Tech comm trends: Providing value as a generalist in a sea of specialists (Part II)

<div class="btn-group">

<button type="button" data-toggle="dropdown" class="btn btn-warning dropdown-toggle">Tech comm trends: Providing value as a generalist in a sea of specialists<span class="caret"></span></button>

<ol class="dropdown-menu">

<li>

<a href="/2018/10/02/providing-value-as-generalists-in-specialist-contexts-part-1/">Part I: Introduction and argument overview</a>

</li>

<li class="active"> → Part II: Why tech writer jobs are moving toward the developer domain</li>

<li>

<a href="/2018/10/02/providing-value-as-generalists-in-specialist-contexts-part-3/">Part III: Gaps in documentation tooling and processes</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="/2018/10/02/providing-value-as-generalists-in-specialist-contexts-part-4/">Part IV: User knowledge and understanding</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="/2018/10/02/providing-value-as-generalists-in-specialist-contexts-part-5/">Part V: Information usability principles</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="/2018/10/02/providing-value-as-generalists-in-specialist-contexts-part-6/">Part VI: Information usability principles continued</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="/2018/10/02/providing-value-as-generalists-in-specialist-contexts-part-7/">Part VII: Conclusion</a>

</li>

</ol>

</div>

The impact of UX and the need for documentation

It seems that technology is getting simpler on the front-end for mainstream end users, but also more complex on the backend with development. In a recent episode of the Cherryleaf podcast, 40. The evolution of the technical communicator’s career, Ellis Pratt discusses an article called Software technical writing is a dying career (but here’s what writers can do to stay in the software game), by Jim Grey published in 2015.

Grey’s main argument is that “companies are leaning into good user-interface design and stepping away from online Help systems and printed/PDF documentation.” Grey explains that he had lunch with a business owner who explained this transition, saying:

Technical writing is dying off…. It’s all about clean, engaging UX now. I have talked to more than a hundred startup and small software companies as I’ve built my business. Almost none of them have technical writers, and almost all of them have UX designers.

Grey argues that UX design has displaced the need for tech comm in software companies. Instead of hiring a tech writer to provide explanations for confusing interfaces, companies (at least those that want to be successful) hire UX designers to get the design intuitive from the start.

Companies recognize that a usable interface can easily work with can make the difference between success and failure. Companies like Apple have cemented the idea that users are willing to pay for well-designed products that don’t rely on a lot of documentation.

Obviously, products that don’t need docs because they’re so intuitive will likely be more successful among end-users than products that require docs to figure out. So if you want your company or product to be successful, it’s clear where you need to spend your money: UX, not tech comm.

Riding this demand, the practice of user experience design has matured into a full-fledged discipline rich with research-backed design principles, methodology, and professional expertise. UX designers are now much more common in engineering groups.

The consequence of this increased emphasis on UX design is that there is less need for user guides to accompany end-user products, especially those with user interfaces. You might have UX copywriting needs, but you don’t usually need an extensive user guide for a product because if users need documentation, your product itself will likely fail. Better to invest in good design from the start.

Sensing his irrelevance as a technical writer, Grey jumped off the documentation ship and into software testing instead, where he says he brought along many useful skills he learned in documentation.

Evaluating Grey’s argument and changes in the profession

How do you evaluate Grey’s move? Was he right or wrong about his conclusions that tech comm is dying? It’s probably not possible to make any conclusion about tech comm jobs declining (as a result of UX design) without a comprehensive analysis of tech comm job postings analyzed over the past two decades.

In the Cherryleaf podcast, Pratt looks generally at job trends and concludes that no, technical writing jobs haven’t gone away. Pratt says:

Is this true? Has the tech writing job disappeared since 2015? Clearly not, because there are still … [many] technical writers and authors. But I think there is a truth in saying that the role of the technical author is changing, and the requirements and the skills that they need are changing as well. And it may be that the job title changes and the way in which the role is perceived.

In other words, he says the jobs haven’t disappeared, but the roles have evolved. This evolution of the tech comm role is what I’m exploring here with my focus on trends. I agree with Ellis about the evolution. The job landscape for technical writing has changed, not necessarily gone away.

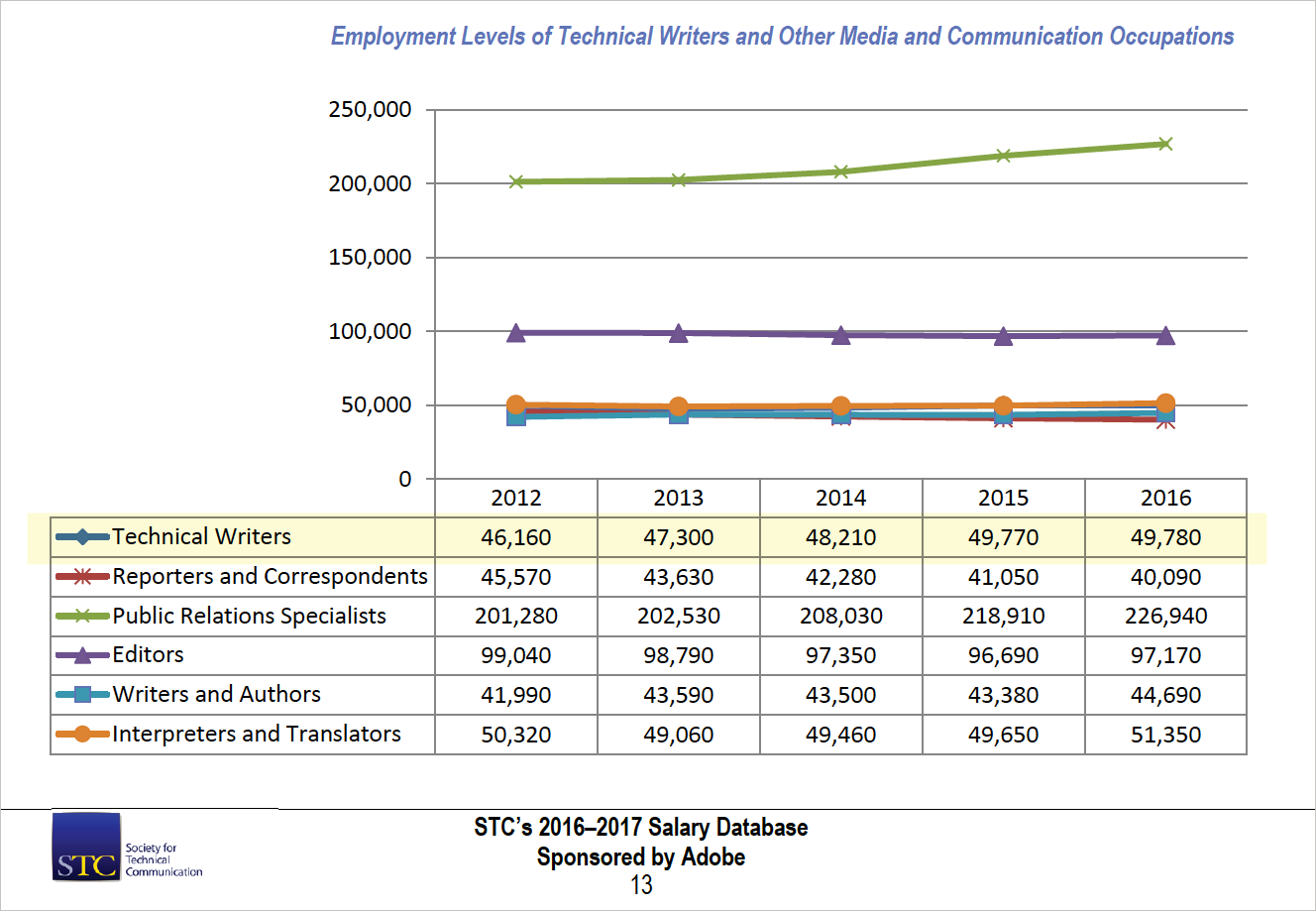

If you look at the latest STC Salary Database, you can see that tech writing jobs have largely remained the same since 2012:

Plus or minus a few thousand jobs, there are about 50,000 technical writing jobs in the United States. This information comes from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, or BLS. Among professional writing disciplines, the report notes that technical writing is “the only occupation which has seen employment growth in each year since 2011, with an average annual employment increase of 1.9%.”

So tech writer jobs haven’t simply disappeared because of the emergence of what is sometimes called the “Golden Age of UX design.” But while tech comm jobs haven’t diminished, they have likely shifted more from the end-user domain to the developer domain.

UIs getting simpler, behind-the-scenes code getting more complex

While user interfaces are often getting simpler, the code behind them is getting more complex. The classic example of this shift towards simple frontends and complex backends is Google’s homepage. On the surface, it looks pretty simple. But go to View > Source and copy the code on that page, and then paste it into Microsoft Word. It’s 73 pages long!

Consider another example: voice interaction. When I say to my Fire TV, “Alexa, show me the latest action movies,” this natural language interface attempts to simplify the user experience. There’s no need to find the right menu, to type out my search using the remote controller’s direction pad, and so on. But behind the scenes, making this simple natural language interaction has an incredible amount of complexity and code. There are multiple systems interacting in harmony with each other — or sometimes clashing, which can result in Alexa misinterpreting your utterance and returning something unexpected.

Technology is like an iceberg — seemingly simple on the surface, but with massive amounts of code underneath.

Technical writers are always needed where there’s complexity — if there’s nothing complicated or sophisticated, tech writers are extraneous. Hence, this complexity is pulling tech comm professionals more toward developer documentation, away from end-user documentation.

This trend toward increased complexity underneath the surface is particularly apparent in UX development itself. In a comical article called How it feels to learn JavaScript in 2016, Jose Aguinaga contrasts what it’s like to learn JavaScript today versus a number of years ago, presenting it in an imagined conversation with a newbie developer. Here’s a quick excerpt:

I need to create a page that displays the latest activity from the users, so I just need to get the data from the REST endpoint and display it in some sort of filterable table, and update it if anything changes in the server. I was thinking maybe using jQuery to fetch and display the data?

-Oh my god no, no one uses jQuery anymore. You should try learning React, it’s 2016.

Oh, OK. What’s React?

-It’s a super cool library made by some guys at Facebook, it really brings control and performance to your application, by allowing you to handle any view changes very easily.

That sounds neat. Can I use React to display data from the server?

-Yeah, but first you need to add React and React DOM as a library in your webpage….

Aguinaga goes on to explain how jQuery, Bootstrap, and Bower are now passé. He then walks through about 30 confusing JavaScript frameworks and technologies that front-end developers need to sort through when coding, explaining the need for React, JSX, Babel, ES6, Browserify, WebPack, VueJS, RxJS, Grunt, Gulp, Broccoli, SystemJS, Typescript, OCaml, Ramda, Fetch, Request, Bluebird, Axios, Flux, Flummox, Alt, Fluxible, Redux, SystemJS, and dozens more JS frameworks and tools.

Moving into hyperspecialization

Aguinaga’s article illustrates how, for the past few decades, technology (at least behind the scenes in the realm of development) has been getting more and more complex and specialized — more extensive, varied, complicated, and deep. The engineer who implements the frontend of a site has a very different skill set from the one working on the backend.

For fun, think back to a time when we had “webmasters.” The idea of a “webmaster” — a person who handles all aspects of a website — is an especially dated idea. This specialization has permeated all aspects of technology organizations. Today, you’re not just a “software developer.” You’re a JavaScript developer for web apps, you’re an Oracle database specialist, you’re a release management configuration engineer, and so on.

We have these specialists because complexity has increased. The idea of a Renaissance tech person, one who can adeptly navigate across UX design, frontend and backend technologies, publishing systems, middleware infrastructure, server configurations and deployments, or even web metrics, is rare. We all specialize in something.

An article in the Harvard Business Review noted that we’ve even moved past specialization into “Hyperspecialization.” The authors explain,

Just as people in the early days of industrialization saw single jobs (such as a pin maker’s) transformed into many jobs (Adam Smith observed 18 separate steps in a pin factory), we will now see knowledge-worker jobs—salesperson, secretary, engineer—atomize into complex networks of people all over the world performing highly specialized tasks. (The Big Idea: The Age of Hyperspecialization)

The author even notes that with some encyclopedia articles, different paragraphs within the same article are sometimes written by different specialists. Each specialist-written paragraph fits together into a larger article.

For more on how the level of complexity is increasing, check out a book called Overcomplicated: Technology at the Limits of Comprehension, by Samuel Arbseon. The author talks about how we’ve built systems that very few people fully understand, and these systems are interacting with other systems in ways no one can fully predict. Sometimes when these complex systems have bugs (such as with Toyota’s acceleration problem), we end up scrambling through millions of lines of code across many different systems, looking for the problem.

The developer domain lacks UX designers to vet and filter poor designs

So the developer domain is complex. We know that. But here’s one more detail that makes it even worse: In the developer domain, UX designers don’t vet and filter out poor designs.

When companies develop an API or SDK, usability professionals (champions of simple interfaces) aren’t usually involved in the API or SDK’s design. Developers usually build their own tools, without taking guidance from UX designers.

Theoretically, UX designers could prototype mocks (such as using the OpenAPI with REST API designs) and beta test them with the target developers, but this spec-first philosophy is somewhat rare, and if done, isn’t usually led by usability professionals. Engineers usually feel that they know what’s best for other engineers.

As a result, developers are left on their own when it comes to designing their APIs, SDKs, and other technical frameworks. (After all, they’re often the only ones who understand them thanks to specialization.) What’s the result?

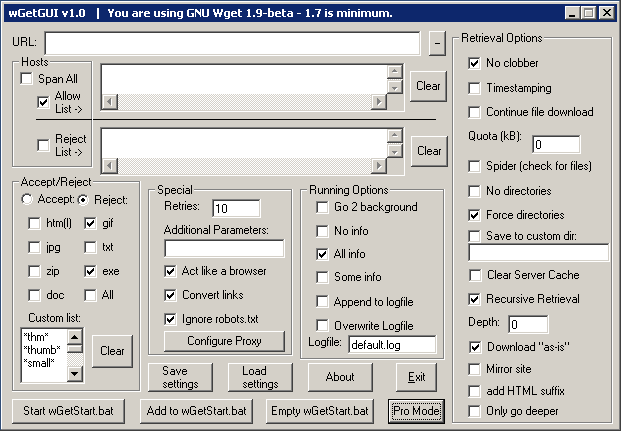

The outcome, when engineers play roles in design (even code design), is often parallel to the outcomes when developers created user interfaces. Remember back before UX designers were common, engineers would create user interfaces that looked something like this:

Looking at this, we laugh. But when developers create developer products (that is, tools for developers), the result is often the same but less visible because developer products don’t often have interfaces. Developers create code spaghetti and kluges, with really confusing processes and setups.

Recently in a Write the Docs Slack channel, during a discussion about how to handle documentation for broken products, someone said,

I remember a colleague at a previous job getting told off for prefacing some instructions with something along the lines of: “You need to follow every step of these instructions to the letter, even if they seem weird or pointless, otherwise the whole thing will break.” … It was a fantastic way (IMO) of demonstrating just how broken the product was. (Transparency in documentation: dealing with limits about what you can and cannot say)

Developers probably intend to embrace simple solutions at the start and only turn to more complex or nonstandard workarounds when they encounter a technical impasse. To get around the impasse, they have to invent creative “solutions” to get past the limitations. In some ways, these workarounds are just a necessary reality of coding. Still, without the same design constraints imposed by a UX review, I wonder if the simplicity bar for developer products is set too low.

If you work in developer docs, I’m sure you’ve encountered code that developers have created, which you must document, and thought, who allowed the developer to create this monstrosity? If UX designers would vet developer products themselves, it might be a different outcome. But without this UX filter, developers seem to have unlimited freedom to create nightmares of non-standard complexity.

For example, one product I document starts out with good intentions by using a semi-standard syntax (Jayway JsonPath) for parsing JSON feeds. But then a senior developer ran into some limitations, so he created a variable he arbitrarily called $$par$$ in the query syntax, which I then need to explain in the docs. Then for other scenarios not covered, such as with CDATA tags and attributes, the developer invented other custom syntax to work around limitations in the Jayway Jsonpath parsing library. The end result is a lot of custom syntax where you have to use standards in some places and custom syntax in other places.

As a tech writer explaining this to users, at some point I started to wonder whether this same kind of technical ugliness would have been developed if had we employed a UX designer to test and vet code designs with users, just like they do with user interface designs. Because we technical writers are generalists, we’re often bullied over by developers who say that the developer audience will understand and know how to use the code. And through this argument, the ugly code gets green-lighted for release.

TC jobs moving into developer domain

Bob Watson notes that when APIs are hard to document, it’s often a sign that your API is poorly designed and will experience trouble in the market — see If your API is hard to document, be warned. Let’s put aside issues of design and just agree that the developer domain is complex. It is likely complex for a number of reasons (not just the absence of UX designers). My larger point here is that tech writer roles are transitioning into the developer domain. We’re moving from GUIs to code, from mainstream end-user domains to developer domains because that’s where the complexity is. This transition is huge and significant and presents all kinds of new challenges that many tech comm professionals have never faced.

Why developers are writing more docs

So far I’ve argued that complexity has shifted more behind the scenes, in the area of engineering, and that’s where tech writers now focus. But this is not an easy domain for tech writers because tech writers are usually generalists.

Navigating the developer domain often requires an engineering level of knowledge. The information is so technical and specialized, tech writers (who are generalists) will have a hard time developing the content. The scenario where a technical writer can become a SME who understands the product with the same depth as the engineers is no longer common.

Because the needed documentation in the developer domain is so highly specialized, another huge trend is occurring: more engineers are writing and contributing to documentation.

Write the Docs as Evidence that Developer Docs Is Growing

As evidence that the developer domain is flourishing with engineering writers, just look at the emergence and growth of the Write the Docs groups. This group started out, in part, as engineers who write docs looking to connect and help other engineers writing docs. And this group has taken off in tremendous ways over the past few years.

In fact, Write the Docs, started in 2013, now has yearly conferences on 3 continents, meetups in 30 cities, and thousands of participants in the Slack channel. The group’s focus is on software documentation — not specifically developer docs but that’s what a lot of the presentations and members tend to focus on.

Some spinoff groups, API the Docs and Test the Docs, are even more focused on developer documentation. The only reason such a developer-centric tech writing community would flourish today is because tech comm has undergone a major evolution from end-users to developers as the target audience.

When you’re documenting systems for mainstream users rather than developers, tech writers can often amass a level of knowledge that makes them capable to write docs almost entirely on their own. But with developer docs and more complex products, it’s often beyond the capacity for tech writers to achieve this level of knowledge without full immersion in the system and more familiarity with programming languages, technical frameworks, and developer technologies on a deeper level. That deeper level of knowledge doesn’t come about without getting elbow-deep in code all day.

Shifts toward Markdown and docs-as-code

Because more developers are contributing to documentation (or in some cases, authoring the documentation entirely themselves), there has been a significant shift in authoring and publishing tools and processes. Much of the tech comm industry has shifted from XML to Markdown and docs-as-code tools because most developers find XML too cumbersome and tedious, and Markdown so easy.

For example, Microsoft’s developer docs were previously in XML, but they have since switched to a docs-as-code model. Check out Open Authoring – Collaboration Across Disciplines, by Ralph Squillace, for details. Microsoft is one of many companies making this switch. I also recently learned that Citrix’s developer docs just switched from an XML model to a docs-as-code model.

The shift toward simpler documentation formats is only one indicator of a deeper trend: When specialists engage in documentation authoring and publishing, they prefer to remain in their own specialization bubbles and won’t necessarily embrace anything sophisticated with authoring tools. So you might end up with a Markdown document or a Word document or wiki page and nothing more. (I’m short-selling the complexity of the publishing toolchains for docs-as-code solutions, for sure. But the basic format of topics is usually simple Markdown rather than a specialized DITA topic.)

The current predicament for tech comm

Enough with trends. This is the predicament where we find ourselves in: We are generalists suddenly surrounded in a context of specialization. How do we prove our value? How do we avoid becoming second-class citizens in developer organizations?

I think that in these specialist contexts, certain gaps open up. Technical writers can focus on these gaps to provide their value. In the scenario I’ve described, particularly when specialists start writing docs, at least three gaps open up. These three gaps involve the following:

(1) Authoring/publishing processes and tools (2) Knowledge/feedback about the user experience (3) Information usability and design

Let’s start diving into these areas. I’ll focus most of my discussion on the last bullet point (information usability), but these other two are worth noting.

Your reactions and input

You can see the responses (so far) here.