Limits to the idea of treating docs as code

First, what we mean by docs like code

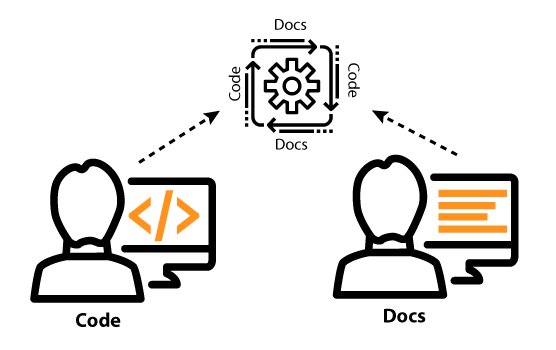

Before I draw limits around docs like code, let me briefly describe what “docs as code” means. To treat docs like code generally means doing some of the following:

- Working in plain text files (rather than binary file formats like FrameMaker or Word)

- Collaborating using version control such as git and GitHub (rather than collaborating through large content management systems or SharePoint-like check-in/check-out sites)

- Automating the site build process (rather than manually publish and transfer files from one place to another)

- Running validation checks using custom scripts to check for broken links, improper terms/styles, formatting errors, etc. (rather than spot checking it manually)

- Storing docs in the same repositories as the programming code itself (rather than keeping it separate in another space)

- Versioning docs through git tags/releases (rather than duplicating all the files to archive each release)

- Using an open-source static site generator like Sphinx, Jekyll, or Hugo to build the files locally, using your customized theme with all files open and editable in an IDE-like editor such as Atom (rather than relying commercial tools with proprietary, closed systems that function like black-boxes)

In short, treating docs like code means to use the same systems, processes, and workflows with docs as you do with programming code.

Few people do all of the above points. For example, it doesn’t make sense for me to store my docs in the same repos as code, because most of the code repos are never deployed publically, and even if they were, engineers release much less frequently than tech docs. This brings me to my main point: docs aren’t just like code, and we should probably not push this docs-as-code treatment too far.

When docs aren’t like code

Here are a few ways that docs aren’t like code:

Release frequency

Engineers like to release updates a lot less frequently than tech writers. For example, one open source project I work on has quarterly releases. They do this for good reason. They don’t want to keep updating the code so frequently that they exhaust the patience of the third-party developers. A lot of changes to code aren’t always backwards compatible, and if engineers published an update to code every two weeks, the Trump-like pace may be seen as out of control and haphazard.

In contrast to code, docs should be released much more frequently. If you see a typo, fix it and push out a new version of the documentation. As pull requests come in identifying broken links, or you need to add a little note here and there based on current usage, you should do so freely and regularly — much more regularly than with code releases.

If your doc is trapped in the same repository as the code, you won’t be able to push out releases very quickly. Separating docs from code release cycles allows you to be much more agile and iterative with your docs.

Most likely you won’t have power to commit to the same code repo at all. Engineers are usually more meticulous and systematic in their commit messages and release methodology. They need to be, since they’re changing the functionality of how something works. They may even reference JIRAs in commit messages. In contrast, when you’re fixing commas in a sentence, an elaborate commit message is overkill. I usually type a quick, hasty commit message and push it to my docs repo.

I know I could do better with my commit messages, but I honestly don’t think users read them. If they want to see what’s new, they check out the release notes. Developer users often look at commit logs because, outside of code comments, it’s often the only place where developers write anything.

Despite the challenges in integrating with code repositories, I still keep my docs in a git repository, which I push both to an internal git repo and to an external GitHub repo. Git is an ingenious solution for collaborating with others as well as organizing your docs (through branches) as you work on various features.

Release complexity

Let’s look at another aspect of docs like code. When you release code, you usually push it through a QA process where QA teams tests the code rigorously against a long list of detailed test scripts that analyze major scenarios.

After QA completes their testing (both automated and manual, as well as with different strategies — regression tests, smoke tests, and more), they certify a release build that moves through a series of deployment stages, from alpha to staging environments and finally to production environments. You most likely have a publishing pipeline that moves content from one environment to another through the command line with different scripts.

When you publish code on a server, that server usually needs to pass a number of checks to ensure that it has sufficient firewalls and security. You also probably need a redundancy plan (virtual redundant clusters) in case the server goes down.

With docs, you’re lucky if you get one engineer to read the content (let alone anyone to test it, especially from QA) before it’s published. Docs simply aren’t in the scope of QA (though they could be). You also don’t have automated scripts to run through with your documentation steps. At most you may have an editor to check for style (editors are now an endangered species), a tool like Acrolinx to look for terms (if you work for a large company with deep pockets), and maybe a link checker to look for valid links.

But you don’t need a super heavy process process for deploying docs. If you’re building your output locally, you just need to transfer HTML files to a web server. You could literally download any FTP client and transfer files this way (if companies would allow it).

If you let engineers define your deployment process for docs as code, you might end up with something heavy, complex, and total overkill (because they’re following the same deployment strategies as code) for what is essentially a two-minute file transfer task. In short, if you really treat docs like code, you can end up over-engineering the deployment solution.

Review processes

If you’ve ever tried to review docs using tools like GitHub, which has the best interface by far for code reviews, it’s cumbersome. I’ve participated in a number of doc reviews with GitHub for Jekyll’s docs, and I find GitHub awkward and inefficient. Tools like Google Docs or even Microsoft Word work much better at facilitating conversations around specific points in your docs.

If you try to use more code-intensive review tools like Review Board, the views will show only what has changed in the latest commits. But with documentation, reviewers usually need to see the whole document in its published form to view it effectively. You can’t just look at lines that changed here and there.

Further, code review tools show the code view, which is harder to process than the browser-rendered view. GitHub lets you comment inline in the code, but looking at the code, you won’t know what it looks like when rendered by the browser. That browser rendering is important to see images, styling, and other formatting. I’m not saying an engineer couldn’t toggle between the rendered output and the code view, then make comments in the code view. But it’s awkward because you have to keep shifting between two views and re-finding your place on the page.

Further, most engineers (ironically) won’t review your docs using code review tools. Most engineers I’ve worked with prefer to provide comments in email threads, Google docs (if allowed), or Word files.

Company support

Another way that docs differ from code is in the degree of company support. This point isn’t straightforward, but be patient because it’ll get clearer as I go.

Engineers work on code as their primary deliverable, while tech writers work on content. As such, engineers have financial backing and resources to buy and operate servers and other technical frameworks, and they can devote most of their time to the code-related tasks. In short, engineers work on code projects that have the full backing of the company, because those code products are what the company will be releasing, selling, and supporting.

If you implement a docs as code approach, you’ll probably find yourself knee-deep in similar technical frameworks, but without the same company support to dedicate time and resources to support those technical frameworks. Companies want writers to focus on content, not on tools. The more bandwidth your tools require of you (and a docs-as-code approach seems to require a lot of custom coding tasks), the less time you have to work on company-sanctioned and encouraged content efforts.

At practically company I’ve ever worked at, the doc team has been responsible for their own tooling and doc platform. If engineering resources are used, they’re only briefly borrowed. The tech writers usually bang out the whole doc solution from beginning to end, in between releases where they’re expected to produce content, not tooling around the content.

Tech writers are paid to write content. You do the tooling either on your own time or you squeeze it between the demands of content creation. As such, it’s a impractical to expect tech writers to follow a robust docs-like-code model, deploying code through various server environments using complex scripts and other engineering-heavy resources.

Additionally, most companies restrict interactions with servers to engineers or operations teams as well. Tech writers will usually not have access to deploy their own code to a production server without going through the same engineering heavy security and audit checks as programmers.

This is why for years, tech writers have purchased third-party authoring tools and delivered a zip file to engineers to push the content to a server. Tech writers simply don’t have company support or backing, not to mention the technical depth, to sink time into code development like engineers do. If you want to treat docs like code, but you don’t have time or company support to develop the tooling to support docs like code, you’ll face an uphill battle to make it work.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although I like the docs-as-code idea and enjoy working with some of these approaches, docs aren’t entirely like code. Docs differ from code in release frequency, release complexity, review processes, and company support.

You may have implemented your docs-as-code approach with much more success in some of these areas — if so, great. Let me know how you worked around the issues I noted. But don’t mistake apples for oranges. Documentation isn’t programming code. We’re writing in conversational sentences, not functions and loops that can be validated and automated. There are significant differences that we shouldn’t over look when working with docs.

Documentation is different from code in ways that deserve not only to be noted, but celebrated. For example, here are a few unique qualities with docs:

- Docs are written in simple, conversational language that you can say out loud.

- Docs can be iteratively updated each time someone reads it and provides feedback.

- Docs help you perform a task in a company product; they usually aren’t the product themselves.

- The quality of docs is subjective, and the comprehension/readability varies based on the user.

- Docs can connect emotionally with an audience.

Sure, you could probably say similar things about the readability of code among programmers. But documentation surely differs from programming code in significant ways that deserves some acknowledgement. Given that docs are different from code, should we really be treating them the same way? To some extent, sure. But let’s not get swept away drinking too much of the docs-as-code koolaid.