read. For example, they might write this before a class:

/** * Provides the blah blah blah for the gizmo. /* @param acme Specifies such and such... @param gadget Provides the value for blah blah... @return A bunch of cool stuff... @throws A huge exception if you misconfigure it...

The documentation generators then parse the code comments and transform them into an HTML output.

If you're coming from a tech writing background and trying to write or edit API documentation that involves documentation generators, you may be wondering what to do with your DITA methodology or your help authoring tool. As you write the developer guide, it will be completely separate from the auto-generated documentation.

Rather than one central output, you'll have a reference guide and a developer guide as separate deliverables. This divided output isn't my first choice, because I think code samples and other tutorials related to a classes, functions, or methods should be more closely coupled with the definition of that class, function, or method. Consolidating things seems a better way to provide one-stop-shopping for information and search.

Not only does consolidating documentation make sense from a content organization point of view, I also find that when the reference doc is generated separately, largely by engineers, I feel less responsible for the content. In contrast, when the content is in my guide, I feel more ownership and responsibility.

If you want to consolidate both the API reference documentation and developer guides, you have several options:

- Use API doc tools exclusively

- Pull API doc into tech comm tools

Option 1: Use API doc tools exclusively

To consolidate your outputs, you could abandon your tech comm tools and use the developer tools exclusively. For example, Doxygen can process Markdown documents (outside the source code) as well as source documents. Your output can then be one integrated whole.

Markdown is a lightweight markup, kind of like wiki syntax. You can learn it in about an hour. However, Markdown is primitive and doesn't allow for content re-use, variables, conrefs, or other more sophisticated publishing.

If you're publishing with Sphinx, you must format everything using rST, which is similar to Markdown but more robust. You can also bring your Doxygen XML output into Sphinx through Breathe.

Note that you cannot simply export your DITA map's XHTML output and include it in a source directory that Doxygen can consume. Doxygen and many other developer tools, such as Slate, API Blueprint, Nanoc, Github, Docco, Jekyll, or Pico CMS, specifically process Markdown content. (You can take all that fancy DITA tagging that you did with your high precision XML editor and replace it with the equivalent of crayon drawn on cardboard.)

Markdown keeps things really simple. And simplicity is in style. Just look at all the fixed gear bikes. The minimalist websites. The simple apps so proud of their non-cluttered interfaces. Keeping doc authoring simple follows the same pattern. For developers with much more pressing concerns (i.e., coding an API), worrying about complex XML tagging is beyond their interest. Hence, Markdown. And the tools they build to process API doc work harmoniously with their chosen doc authoring method.

Although documentation generators are pretty common for dev shops with Java or C++ code bases, if you have a REST API, which is essentially a list of URLs and configuration options that return data in JSON format, then documentation generators are much less common.

With REST APIs, some people use tools like Slate because they're imitating the Stripe API (which everyone seems to hold up as an example of perfect API doc). Others roll their own platform, such as Twitter does with a custom Drupal site. jQuery's API doc site actually uses WordPress.

There are some documentation generators for REST such as Swagger and RAML, but you won't find any kind of common publishing strategy akin to the Javadocs and Doxygen tools in the REST API world.

Part of the diversity of REST API docs is driven by the increasing ease to build websites (Bootstrap, jQuery plugins, node.js, and many other packages make it easy to get the functionality and style you want) and the higher frequency of front-end development skills. Why settle for a static, boring format like Javadocs when you can instead brand your content, make it interactive, include jQuery effects such as tabs, collapsible sections, dynamic tables — in short, when you can build a modern looking website?

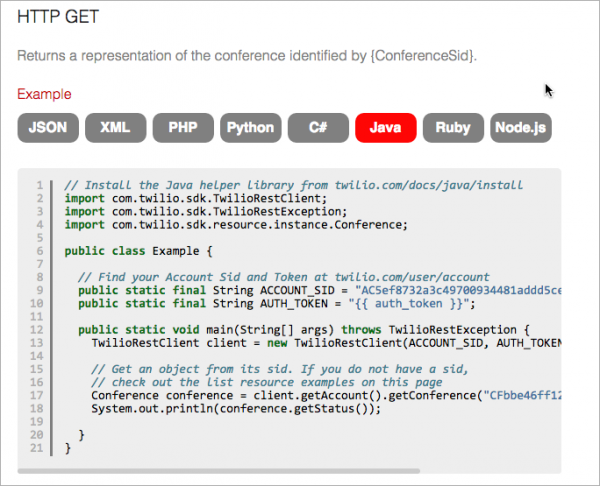

Additionally, many APIs have specific challenges that documentation generators can't handle. You probably want to show how your API works with a handful of languages, such as PHP, Ruby, HTML, JavaScript, Python, C++, and more. Many API doc sites provide tabs that users can click through to view the programming language they want. For example, see how Twilio does it.

Many API doc sites also incorporate infinite scrolling. Clicking is so passé nowadays. Rather than click from topic to topic, why not just auto-load the next topic as you scroll down? Here's an example that uses Slate to facilitate auto-loading with scroll. And another example from the Intercom API.

Option 2: Pull API doc into tech comm tools

Let's say you want to stick with your tech comm toolset, but you want to incorporate the API reference information from the source files. What are your options for this strategy? You can sort of do it through DITA.

For Java, Docfacto has a DITA doclet that will parse correctly tagged comments in Java source files and create DITA topics out of them. However, this is much easier said than done. As I've explored this doclet, although it does pull the content into DITA, I have a host of challenges to resolve in figuring out why some files triggered errors or didn't resolve, as well as styling the formatting so that it looks on par with Javadoc or Doxygen's output, and spending time with other troubleshooting.

For C++, you can use this DITA plugin to convert code comments in C++ to DITA. I haven't explored this plugin yet, so I can't comment on how well it works.

For C# and other languages, you're on your own. You can probably hire an XML developer to create the kind of transform you need to pull source code comments into DITA.

However, note that just pulling the reference content into DITA doesn't magically solve problems. You will need to regularly reimport the content as developers compile new builds of the code. And no doubt you'll want to integrate into the developer's build process as well, so you'll need to install and configure Maven with your IDE (e.g., Eclipse) to get their latest builds and become familiar with the version control system, such as Git or Mercurial.

The big questions

When I look at the API landscape of tools, there are several main questions I find hard to answer:

1. Is the tech comm toolset, particularly DITA, too incompatible to integrate with these developer tools, which prefer markdown and rST instead of HTML and XML?

2. Are documentation generators generally on the decline given the rise in REST APIs and the ease of publishing on custom web platforms?

3. What is the best way to integrate API reference documentation with developer guides while also keeping needed documentation in the code source?

One organization that has been particularly helpful in paving the way with developer documentation is ReadtheDocs. They have a toolset built (mostly on Sphinx) to facilitate developer doc. You can view various documentation projects on Readthedocs.org.

What I'm currently doing

Right now I'm still using DITA and trying to make some of the DITA transform plugins work to pull in those Java and C++ source comments into DITA topics. But my guess is that in the long-term, this is a developer's landscape, and trying to use tech comm tools to document APIs might be as fruitful as a developer trying to use Doxygen or Sphinx to do a tech comm GUI documentation job.

Then again, maybe tech comm publishing tools, with the ability to add attributes and conditional processing, can help elevate developer doc to a new level.

I'm not entirely certain on the right direction. For now, there are a lot of options, very little in terms of standards, and major challenges to solve. Despite all these problems, it's precisely these difficulties that make API documentation the most interesting space to be in right now.

(By the way, if you're in the SF Bay area, I'm speaking to the San Francisco chapter on the topic of API documentation on October 15. You can see more details here.)

Additional reading

For more thoughts on this topic, see Code Skimming by Daniel Beck.