Confronting the fear of growing older when you're surrounded by young programmers

A recent article in the New York Times describes a retreat for aging tech workers in Silicon Valley, attended by some as young as 30. Here are a few excerpts from A New Luxury Retreat Caters to Elderly Workers in Tech (Ages 30 and Up):

In and around San Francisco, the conventional wisdom is that tech jobs require a limber, associative mind and an appetite for risk — both of which lessen with age. As Silicon Valley work culture becomes American work culture, these attitudes are spreading to all industries. … Their anxieties are well founded. In Silicon Valley, the hiring rate seems to slow for workers once they hit 34, according to a 2017 study by Visier, a human-resources analytics provider. The median age of a worker at Facebook, LinkedIn and SpaceX is 29, according to a recent analysis by the workplace transparency site PayScale.

In the retreat, held in a resort-like area in Cabo San Lucas, these “aging” tech workers adorn stickers on their bodies with negative thoughts about aging, and then they rip the stickers off and burn them in a fire pit. The author writes,

Others covered their chests and arms with stickers. “I fear being an old lady or man on the streets.” “I’m out of time to try something new.” “I feel increasingly invisible.”

The group members wandered silently, looking at each other and reading the notes. One by one, they peeled the messages off and burned them in a fire pit on the veranda.

One of the participants confesses he has trouble emotionally connecting with the same things younger people connect with:

“I feel like I’m just not getting it. I watch YouTube stars and all these things, and intellectually I get it, but emotionally I just can’t connect.”

The leader, Chip Conley, says that the irony is that “you actually are much happier in your 60s and 70s, so why aren’t we preparing for that?”

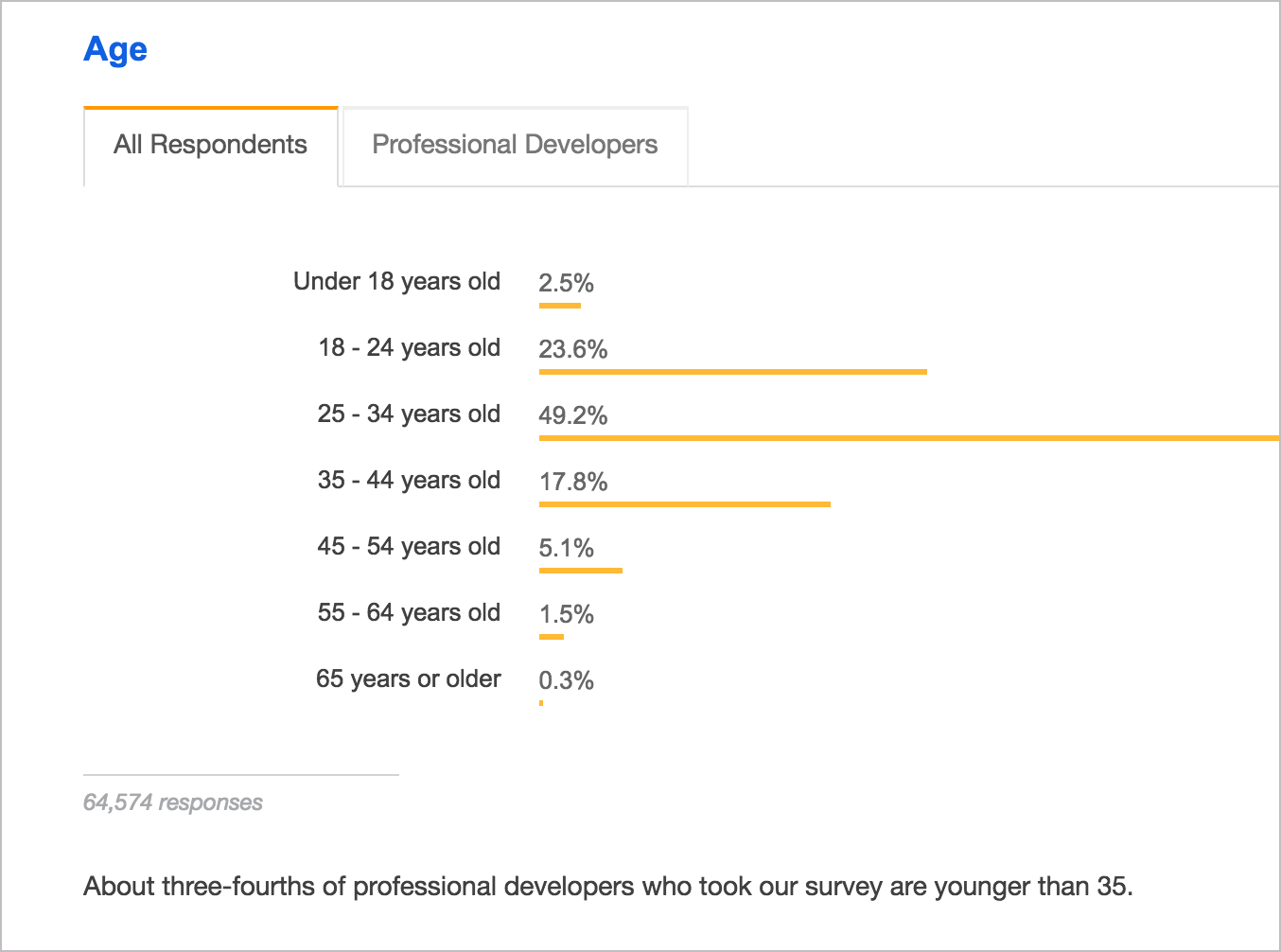

In a real sense ,this article about people as young as 30 experiencing fears of aging in Silicon Valley struck a chord with me. As laughable as it sounds, the article has merit, particularly when you’re surrounded by seemingly college-age demographics. In the 2018 Github Developer Survey, “about three-fourths of professional developers who took [the] survey are younger than 35.”

I’m currently 43, so in just two more years I’ll enter the 45-54-years-old bracket, where only 5.1% of people reside. That means that for every 100 developers I interact with, about 95 will be younger than me.

I can feel that I’m getting older. Here are a few experiences lately that make me think this way (in no particularly order).

For starters, I’ve recently suffered a few physical injuries from basketball that have caused me to wonder whether perhaps it’s time to either hang up my shoes or change my style of play. Recurring calf strains, a herniated disc, piriformis, capsulitis, impinged shoulder nerves — it can leave one feeling decrepit.

A few days ago we recorded episode 20 of the Write the Docs podcast. I couldn’t help but think our guest co-host looked right out of high school. I kept thinking, is he particularly young, or am I just getting older?

After my recent trip to the Symposium for Communicating Complex Information conference, while sitting at the airport en route back home, I was casually chatting with a conference attendee who asked if my profile picture on Linkedin was taken long ago — because I seemed to appear much younger in the picture. The picture was taken just 3 years ago.

In an attempt to cure snoring, for Christmas my wife pleaded for me to get a sleep study done. It was apparently the only thing she wanted for Christmas. It turns out I have a mild case of upper airway resistance syndrome, so I have been experimenting with a breathing machine at night. There’s nothing like sleeping with a nose mask on your face. One time I was reading a book called The Gift of Years: Growing Older Gracefully (a gift from my late father) while wearing the mask — a complete picture, that moment.

I also bought a ring-band device called Go2Sleep. It’s little plastic ring you wear while sleeping that tells you your heart rate, oxygen level, apnea events, amount of tossing and turning, and other details. It’s a nifty, unobtrusive device, and I find myself deeply curious about some of these health details. When my heart rate drops below 50 or my oxygen level gets dangerously low, is it a sign of something? Why am I suddenly so obsessed with these health details?

I have given up on trying to text with my thumbs with any speed. Instead I use MightyText on my computer and fake it. I try to respond more quickly to emails, texts, and other messages, because in the back of my mind, I think this helps me appear young and responsive. But also, I will often forget entirely about the message when it slides past the first screen of my email inbox. Unfortunately, responding in the moment fragments my attention and makes me more unfocused. I think I need the flow that comes from undistracted immersion.

When I read articles on websites, I regularly hit command+plus a few times to increase the font size a bit so that it’s readable. The other day I found myself actually changing the font on a site through the developer console because the author’s font selection simply bothered me. How picky I have become. Am I now an old style grouch?

Of my four kids, my oldest, now 18, is preparing for college. It seemed like only yesterday that she was riding her scooter in the park and going to third grade. My wife and I are both overly excited about her prospects for college, and it’s obvious that we both want to be in her shoes — a young undergraduate just entering college for the first time again, the world wide open. I’m pretty sure we are more excited about college than she is.

Twenty years ago, I was most productive been 9pm and 2am. Now I am mentally brain-dead after 9pm. Mindless sports have become more enjoyable because they require so little but seem to mean so much, at least in the moment. The first few hours of the day, when I’m refreshed from a night of mediocre sleep, I am most productive. If I want to accomplish anything, that morning time is when I must do it. The rest of the day starts declining from afternoon onward.

This sense of aging worries me because the demographics at tech companies in Silicon Valley match up with the GitHub survey — so many people at my work looks like they’re still in college. I don’t want to become the old guy who is dismissive about everything, who isn’t open-minded, who constantly spouts negativity. I want to keep my mind young, plastic, quick, open, curious, and full of energy and willfully trying new things.

But already I find myself less and less interested in exploring new opportunities. I’m more settled in to the company I’m currently at, in my current cubicle and role, in part because it’s all so familiar, and because I’m fairly good at it. I’m tired of changing jobs from one company to the next. Does this mean I’m becoming less open to risk?

Part of me fears that as I age, the job market will close as hiring teams question my “team fit.” How else do you explain it when people who possess experience and skills get rejected from positions in which hiring managers are half their age? I’m not sure how to address the paradox of acquiring wisdom through experience but also staying open-minded when experience after experience has taught me that certain conclusions are usually inevitable. But one must find a way.

Overall, I’d like to know how to stay young, even if my mind and body grow old. I don’t want to my brain to slow down or become too fixed/set in my ways. I think the key must be to keep learning, as learning will likely keep the neural pathways in the brain flexible and re-shapable (however the brain works). Everyone champions the learning mindset, especially in the ever-changing technology space.

The question is how you build learning into your day without sacrificing productivity. I’d be happy to sit at my computer going through tech tutorials and reading journal articles and for hours on end, but people expect results; they want documentation actually written. At night, my kids and family (and the dishes) tend to consume what energy I have left in the day. So where do I find the time for deep, immersive learning that will keep my brain young?

I don’t mean to sound gloomy here. Many people I know in the field have many more years (and experience) beyond me, and will laugh at my own thoughts about aging. The irony, as Conley points out, is that at my age, I’m benefitting from the many years of writing experience I’ve already logged. Figuring out the right direction or strategy on a project is no longer a guessing game. I’m rarely wrong about my doc decisions. If I want, I could probably coast for a decade. Performing my job doesn’t stress me out, and I still hit regular home runs on projects.

But right now, typing this, my brain is tired (even after multiple cups of coffee during the day). It’s only 9:30pm and my neural pathways have become salty potato mush. Will my brain-dead hour slowly stretch earlier and earlier until my productivity time fades out? Will there come a time when my peak daily productivity time lasts about an hour?

I might not pay the $5,000 to go down to Cabo San Lucas for Conley’s emotional retreat, but I do think I need to deal with this fear of aging. It seems one of Conley’s key points isn’t to find a way to become young again, but to discard this notion that with age comes decrepitude.

Picasso once said, when asked why his earlier paintings were dark and formal whereas his later paintings were colorful, vibrant, and more youthful, that “It takes a long time to become young.” He was perhaps commenting on difficulty of returning to honest, spontaneous, and authentic expression despite the many internalized social norms and standards. Though his comment focused on art, Picasso’s perspective obviously has many other applications. It suggests that youth isn’t a period in life but rather a state of mind, and one that takes time, perhaps many years, to achieve. The young can be old and the old can be young — biological age is irrelevant.

Following his advice, to return to a child-like state, I think you have to un-learn what you’ve already learned. Or rather, you have to acquire new learning that challenges or subverts what you thought you already knew. This is the paradox of it all — learning keeps you young, but only if you can unlearn what you’ve previously learned. That sense of awareness about yourself and life rarely correlates with age.

Tip: To read more on this topic, see How to encourage risk-taking and idealism without falling prey to cynical attitudes born from experience.

Here are a few short survey questions to gauge your thoughts on this topic. You can view the ongoing results here: