Crowdsourcing docs with docs-as-code tools -- same result as with wikis?

Taking the big step

A couple of weeks ago, I thought I was taking a big step forward by putting my docs on Github. I’d already been using an internal Git repo for the past year, so moving from internal Git to external Github posed no major technical challenges. I hoped the Github repo would enable other devs to contribute pull requests on my docs.

Here’s what my docs look like with the Edit on Github button:

When I announced the new Github integration to my project team, the project manager responded enthusiastically about the potential for “crowdsourcing docs.”

The term “crowdsource” hadn’t been in my mind when putting my docs on GitHub, but I nevertheless welcomed the idea.

It seemed I was well on my way to setting up a massive collaboration engine for documentation. I expected developers to immediately start logging issues, submitting pull requests, and more. But even after a couple of weeks, almost no one made an edit, logged an issue, or contributed any pull requests. (Well, except one mysterious person, who created a small PR but then closed it.)

Two weeks is hardly the blink of an eye, and one can’t expect much, especially without promoting and educating users about it. Still, I hoped for a bit more.

I decided to ask the gurus on WTD Slack how they got developers to contribute edits.

Eric Holscher said I need to build up a culture that cares about documentation, and then encourage developers to help.

Anne Gentle said that developers are more likely to contribute to docs when the docs co-exist in the same repos as the code.

I understand that getting developers to contribute to docs is not a change that happens overnight. Culture is always hard to transition.

Putting docs into the same repo as the code might be helpful, but not all docs have corresponding code repos. Additionally, for docs that do have corresponding repos, devs may want to release quarterly (after some QA and verification). In contrast, I want to make doc updates as needed, on the fly.

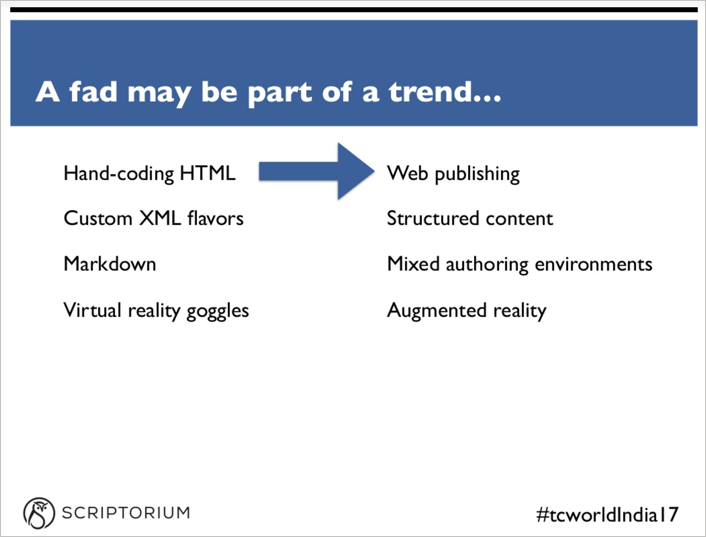

As I was browsing around on some tech comm blogs, I ran across this slide deck from Sarah O’Keefe about her keynote at tcworld India.

Although I don’t have more details about this part of her presentation, the word “fad” got me thinking. Is docs as code a fad? How exactly is the docs-as-code trend different from the wiki trend, which peaked about eight years ago and then floundered?

Rewind – what exactly happened to the wiki trend?

Let’s turn back the clock a bit. About 8 years ago, many people in tech comm were excited about wikis. Why? Wikis allowed anyone to contribute to a body of information, without knowledge of anything more than a simple wiki syntax.

Wikis decentralized docs by enabling push-button collaboration and publishing. Sites like Wikipedia showed us the power of collaboration on a massive scale, and wiki platforms took off.

In My Journey To and From Wikis: Why I Adopted Wikis, Why I Veered Away, and a New Model, I wrote about why I embraced wikis. I embraced wikis because I alone didn’t have the needed perspective to address all the information needs that users would have. I wanted to tap into the users’ insights and knowledge to complete the gaps in my docs. I wrote:

When the community owns the content, community members can also keep content up to date when the original author flounders. Many times the original author isn’t aware of all the places that content is out of date. As community members use the documentation, they often find places that need updating. Because the content is on a wiki, they can quickly and easily make these updates.

Additionally, I wanted to iterate continuously on the docs. Wikis removed the need to build, publish, and deploy content. It all happened magically in the browser when you hit save.

I also noticed that every interesting site online had a massive community driving it:

The potential reward in collaborating with the masses is an idea that shouldn’t be underestimated. Almost everything interesting happening on the web comes about through community. Think of any well-known site. Its innovation isn’t the technical features of the platform but rather the community.

During the height of wikis, I had my docs on Mediawiki and also wrangled the efforts of a large volunteer community. I worked for a non-profit in Utah at the time, and many people wanted to help out. Although docs were on a wiki and editable by anyone, we primarily tried to crowdsource our blog. We had dozens of volunteers who indicated they wanted to write, and I started assigning articles on various topics to them.

To manage 60+ different non-specialized volunteer writers, I used a lot of index cards pinned up into various quadrants on my cube walls. I invited volunteers to tackle specific subjects they had some knowledge about, and then helped connect them with the right info to write it.

I found the 90-9-1 rule about volunteers to be true. 90% of the people on any community project remain quiet lurkers; 9% contribute moderately, and 1% contribute actively. But even with just 9% + 1% of people contributing, the volunteer writing effort showed some fruits. We generated about 18 articles in total (over a period of about 6 months). It seemed superficially successful.

Then I started measuring times. I began to realize that the overhead of getting volunteers to write outweighed the time I spent managing the volunteers. If it took 2-3 hours to manage a volunteer through the writing cycle, or an equivalent 2-3 hours for me to write the article myself, was I really gaining a lot?

One barrier insiders frequently ran up against was the inability to access knowledge behind the firewall. Volunteers didn’t have access to the insider resources they needed. They didn’t have any of the following:

- JIRA sites

- SharePoint sites

- Test environments

- Internal contacts

- Product roadmaps

- Team standups and other meetings

In short, they lacked the information, resources, and contacts to actually get the information they needed to write the articles. But if I had to get all this info and somehow transfer it to the volunteer writer, I felt I’d done most of the work already.

Besides contributing to the blog, some people also made edits to docs on the wiki. But the same problems existed. All contributions happened post-release, so their edits were applied to existing docs. The people who made edits to existing docs usually did so in awkward ways that required fixing or other edits.

To make an addition to docs, you can’t just add a paragraph wherever you want. You have to understand the whole so you know what exists and where. You also have to understand doc style and conventions and voice so that your content can fit seamlessly in. It’s not so easy, especially for someone who might not want to dedicate much time to this effort.

Ultimately, I don’t remember more than 10 small edits to tech docs overall.

Eventually, the efforts to crowdsource the blog and wiki died. I explained why the effort failed:

I tried the volunteer writing model for more than a year. I kept thinking that if I just figured out the right approach, it could take off into endless productivity. With 100+ writers creating content on a regular basis, we could publish new blog posts daily. We could translate documentation overnight. We could sketch out a skeleton of tasks to write about, and then have volunteers fill in the details. It didn’t happen.

The reasons, as I have stated, can be summarized in three bullet points:

- Writing requires insider knowledge that volunteers lack.

- Professional writing standards are usually beyond volunteer capabilities.

- The management overhead in coordinating volunteer writing barely outperforms the return.

This marked a turning point for me in using wikis as a collaborative platform.

Because collaborative writing failed, I didn’t see any need to continue using wikis as a platform, since help authoring tools could provide more robust outputs in different formats.

To make crowdsourcing work, you have to chunk tasks into a little, almost effortless pieces of work. When you multiply that tiny effort by thousands of contributors, you suddenly have something significant.

I compared the crowdsourcing strategy to moving projects. If you put everything in boxes, each volunteer can easily grab and carry a box. But if everything isn’t already packed up in easy-to-transport boxes, the volunteers flounder.

But writing doesn’t granularize into little effortless chunks/boxes like that, so these efforts fail. For example, you can’t ask 100 people to each write 1 sentence in an article.

I also found that you don’t need a wiki to enable collaboration. In fact, volunteers preferred to make edits to Word documents shared via Dropbox. I wrote:

Many volunteers who write articles are uncomfortable publishing them directly on the wiki. They prefer to write in Microsoft Word and upload the articles to Dropbox or JIRA…..When I started to realize that wikis weren’t a necessary platform for interacting with volunteers, I started to rethink the wiki as a platform. You can have a lot of success with community and collaboration without using a wiki at all. In fact, because the content is not being published live, for the whole world to see and immediately interact with, volunteers actually feel more comfortable contributing.

This is a significant observation that is worth expanding on. In my experience, most engineers don’t want their content to make it directly into production, without an editorial workflow. This is their worst fear, actually. They want to do quick brain dumps on internal wiki pages (or in Word docs) and send them to tech writers to clean up, verify, and polish before publishing.

Now back to Docs as Code

With that context, let’s look at docs as code again. Suppose you’re implementing docs as code for purposes of crowdsourcing docs among engineers. If writing docs isn’t the engineers’ main job, the result will likely be the same as crowdsourcing efforts with wikis – dismal.

Sure, there will be some shimmering lights here and there. Just like some wikis were (or are) successful. But in general, the majority of tech writers who try to crowdsource their docs will find a lack of significant contributions. The contributions they do get will demand editorial and management overhead.

(Note that from a tech comm career perspective, this is good. This means companies can’t crowdsource you out of a job. No new tech platform or workflow is going to make that magic river of free documentation start flowing.)

Where wikis took off and skyrocketed

Wikis may have died out with docs as a way to crowdsource info, but they didn’t die out as a corporate platform. Wikis, in fact, have become the standard corporate platform for employees to share and publish information. Wikis such as Confluence have largely replaced SharePoint.

In my last 3 jobs, wikis were used across the company for employees to write and publish internal information. In my current job at Amazon, there are at least a million internal wiki pages (across multiple wiki platforms – Mediawiki, Confluence, and XWiki). Why? Because wikis give people easy tools to do their jobs. (Or at least it simplifies the part of their job that involves sharing information.)

Docs-as-code tooling can have similar gains. It can empower engineers to do their jobs as far as documentation is concerned. If it’s the engineer’s job or role to document something, the engineer will be more likely to do it using the coding tools and workflows familiar to them.

Even for non-engineers, giving people a simple tool and publishing workflow can help people author and distribute content. The simple tool might be Markdown syntax and a repository that automatically builds and deploys the content.

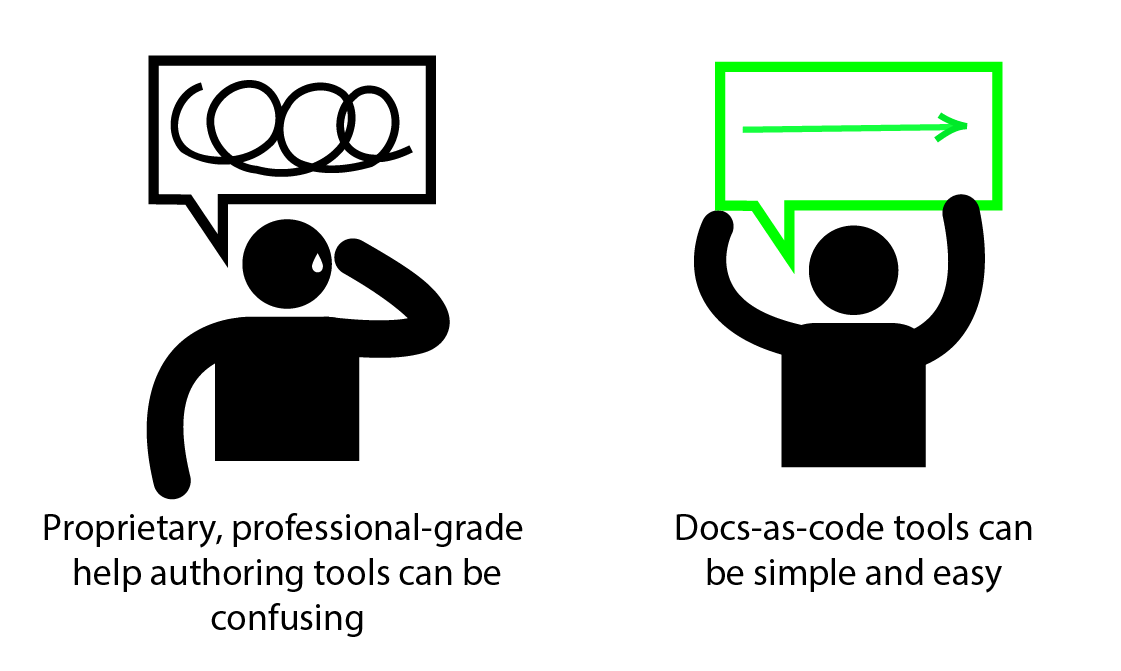

Again, forget about crowdsourcing. Docs as code is giving people simple, free, open-source tools to do the writing/publishing tasks they need to do. For that purpose alone, docs as code has the power to move beyond just being a fad. There is real value in empowering common people to author and publish content (without expensive help authoring tools, without knowledge of XML syntax, without years of professional tech writing know-how, etc.).

Simplification of authoring and publishing tools is at the heart of the docs-as-code movement. No more black boxes that handle your content. No more expensive, proprietary systems to submit to. No more impossible-to-adjust-outputs-unless-you-know XSLT/XSFO-XS-whatever to style your output. You can integrate it all simply, easily, and inexpensively. It works with other web tools and other systems too. You can integrate with the latest web technologies and tools. You can leverage help from modern UX devs.

Here are some of the revolutionary benefits that docs-as-code tools provide:

- Read in plain text with Markdown (or other similar lightweight syntax). You don’t need a special editor to provide a WYSIWYG display because of all the angle bracket tags.

- Manage files as plain text (rather than binary files only machines can read). This allows version control systems like Git to do diffs on the content.

- Manage files in version control repos. You can branch content to manage multiple versions without creating various copies of files. You can collaborate in a distributed fashion with multiple team members.

- Automate builds and deployment of your content from repos using scripts. Because you’re working with simple text files, you can integrate this content into deployment scripts.

In my GitHub repo, there are active contributions from a writer who is our localization manager. She’s been editing the Japanese translations. When we started, she was only marginally familiar with basic HTML. But with docs-as-code tools, she regularly updates Markdown files, commits to the repo, pulls updates, and runs build scripts.

Simplicity has its tradeoffs

Simplicity has its own tradeoffs, though. In exchange for simpler tools, you give up more robust functionality. In a recent comment on a previous post, a reader who was accustomed to using DITA and DocBook for over a decade lamented about the loss of switching to Markdown. Kate writes:

I am desperately trying to embrace Markdown after 10 years of using DocBook and then DITA. But I am increasingly finding it difficult.

I’m not certain that building/generating docs from Markdown is that much simpler. I think that a lot of customization is still required to get a nice output. And if people are increasingly adding HTML in order to be able use a table or to create an ID for a section, are we really making things that much simpler? There seems to be a lot of customizations and plugins, etc to do things like check links–these are great, but they can easily become out of date.

I miss having the concept of a map file that contains pointers to my topics.

I miss using oXygen. I miss it’s SEARCH. I miss using it’s link checker. I miss seeing reused content appear inline in my topic. I miss being able to filter out conditioned content. I miss wysiwig table editors and I miss seeing my images inline. I miss seeing tag errors inline. I am a fairly technical person–I often used the text editor more than the Wysiwyg editors…

While some aspects of authoring are simplified, others – such as developing your own custom output, or engineering search functionality – become more complex. In the end, you have to weigh whether the simplification of some aspects is worth the complication of others.

For example, is writing in a simple Markdown syntax worth it if it makes it more problematic to push your content through translation workflows? Is a system that allows for occasional edits from contributing engineers worth it if you have to develop a number of custom, complicated programming scripts to validate, build, and deploy your content?

Conclusion

If you can cultivate a community where devs contribute their time and attention to docs, great. But if the crowdsourcing efforts fail, it doesn’t mean docs as code or even wikis failed. You’ve still given people simple tools to write and publish documentation.

Although I mentioned crickets as a response for crowdsourcing docs in my current role, it’s not entirely fair. We do have several groups outside of our own that learned the doc-as-code tools and published their docs. They didn’t edit my docs – they created their own.

Regardless of the participation, I’m planning to leave my docs on GitHub for a lot longer before evaluating the efforts. I suspect it’s too early to evaluate much of anything. Most engineers probably don’t realize they can edit docs, so I have some education efforts to make both internally and externally. Only after I get the collaboration engine moving along can I begin to evaluate whether the tradeoffs for simplicity were worth it.