Results from my Academic/Practitioner Attitudes surveys now available

Survey results

Here are the results for both practitioner and academic surveys:

-

Practitioner responses: Infographic report | Dashboard report

-

Academic responses: Infographic report | Dashboard report

QuestionPro (the survey tool I used) provides various ways to present the data. I presented two versions here. I think the Infographic report is a bit more scannable and easy to read, but the Dashboard report provides more details.

Background on the survey

I initially started shaping the survey topics by asking open-ended questions that invited people to respond. I received about 30 responses with a lot of feedback to read through. Working with a professor interested in the project, we then formulated the responses into a representative list of agree/disagree statements (a Likert scale) whose responses could be quantitatively measured.

I kept the survey open for 2 weeks and, in total, collected 407 practitioner responses and 65 academic responses. As this second survey was a quantitative measure, it gave me a specific number as a baseline to compare later responses.

My plan is to now start the “conversations” phase of my project. I describe this in more detail here: Academic/Practitioner Conversations. The basic idea is to create conversations (in the form of Q&A posts, guest posts, podcasts, and other exchanges) between practitioners and academics by pulling them both into the same (virtual) space as a means to lessen the divide.

Interpreting the survey results

Now that the survey results are in, what do we make of the responses? I invite your interpretation and feedback, as data is not always easy to interpret. I feel the most significant response is the answer to the first question:

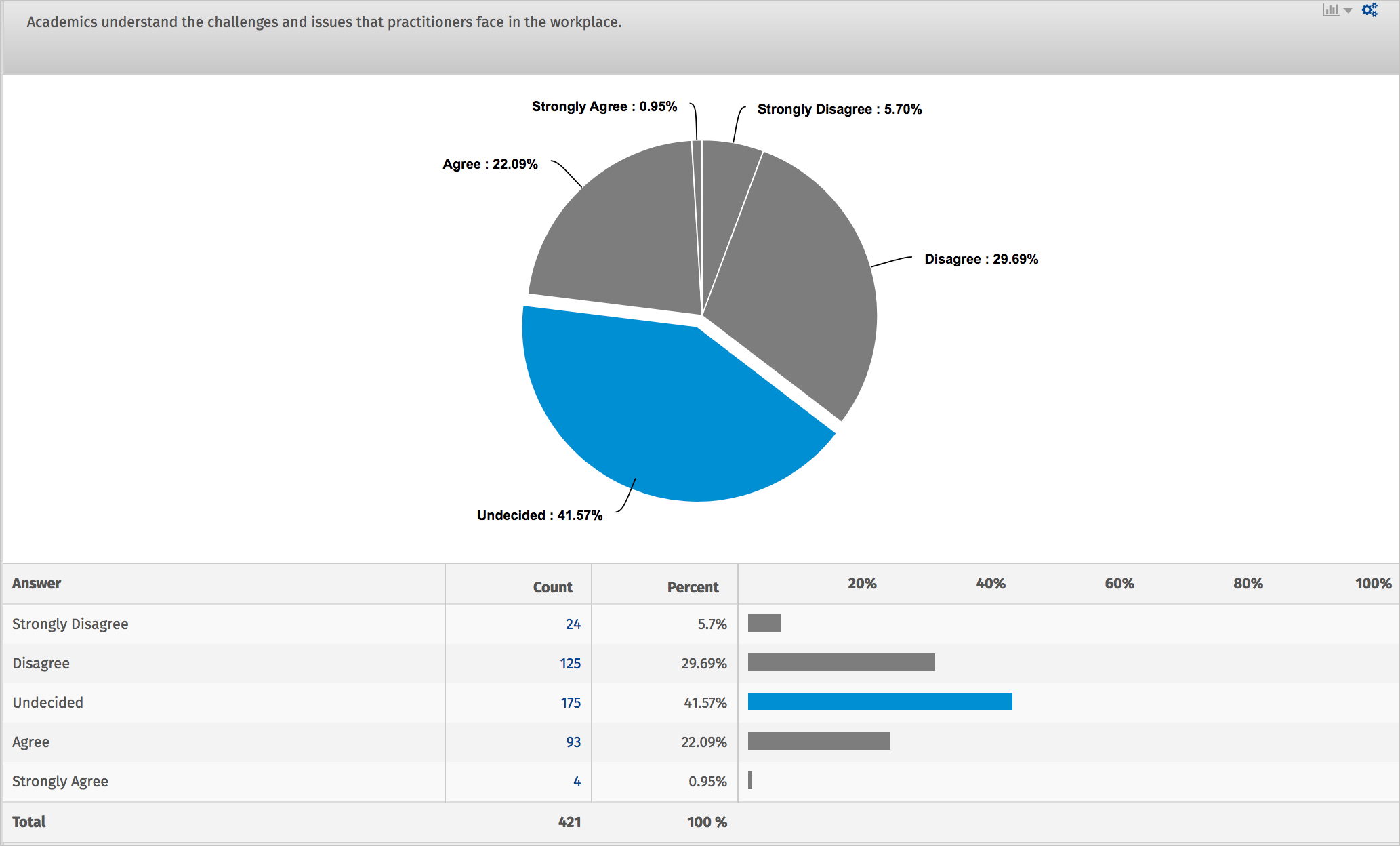

Academics understand the challenges and issues that practitioners face in the workplace.

Here’s a breakdown of the responses:

The responses here are varied. If you just look at the overall distribution, the 2.83 score appears as if most are undecided (42% are undecided). But the responses are also a bit polarized. About 35% disagree or strongly disagree, and about 23% agree or strongly agree.

I’m not exactly sure how to interpret this result. It seems like many of the survey statements that follow hinge upon the answer to this question. If you’re undecided about whether academics understand the challenges in the practitioner’s workspace, how can you agree that “practitioners should read academic research publications” or that “research from academics helps advance the field” or that “the research conducted by academics is relevant”? If you’re undecided as to whether academics understand practitioner issues, you can’t really agree with the other statements except as a gesture of soft (but empty) optimism.

Overall, it’s troubling that so many practitioners are undecided. It would be better if they either agreed or disagreed — at least then practitioners would be making a more informed decision. But today we have entire communities of practice sprouting up (e.g., Write the Docs) that have very little knowledge of (or exposure to) any of the research produced by TC academics.

For those who did take a position (other than undecided), the fact that 36% either disagree or strongly disagree should send a wake-up call to the academic community that something is wrong.

Now let’s flip to the other side and look at the results from the academic survey. What stands out most to me is the response to this statement:

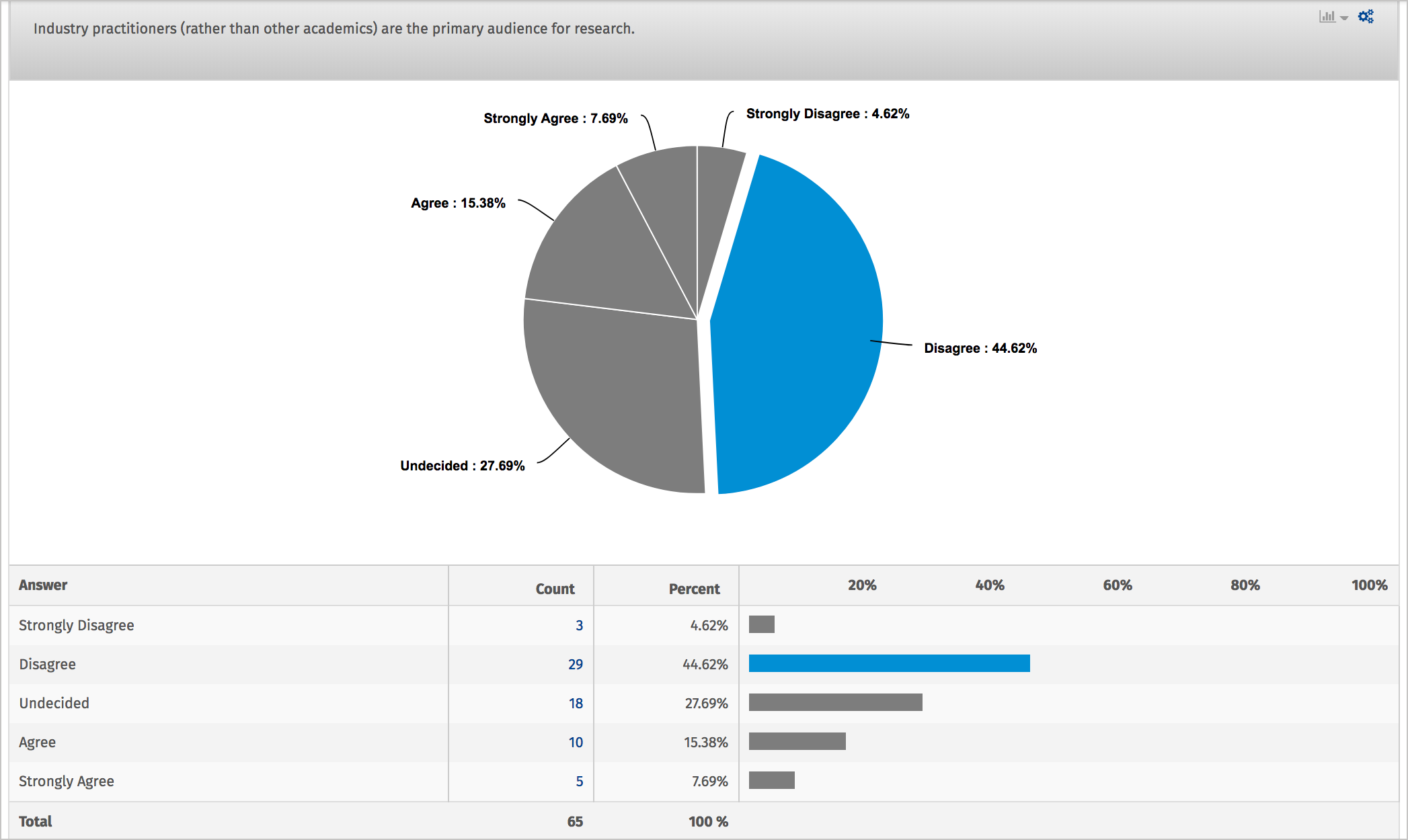

Industry practitioners (rather than other academics) are the primary audience for research.

Here’s a breakdown of the responses:

About 50% of the academic participants either disagree or strongly disagree that practitioners are the audience for their research. 28% are undecided, and only 23% agree or strongly agree. Holy smokes! Notice that the question didn’t say that practitioners should be the audience for academic research, so maybe academics believe that the current state isn’t the ideal or desired state. But is it any surprise that practitioners aren’t diving into academic research given that they aren’t the audience for it? (And if they aren’t the audience, then practitioners’ disagreement with the relevance of academic research makes sense.)

Let’s think more about this question and our assumptions. Should academic research be geared towards practitioners? Technical Communication journal articles do have a section called “Practitioner Takeaways,” which suggests that practitioners are a target audience. But taking the survey responses here at their word, even Practitioner Takeaways aren’t really intended for practitioners.

If academics aren’t doing research for practitioners, who is their research for? It could be that academics like to explore issues of communication and technology purely for its own sake, without any connection to the industry or workplace. For example, how does technology impact the way humans communicate with one another in society? Academics might explore these questions independent of any actual application to the issues technical writers face in the workplace, let alone something so mundane as software documentation. Such an independent, academic-centric focus would be justified in philosophy, or literature. But tech comm?

Here’s another way to interpret the survey response. Even without practitioners reading journals, academic research will trickle down into practitioner workspaces on its own. It’s like the news — even if you don’t read or watch the news, you still get a sense of what’s going on. You hear about it from somewhere (someone circulates it), even if you don’t know the source. Consider how many end-users don’t actually read the documentation, but they learn about the right techniques through support agents who do read the documentation. Thus, in this model, academics might be writing for other academics without worry about excluding practitioner audience. They are writing for practitioners indirectly.

A similar argument is that, in academic journals, academics write for other academics. These are, after all, academic spaces and clearly, based on the methodological details and academic discourse, academics don’t have practitioners in mind. But, as Bob Watson explains in the comments below, “Academic researchers share and build on [each others’] research and, after a while, some will take this body of knowledge and write a book (blog post, conference presentation, etc.) for practitioners.” In this view, academic journals are a place for academics to rightly exchange with other academics, and eventually, the information that holds up finds its way to practitioners through other forms.

But notice that the survey statement didn’t mention journal articles at all. It stated, “Industry practitioners (rather than other academics) are the primary audience for research.” Perhaps the split responses to the question are due to how respondents interpreted the word “research.” Does it refer to the research projects academics undertake as a whole, or to the published journal articles about their research? One would hope that the projects do have practitioners in mind as an audience, even if the (initial) publications ignore that audience.

A final, more cynical interpretation of this response is that the research academics do stems from the pressures for tenure, and so the academic’s real audience is the tenure committee. They cannot appease the tenure committee (which demands academic discourse, scientific methodology, thorough literature reviews, and a grounding in “rhetoric”) and also appease practitioners (who look for simple and direct information related to their jobs, often preferring more technical and practical guidelines). Thus, just as we all adhere to the power of the paycheck, academics write for their true audience — other professors who will give them a thumbs up or down on tenure. In this sense, academics simply inhabit another kind of corporate workplace.

Conclusion and next steps

The divide between academics and practitioners is a sorry state of affairs (though it’s not unique to our discipline). What can we do about it? I’m going to start a project that I’m calling Academic/Practitioner Conversations. Part of the problem, as academics such as Stacey Pigg have pointed out (in her article on Multidirectional Knowledge Flows), is that academics and practitioners have different knowledge flows; they operate and interact in different spheres and spaces. One goes to conferences and reads blogs, the other goes to the library and talks with students in the classroom.

The idea behind my research project is to bring these two groups into a common space where they can interact through conversations. Over the course of the year, I’m planning to have conversations (in the form of question-and-answer posts) with academics about their articles and research. I invite others to join me as well. These conversations will take the form of blog posts and podcasts. More than any other site, I want I’d Rather Be Writing to function as a bridge between academics and practitioners.

After a year of conversations — conversations that will hopefully forge partnerships on projects and research — I will send out this same survey and see if we’ve moved the needle on any responses.

More than just influencing attitudes that each group has about the other, ultimately I hope to diminish the width of the divide a bit. I want academics to start undertaking research that is more relevant to practitioners, and I want practitioners to start leveraging academic research to inform workplace decisions. As we influence each other, both groups will move forward in more informed ways.

If you’d like participate in this effort, I created an email group called Academic/Practitioner Bridge dedicated to this purpose. If you’re an academic who wants to collaborate with practitioners, or if you’re a practitioner who wants to collaborate with academics, be sure to sign up. The email group will facilitate questions from one camp to the other. For example, practitioners looking for research about “X” can send an email with the request, and academics can respond. Likewise, academics looking for information about “X” for their research can send an email with the request, and practitioners can respond. (At least that’s the idea.)