Eight reasons why documentation fails for users, and what to do about it

Background

Lately I’ve been trying to learn Android, and I’ve been following various tutorials. Finding a good Android tutorial that walks me through the basics in a friendly, easy-to-follow way is difficult, especially since I’m not the target audience (i.e., a developer) of most Android documentation.

It has made me realize that good documentation is rare. If you find a tutorial that works well for you, it is probably the result of a lot of careful testing and refinement of the instructions.

Why is documentation so frequently poor? Good documentation can be particularly hard to write for the following reasons.

Reason 1: Operating system mismatches

Tech writers and users sometimes have different operating systems. What works on a Mac might not work on Windows. Or what works on Windows 7 might work the same on Windows 10. Throw in Linux too, and you’ve got some variety to consider. Unless you try multiple operating systems while writing the docs, you might not realize the differences.

Solution: Test documentation that is operating-system-dependent on on Windows, Mac, and Linux platforms.

Reason 2: Version mismatches and product evolution

Technical writers usually document the latest version of the software, and when they publish, they’re done (at least for a while). They don’t always get to stick around to update the published documentation through the life of the product.

However, products don’t reach end of life on their first release but rather continue to be updated incrementally, especially if the software developers follow agile methods. Unless tech writers are constantly following each update and updating all the docs to match, doc eventually drifts apart with each new version and eventually becomes less and less accurate.

The documentation that was written for version 1.0 gets slightly out of date when 1.1 is released, and more out of date as the versions increment. Additionally, users may not be using the latest version of the product.

The longer you’re at an organization, the more you get pulled in different directions, since you build up a larger base of documentation you’ve written for various products. Eventually you have to cut ties with your previous projects to stay afloat with the workload.

Solution: Note the versions you’re using to create the documentation, and provide links corresponding to different versions of the documentation. Also stay attuned to product developments for the doc you write. If you notice releases without doc updates, log a bug about it.

Reason 3: Differing technical abilities

Technical abilities differ from person to person. If you’re a novice trying to follow an Android tutorial, your questions and needs will vary from an iOS developer transitioning to Android development, or from a Java or C++ programmer beginning Android development. The tech writer usually writes for his or her own level and questions, and assumes users will be similar to him or herself, but this is rarely the case.

Solution: Test your docs with your target audience.

Reason 4: Business scenarios differ

Tech writers usually create documentation following the intended business scenarios and designs of the application, but sometimes users have completely different scenarios. For example, a person following an Android tutorial may want to create a TV app instead of a smartphone app. As a technical writer, you don’t always know the variety of business scenarios and needs users will have.

Solution: Provide feedback channels so you can learn when your doc falls short of the users’ needs, and then evolve the doc to meet those needs.

Reason 5: Support channels are separated from doc

It would help tech writers if users could give updates when they run across out-of-date information, but often the support channels are completely separated from documentation. In fact, knowledge bases themselves are usually siloed from doc.

Tech writers usually don’t want to deal with support, and they know if they put a contact form on the doc pages, they’ll be inundated with support requests that speak more to product bugs and feature shortcomings than with doc-specific issues. Support people also prefer to keep support threads in their own domain. The result is that tech writers become disconnected with their users and cut themselves off from critical feedback channels. (I will return to this topic near the end of this post.)

Solution: Provide feedback mechanisms in the doc. Also monitor support channels.

Reason 6: Products have their own terminology.

Products present a new language users must learn. Learning Android, I’ve had to learn what APK, ADB, AVD, activity, intent, fragment, context, res, and many terms mean. When you learn a new product, you often learn a new language. Without a clear glossary, it can be difficult for people to understand what the doc is saying.

Of course tech writers have to make assumptions about users’ technical ability, and they can’t always explain terms with each usage. Additionally, the longer tech writers are immersed in an environment, the more blind they become to the jargon and specialized terms used. Even so, tech writers must remember that users might not be familiar with each of the terms in the documentation. It might be the equivalent of throwing in words from another lengua here and there.

Solution: Include a comprehensive glossary that captures all product-specific terms and jargon.

Reason 7: Tutorials don’t provide an end-to-end process

Help topics are often focused on a specific, individual task that is assumed to be done within a larger process. Because there are a number of ways users can use a product, it only makes sense to create small topics. However, tech writers often assume that users know how each task fits into a larger workflow. That assumption is often unfounded. Users need to see the larger picture of how to use a product in an end-to-end scenario.

Solution: Show larger workflow maps that link to various task details in end-to-end processes.

Reason 8: Steps are simply inaccurate

This happens often – as a user you try following the steps for a process, but the documentation misses a step or otherwise fails. You get to step 4 and don’t get the result you need to proceed to step 5, so you become stuck. This has happened to me with a number of Android tutorials.

For example, in Google’s tutorial Building Your First App, step 6 says to select a Blank Activity. However, only an Empty Activity is available. This may seem like a simple name change, except that you realize in step 8 that the file app/src/main/res/layout/content_my.xml isn’t created when you build the app. Either I somehow missed the “Blank Activity” earlier, or the product evolved, or I have some other version.

This example is a consequence of a number of issues – a mismatch of versions, a failure to update the docs, and lack of feedback channels for users to notify tech writers of needed updates. In many cases, the steps are simply inaccurate and lack the kind of meticulous review that would have made them easier to follow.

Solution: Triple-check the steps of your documentation.

Larger solution: See doc as iterative, with each user a tester

Of course you can improve docs by following all the solutions I’ve mentioned here (testing on different plaforms, being careful to note the version and date, doing user-testing, triple-checking steps, and so on). But it’s not usually possible to do all of this within the timeframe you’re given to write the documentation. What can you do?

I think the answer is simple. Change your mindset about when documentation is “done.” Instead of seeing docs as complete/final at launch, see doc as an iterative process that gets better each time someone uses the doc.

Ideally, I’d like to integrate some feedback mechanism (such as Disqus or Annotator) directly into my docs. For example, had there been a simple feedback mechanism in the Google Android tutorial I mentioned, I would have commented on the word “Blank” in the Google tutorial. This could have potentially improved the accuracy of the tutorial.

Tech writers can’t be expected to catch everything, but through continual feedback from users, you can refine and improve docs. If we can learn to see docs as an iterative process that get better each time someone uses them, this is surely the key to developing great docs.

Having numerous people test your docs in real business scenarios, with different operating systems and environments, would lead to better and better docs each time. But if you can’t capitalize on that real-world testing by capturing user feedback, it all goes to waste. The user gets frustrated because he or she can’t follow a step, and there’s no way to let the tech writer know there’s an issue.

Comment forms at the bottom of articles are a good idea, but allowing users to comment on help is often a controversial practice that writers disagree with.

Learning from Atlassian

About a year ago, Atlassian, known for their interactive software, announced that they were closing comments on documentation. There are more than 70 comments on this blog post, with many people shocked and upset about this move. It seemed to run counter to Atlassian’s core principles. Here are the reasons Atlassian’s tech writers gave for closing comments:

- Committing to moderating page comments creates two huge problems: an ever-increasing amount of comments to moderate and, as a result, proportional overhead on the team. For a company of our size, it just doesn’t scale.

- Only about 20% of comments are contextual. The rest are various types of requests such as support, new features, and general product inquiries. We need to promote better wayfinding from the documentation to the other, more suitable Atlassian channels, and use our limited time in the most efficient way possible. We’ll still listen to and help our customers, we’re just shifting the arena.

- Comments languish unanswered if the IX team doesn’t have bandwidth to review them. Today, the most responsive doc space only achieves between a 60-80% response rate, with most spaces below 40%. That’s an unacceptable user experience.

- There’s no quick or easy mechanism to archive outdated comments, meaning new readers often encounter outdated answers and workarounds in the comments.

- We classed a trial of a ‘no-comments space’ (JIRA Service Desk) as successful. The trial ran for nearly a year and responses from our customer-facing teams have been positive.

At first I thought, wrong move Atlassian, you just disconnected yourself from user feedback, which is what helps make your docs better. Couldn’t you just put a link before the comment form that takes people to a feature wish list instead of closing down all comments because only 20% are contextual?

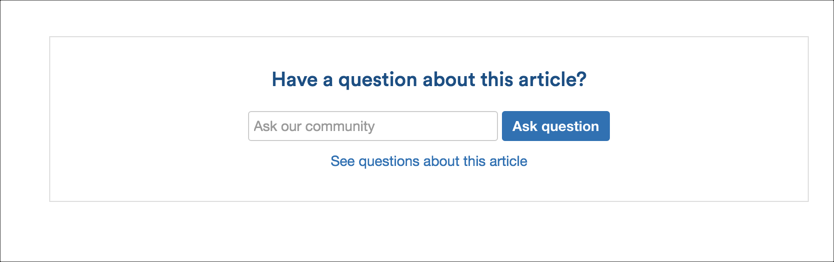

But now I see that Atlassian has neatly added a link from each help topic into their Atlassian Answers tool. I kind of like their new approach.

Let’s say you’re viewing a topic (such as Supported platforms) and you say, wait, I have a question. To interact with Atlassian, you click the link at the bottom of the article, and it takes you to this Atlassian Answers forum. There you can see all questions about the specific article.

Their Answers tool allows upvoting and auto-sorts the most upvoted questions to the top. This saves people from the hassle of having to scan down, in a linear fashion, a long wall of comments, hoping someone has asked and answered a particular question. Additionally, it groups related comment threads together.

Additionally, the forum software allows support engineers to more easily interact with incoming questions. This approach also keeps the size of topics down in the help content. No one likes to load a web page and see the cursor on the right shrink way up at the top because the page scrolls for ten years before you get to the end.

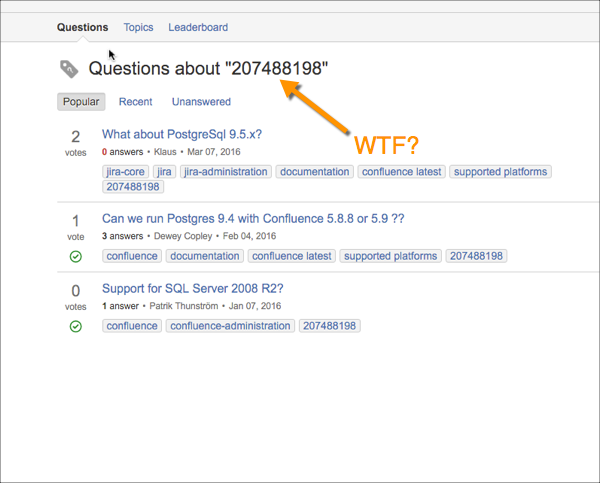

However, their Answers page is orphaned from the original topic, and the questions don’t necessarily make sense without the context of the topic. For example, if you were browsing Answers for your question, the title looks like this:

The answer thread makes no sense without the context of the “Supported Platforms” topic. There’s not even a link back to the topic!

Overall, do I think it’s a good idea? The idea is headed in the right direction, but the implementation could be improved. Given the volume of questions and expected interaction, putting these conversations into a more robust interactive tool can likely increase the response rate. The downside is lost SEO and a somewhat fragmented experience between the two systems. It’s usually better for SEO to keep all content related to a specific topic on the same page, but as Atlassian said, “only about 20% of comments are contextual” anyway.

Conclusion

Writing good documentation takes a lot of time, which tech writers don’t always have. But even if you have to publish minimal documentation at release and keep building on it with subsequent releases, you should do it. Few of us have time to write the kind of quality documentation that covers all the solutions listed above at release time, but the fallacy is that once released, we think we’re done and move on to other projects. This shouldn’t be the mindset. Release should be a kind of “day 1” of the documentation. After the doc release, you iterate and keep improving through continual feedback.