XML and the web: drifting farther apart?

In my previous post in this series, I explored how the web empowers everyday people as technical writers. I'll return to this idea in a major way, but first I want to note some other trends that will plug in to this ongoing discussion on innovation. In this post, I want to dig a bit into XML and the web.

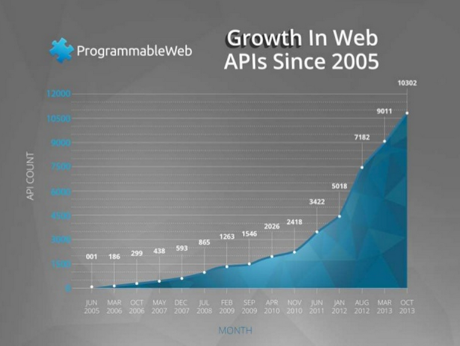

One major trend in communication technologies is REST APIs. According to Programmableweb.com, which maintains an active directly of REST APIs, there are approximately 12,000 open web APIs. Their growth over the past decade has been exponential:

A REST API basically allows client-server interactions for information. The client submits a request to the server and gets back information. For example, if you want to get a gallery of photos from Flickr, you use a particular endpoint (such as flickr.galleries.getPhotos/{gallery_id}), and you get back information for the gallery.

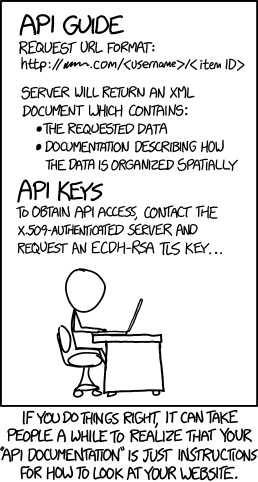

REST APIs exchange information through the same HTTP protocol as websites. On the web, you get to a site by passing in a request in your browser URL (such as https://idratherbewriting.com). This gets the resources from the server assigned to this endpoint. This comic from XKCD is spot on:

I've covered REST APIs in detail on my blog before. The point I want to highlight here is the format of the information returned. For the most part, information returned from REST APIs is in JSON format. JSON format is a simple key-value pair format, such as the following:

"name": "Tom"

"role": "Blogger"

"age": "39"

"status": "Awesome"

}

JSON is really easy for web designers to parse. To get the name from this object (supposing the object's name was data), you use dot notation such as this:

data.nameJSON stands for JavaScript object notation. It fits in well with JavaScript, which is one of the most common languages used on the web (right next to HTML and CSS).

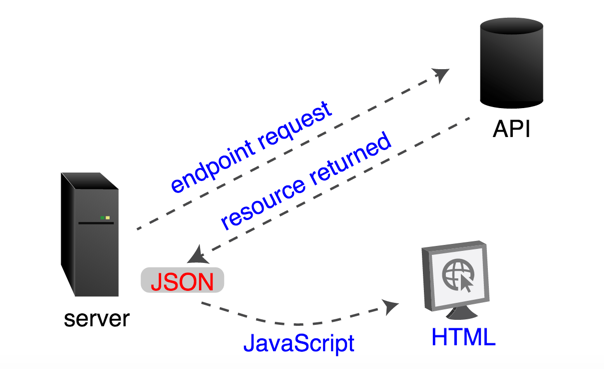

Here's a diagram depicting the flow of information from servers via REST APIs:

Usually the response from the server is provided in JSON format, which makes it easy for web designers to grab with JavaScript and integrate on a website.

About 10 years ago, rather than JSON, a common information format was XML. You can still get XML-formatted responses by many APIs (for example, Flickr lets you choose either XML or JSON), but many APIs stopped supporting XML as a response format. Without a doubt, JSON is now most common (and probably the most preferred) data response format. XML is dying out as a format for REST API responses.

If you don't believe me, do some searches for, "Is XML dead?" Most of the sites you'll find aren't talking about XML as a document format for single sourcing content. Instead, they're talking about XML as the data exchange format for computers, that is, the way information is structured when it's returned from servers to requesting clients.

Why is XML for web services exchanges on the way out? One reason is that XML is too verbose (and hence slow). There are too many tags, which take up too many characters and therefore slow the response down. JSON is much more lightweight and fast, which is essential if you have a SaaS company with a REST API.

When I worked at Badgeville, returning gamification responses (like the number of points a user has) in 50 milliseconds or less was critical. Lengthy responses will cause client sites to load and perform slowly. Slow responding APIs just don't work on the web when your site's loading time depends on the API's response.

As another example, with advertising technology, you have to return information in about 20 milliseconds to enable real-time bidding for ad slots. With digital advertising, all kinds of things happen in supersonic speed to determine what ads the site shows you. If your API response is slow, real-time bidding gets skipped.

Some people say XML is not that verbose, and the extra speed from JSON is minimal. Others simply say that JSON better fits the JavaScript paradigm of the web. There are probably countless other reasons and arguments between these two data exchange formats, but whatever the reason, JSON is certainly trending towards the norm when it comes to REST API responses, not XML.

Here's an excerpt from a post by James Clark, one of the leaders behind XML and actually the person who came up with the name XML in the first place. In a seminal blog post called XML vs the Web, James writes:

"There's a bigger point that I want to make here, and it's about the relationship between XML and the Web. When we started out doing XML, a big part of the vision was about bridging the gap from the SGML world (complex, sophisticated, partly academic, partly big enterprise) to the Web, about making the value that we saw in SGML accessible to a broader audience by cutting out all the cruft. In the beginning XML did succeed in this respect. But this vision seems to have been lost sight of over time to the point where there's a gulf between the XML community and the broader Web developer community; all the stuff that's been piled on top of XML, together with the huge advances in the Web world in HTML5, JSON and JavaScript, have combined to make XML be perceived as an overly complex, enterprisey technology, which doesn't bring any value to the average Web developer.

"This is not a good thing for either community (and it's why part of my reaction to JSON is "Sigh"). XML misses out by not having the innovation, enthusiasm and traction that the Web developer community brings with it, and the Web developer community misses out by not being able to take advantage of the powerful and convenient technologies that have been built on top of XML over the last decade.

"So what's the way forward? I think the Web community has spoken, and it's clear that what it wants is HTML5, JavaScript and JSON. XML isn't going away but I see it being less and less a Web technology; it won't be something that you send over the wire on the public Web, but just one of many technologies that are used on the server to manage and generate what you do send over the wire."

Another great post on XML versus the web is this Web Services: JSON vs. XML post. Here are a couple of key highlights:

"When you replace your front-end service with a particular technology, it tends to affect the back-end. At our company, we've started to use JSON-like objects for not only our Web Services, but for all of our system data."

and

"Perhaps XML experts are trapped by the innovators dilemma, not seeing the struggles that the rest of us face when building Web Services as XML non-experts. XML tends to be surrounded by complicated tool-chains and processing rules, which probably seem simple if you've been heavily involved in XML world for years.

"However, the world moves on and when young programmers compare XML and JSON side-by-side, they almost inevitably gravitate towards JSON. JSON is easier for those yearning for a simple data serialization format that works seamlessly with the Web. JSON is certainly scratching an itch that many of us Web developer types have and for that we can be thankful. XML will continue to survive for a very long time, it is good in its problem domain. However, we should not forget that XML tried to play in the Web Services game and it fell short ..."

See also Web Principles: XML Lead Explains Its Demise on the Web, by David Hammond.

Implications for tech writers

You may think, well, what does this have to do with me? I'm a technical writer using XML to structure my information for maximum re-use. I'm not delivering REST API responses. The trend away from XML for web services has nothing to do with using XML in documentation scenarios.

Actually, the data exchange format that programmers use does matter to technical writers. JSON is becoming the de facto data exchange format for client-server interactions, which means that the technology stack web developers are using is based on parsing JSON, not necessarily XML. Most designers and developers know how to process JSON responses using JavaScript. They know how to pull information out and display it. If you give them XML, many developers and designers may draw a blank or refuse to work with it.

One tech writer I know says when he asked his developers if they could process XML, they looked at him as if he had tried to give them a bag of wet socks.

Another tech writer I know worked with a UX team to create a doc portal. He was using DITA. In order to feed the content to the doc portal system, which was built on Node JS, the tech writer had to write his own XSLT script to convert the DITA XML into JSON, because the web team needed it in JSON.

With JavaScript and jQuery included in nearly every front-end website, the web developer's stack (their foundation of technical tools) is built around processing JSON, not XML. Most web devs I've met want to work with JSON, not XML, because their whole tooling is around JavaScript and JSON.

So what...?

So what?, you say. My XML is processed by OxygenXML. I don't even interact with this web developer....

But can you see the diverging paths here? Web developers are building tools, web platforms, and other plugins that process JSON, HTML5, JavaScript, and CSS, because this is the language of the web. XML is dying out as a web platform language used for building the front-end of websites. Since web developers are the tool builders, by using an XML solution that relies on a different technology stack (XSLT, Ant, XPath, XQuery), technical writers are veering farther and farther away from the web platform stack and trends.

I'm not saying web devs can't work with XML or don't know how to -- I'm saying the trend is moving away from XML as a common language among web developers and designers. Since technical writers publish help material in web contexts, this trend matters to us. Without a common familiarity with the XML stack among web designers and developers, XML is becoming more and more of a stranger to web platforms.

Reliance on vendor solutions

These trends away from XML among web developers may not matter if you're using a tool built by a tech comm vendor. You may be happy with all the functionality you need from Tool X. That's great. But I think technical writers using XML solutions will become more reliant on vendors for their tools than on open source web technologies. Many of these vendor solutions are robust and definitely address the needs of large organizations doing both translation and multi-channel publishing.

But did you know that if you used web platform technologies (HTML, CSS, JavaScript, jQuery, JSON), you could probably leverage a great many open source tools for free, doing the publishing yourself? Alternatively, you could join forces with your own company's UX people in forging custom solutions.

Of course, free and open source tools are often fraught with steep learning curves and error messages, but many of these tools are solid foundational tools. For example, being able to use HTML5 tags to embed videos, jQuery to incorporate interactivity, CSS3 to style gradients or animations, and specialized JavaScript libraries for other needed functionality can help you publish your content on the web in unimagined ways. You'll be using a platform built for the web, built and maintained by current web developers and designers. As the advancements in web technology increase, you'll ride right along with all that innovation.

Reliance on tool vendors

The more technical writers rely on XML, the more reliant they will become to vendors, consultants, and other specialists. Despite all the hype about DITA having robust publishing capability, it's still difficult to transform content from the DITA structure to a modern web format. You usually have to build a stylesheet using XSLT, which is not a programming language that is easy or familiar to most people. Hence, most solutions for web transformations aren't concocted by individual technical writers but rather purchased from vendors who employ engineers to build these solutions.

Some tools like OxygenXML's webhelp plugin work well, as does XMetaL's solution, but both solutions give you a tripane help output with little ability to customize the layout or incorporate your own JavaScript or styling. You can change a few things like colors and font sizes, but you can't, for example, skin the entire site with the same layout as your company site, or implement different sidebars for different pages, or switch layouts entirely and use tags to link pages (such as when displaying knowledgebase articles). You're pretty much stuck with the massive TOC model (one TOC for everything), which is a design pattern that doesn't work when the TOC gets large.

There are some innovative DITA vendors, such as Componize, Fluid Topics by Antidot, Suiteshare, IXIASOFT, and easyDITA, but most of these platforms are sophisticated publishing tools that are costly (approximately $30-60k annually), and you get locked into reliance on the vendor for updates and innovation. If you want to make an adjustment to meet a different documentation situation, you really can't pivot quickly making your own hacks. And probably the vendor's system will be separate and siloed from the web platform your company's UX team is using.

There is no way that a handful of XML vendors are going to keep pace with the hundreds of thousands of web developers and web designers who are rapidly coding new technology on the web and making much of it available for free.

Trends toward content APIs

If you're not yet convinced that XML might not be the best route for web publishing, consider this trend: JSON APIs. I wrote a post the other week showing how to convert the content on your website into a JSON API. One of the ideas of healthcare.gov is for the site to be a hub from which other sites in the healthcare ecosystem can pull and embed content using a similar technique.

Consider a world where the website itself is no longer where people go to get information. Instead, the information from the website is pulled into applications, error messages, alerts, blogs, emails sent to customers, and more -- all pulling from your help material that is a JSON API. Rather than pulling users to the help, you push help to the users.

It's an aggressive idea, but one that -- in a world of ubiquitous APIs talking to each other -- might really be a reality. And how will web designers pull in this help content from your API? I bet that they will expect and demand a JSON format.

Feedback welcome

I'm making some pretty radical arguments in this post. And if there's one subject where people are extremely passionate, it's tools. Let me know if you think I'm on the right track here or if you think I'm wandering around in the far craters of the moon.