*How* you write influences *what* you write — interpreting trends through movements from PDF to web, DITA, wikis, CCMSs, and docs-as-code

Trying to pin down noteworthy trends

During the last holiday break, I was sitting inside a cozy hotel room in Red River, New Mexico, on vacation but also thinking about tech comm trends. Every year, as one year ends and a new year begins, bloggers and other writers address trends for the coming year. Especially since this topic has always gathered more hits than other posts in the past, I wanted to write a new post about trends.

I found two recent research efforts about trends to be the most noteworthy: Saul Carliner’s Tech Comm Census results (published in Dec 2018 STC Intercom) and Scott Abel’s Benchmarking Survey (also summarized in the same Intercom issue).

Saul Carliner set about gathering a “Tech Comm Census” by gathering responses from 60 questions covering seemingly every facet of the technical communicator’s work life. He partnered with the STC to promote the survey and gathered 676 responses. The results are interesting and encouraging, especially the finding that 70% of technical writers are satisfied with their job. At the same time, the survey seemed to miss many of the trends I’d been seeing within the developer doc space around Write the Docs and docs-as-code tools. I felt like the survey’s results only partially represented my tech comm world.

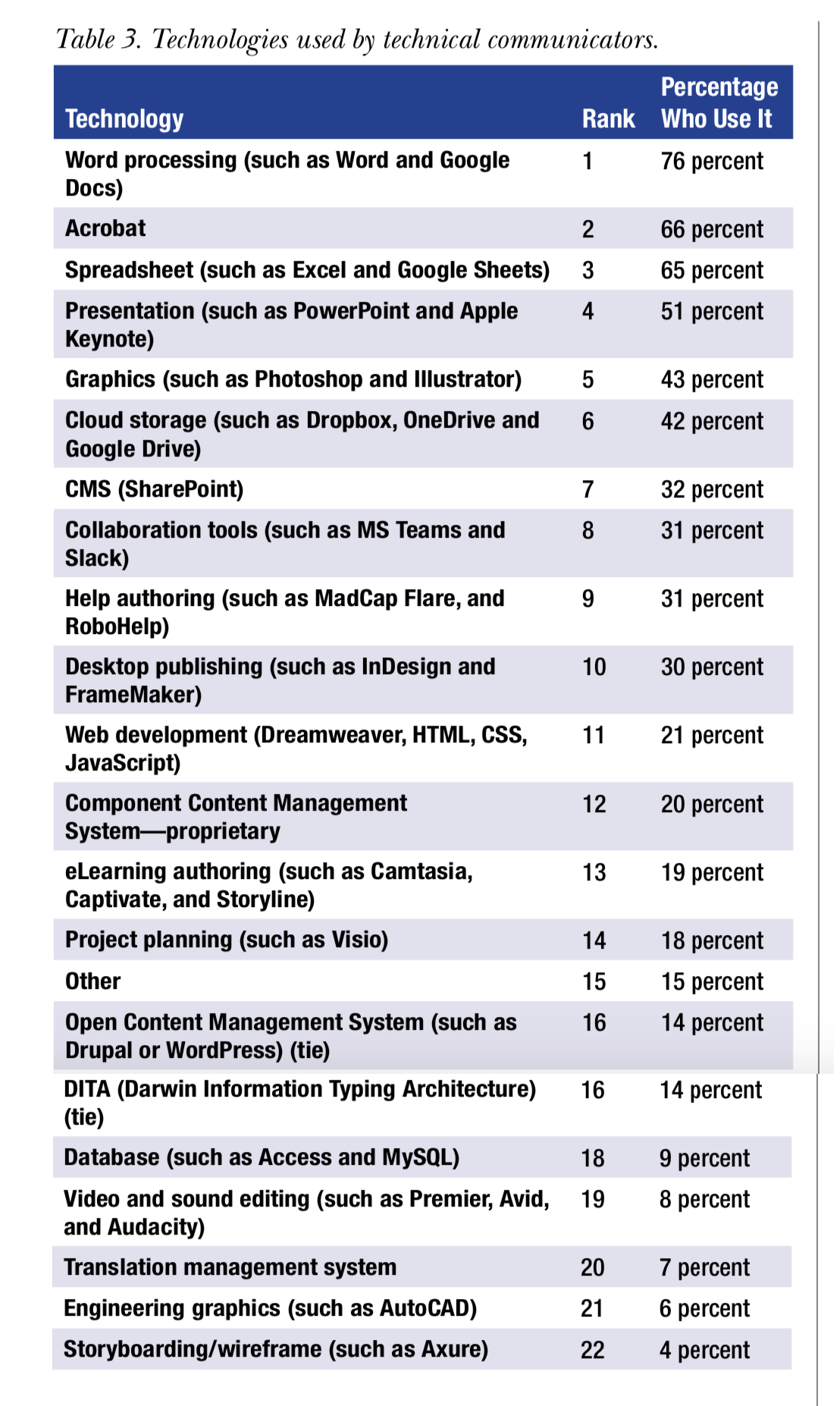

The census reports only generally about “technologies” that technical communicators use, noting that “The most widely used technology by participants was word processing, used by 76 percent of participants. Next were Acrobat (66 percent), spreadsheets (65 percent), presentation graphics (51 percent), and graphics (43 percent).”

All tools (authoring, graphics, storage, planning, etc.) are lumped together, so it’s hard to sort them out. The table looks like this:

If you narrow that down to actual authoring tools, it looks like this:

- Microsoft Word or Google Docs: 76%

- Help-authoring tools: 31%

- FrameMaker, Indesign: 30%

- CCMSs: 20%

- DITA: 14%

Saul acknowledged that his survey did not segment based on audiences tech writers write for, such as engineering versus non-engineering audiences. Another limitation was that 591 of the 676 survey respondents were STC members, which wasn’t necessarily representative of the tech comm profession as a whole (see “A Note from the Guest Editor,” Dec 2018 Intercom).

Scott Abel’s Technical Communication Industry Benchmarking Survey (summarized in an Intercom article titled Survey Reveals Top Tools, Trends, and Technologies in Use in Technical Communication Teams) gathers information about tools, trends, technologies, and other details from 600+ professional technical communicators. No details are provided about the intended audiences the respondents write for (e.g., engineering vs non-engineering audiences), but I assume the demographics of both authors and audiences generally align with those who read The Content Wrangler and attend conferences such as Information Development World, which tend to focus on content strategy, enterprise content re-use, multi-channel publishing, localization, chatbots, and more.

Scott’s survey does actually include some API-related information. He found that “Fifty-eight percent of technical communication teams surveyed say they currently document APIs; 10 percent plan to in the future.” One challenge tech writers face in documenting APIs is “using software tools not optimized for ease-of-use or writing efficiency, and lack of experience,” Scott writes.

These responses about APIs are more relevant to my tech comm world, but they don’t go far enough into dev docs for my interests. As with Saul’s census, Scott’s survey hardly mentions docs-as-code tools or workflows. In both surveys, communities like Write the Docs aren’t mentioned, and other more developer-oriented topics are left out, such as how writers integrate with engineering scrum teams, whether writers auto-generate the OpenAPI spec or manually create it, whether docs reviews are conducted like code reviews, and so on.

Granted, just because I’m interested in these more developer-documentation-related topics doesn’t mean general tech comm surveys need to cover it. I just feel that some of the more interesting trends, especially related to the space I’m in, were overlooked. There are actually some fascinating trends taking place that I feel should have been noted.

What perplexed me most was to see Adobe FrameMaker and Microsoft Word used so prominently. Scott writes,

While 47 percent of technical communication departments use Microsoft Word as their primary authoring tool, tech writers use a wide variety of software tools. For example, in tech comm departments that create multi-channel, multi-language content for highly configurable products or services, Adobe FrameMaker is the authoring tool of choice.

Twenty percent of all technical communication teams surveyed say they create documentation using the Adobe Technical Communication Suite (a package of several Adobe products, including Adobe FrameMaker, bundled into one solution). Twenty-nine percent of technical writing teams use FrameMaker as their primary authoring tool; while the majority (90 percent) of those teams also sometimes utilize sister products—Adobe Illustrator and Adobe InDesign—to help them craft technical documentation deliverables.

Other software tools technical communication teams use include Author-it (17 percent), Oxygen XML Editor (16 percent), Oxygen XML Author (14 percent), Arbortext (9 percent), MadCap Flare (5 percent), and Oxygen XML Web Author (3.5 percent).

Although the tools numbers between Scott and Saul’s surveys more or less align, I knew these numbers didn’t represent the tools used in the developer doc community. In fact, one recruiter for API doc positions told me that listing FrameMaker on your resume is a sure way to red flag yourself out of the position.

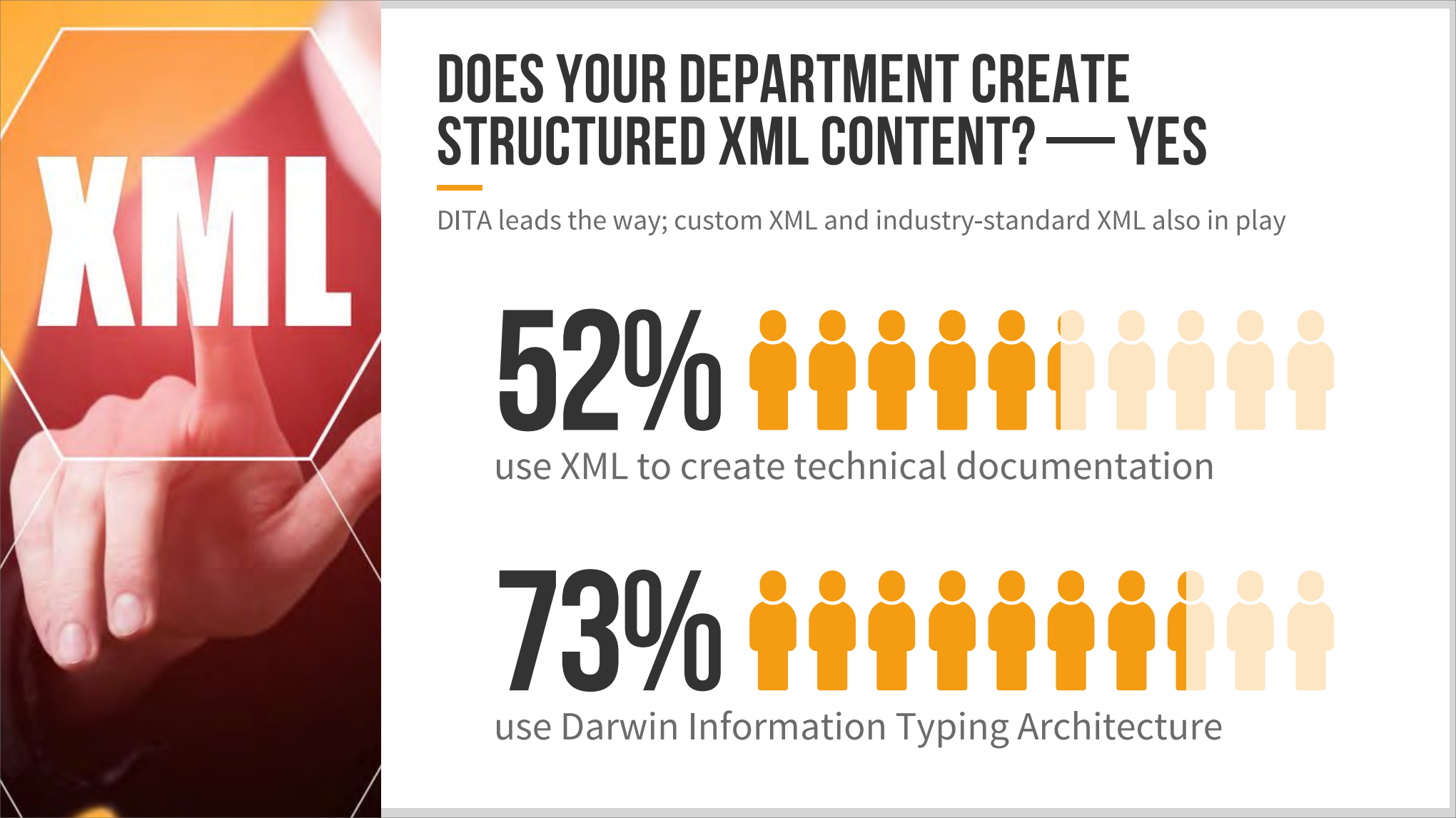

Upon closer reading of the Benchmarking report’s results, I realized that the report doesn’t say how many are actually using XML tools — the report says that for those who answered “Yes” to using XML, 73% are using DITA.

We don’t know how many out of 600 answered Yes to using XML. It could be six or six hundred. Likewise, the statistic about FrameMaker’s usage at 29% qualifies that segment only to “tech comm departments that create multi-channel, multi-language content for highly configurable products or services.” How many departments like this are there? Again, six or six hundred?

At any rate, the tools usage reported by the Benchmarking survey isn’t too far off from previous WritersUA Tools surveys, when Joe Welinske used to measure tools used. In 2014, WritersUA found around 52% of writers (199 out of 382 respondents) used FrameMaker (2014 WritersUA Tools Survey). At some point, Joe stopped measuring tool usage.

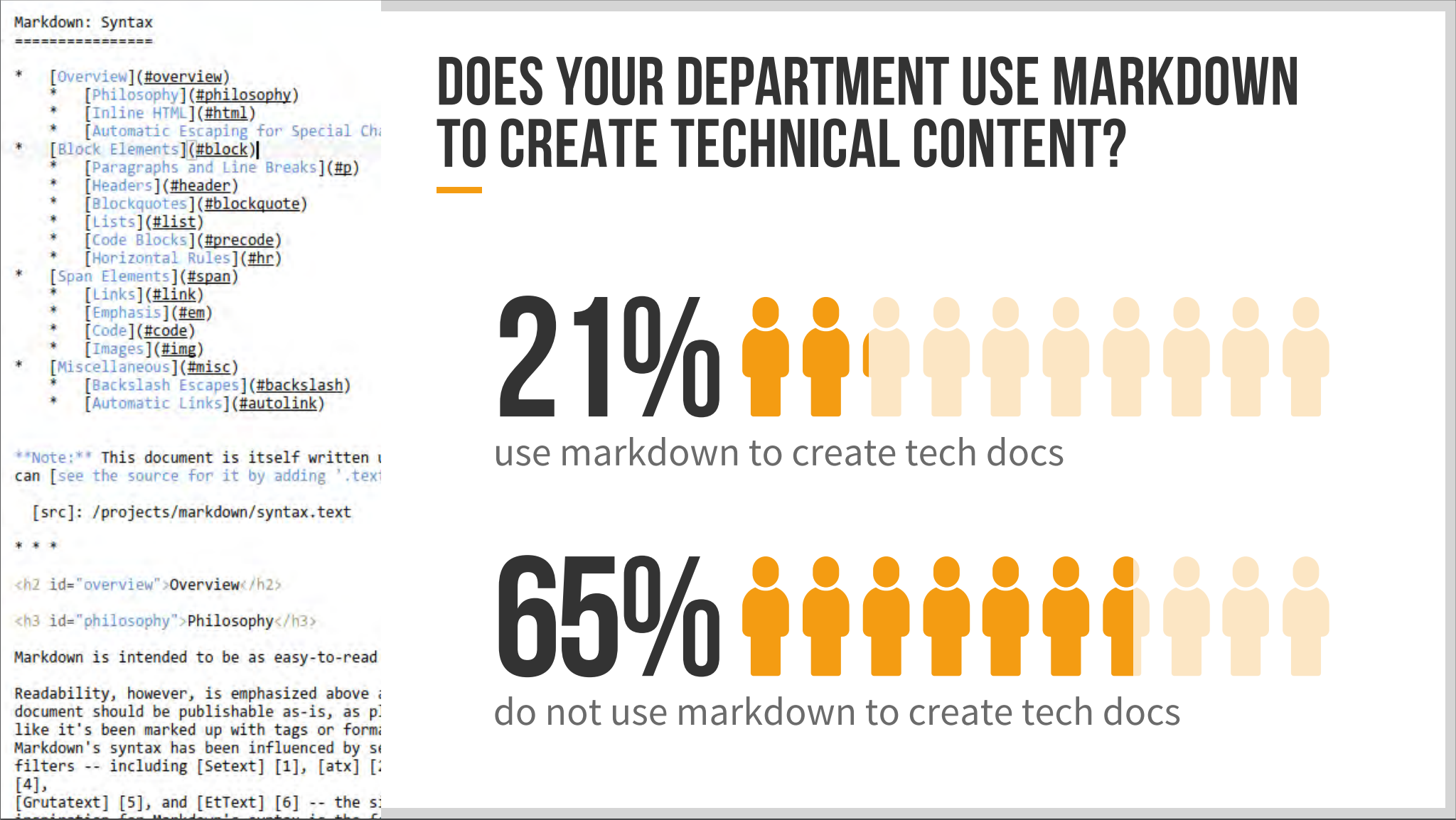

Scott’s survey does find that 21% of technical communicators use Markdown to create docs:

This statistic doesn’t seem pre-filtered and also fits in with my larger interests related to API documentation.

Gathering data for another perspective

I wanted to rebut some of these trends (at least as far as their representation of the dev doc community), but I didn’t have any data. You can’t write a post that says a particular survey isn’t representative without supplying alternative evidence. So I decided to create my own survey, filtering respondents down to just those writing developer documentation only because that’s the segment I’m interested in.

I came up with 50 questions specific to dev docs but also addressing some of the other questions (e.g., PDF, video, localization) that would cross-check the results against the other surveys. I publicized the survey on my blog and newsletter and gathered about 200 responses over the course of two months.

You can view the results here. As the survey is still open, the responses are still coming in. I’ll close it on March 1. Here are some highlights as of Feb 19, 2020.

Primary authoring tool

- 23%: Static site generator tools

- 13%: Internally built tools

- 13%: Wikis

- 10%: XML authoring tools

- 8%: HATS (e.g., Flare, Author-it)

- 8%: MS Word

- 2%: Adobe FrameMaker

Most common editor:

- 28%: Visual Code Studio

- 14%: Atom editor

- 11%: Sublime Text

Follow docs-as-code:

- 55% yes

- 23%: somewhat

Most common source format:

- 40%: Markdown

- 14%: XML

- 14%: HTML

- 5%: Asciidoc

- 3%: rST

Other findings:

- 70% manage their content in version control such as Git.

- 73% don’t localize.

- 62% don’t usually generate PDFs

- 25% use the same code review tools that engineers use to review software code.

- 66% are not former engineers nor did they have a highly technical role previously.

- 83% of the respondents usually document an API, and 58% of the time it’s a REST API. 48% use OpenAPI spec for this.

- 43% feel the most affinity to WTD, and 13% to the STC.

- 76% are satisfied with their job.

Focusing on tools — ephemeral shifting winds only?

There’s a lot that one could focus on these survey results, but I think the most salient feature, or one that catches my attention, is the prevalence of static site generator tools. Clearly, with 23% using static site generators (SSGs) and only 2% using FrameMaker, this represents a major shift. Surely this merits more exploration.

One immediate objection might be this question: why focus on tools? Aren’t tools like shifting fashions? Like the style of jeans that changes from one decade to the next.

This is why academics dislike tools — tools are ephemeral. One day it’s Tool X, tomorrow it’s Tool Y, and next week it’s Tool Z. But what matters is the content and the theoretical foundations that determine what we write and how we present it to the user, right?

Sure, for the most part, I agree that tools are like the basketball player’s shoes — undoubtedly not as important as the style of play, not as important as the plays that teams run or the strategies players apply to win the game.

But here’s the thing. To some degree, how you write influences what you write. The how includes tools and the workflows you use with those tools.

To make this argument, I’ll survey the doc tools technical communicators have used over the past 50 years or so and comment generally on how those tools influenced the user experience. This will be a birds-eye view with many general observations as I move from PDF to web, then to XML, wikis, CCMSs, and finally to docs-as-code.

Warning: At this level, I will make broad generalizations and try to connect trends together based on shaping forces and challenges that drive the evolution. At this level, it will be somewhat speculative but hopefully still informative. This tour through tool usage looks somewhat like this:

Note that this timeline isn’t necessarily a progression — all of these tools are still in use to varying degrees. And some of these categories overlap.

Before the web, there was PDF

Before the web, tech writers created PDFs to distribute content to users. PDFs encouraged long-form, book-like content. In general, readers were expected to move linearly through content from beginning to end.

John Carroll busted that myth when he observed how people actually used help. They didn’t read from start to finish, like a book, but rather jumped around from task to task depending on their needs. (See How to design documentation for non-linear reading behavior.)

Even so, the book paradigm encouraged sections and chapters rather than individual topics, and when tech writers started transitioning to the web, they migrated their books to web formats by auto-bursting them at specific breakpoints, such as by chapter or heading.

Web encourages topic-based authoring

With the web medium, topic-based authoring took the spotlight, and tech writers began breaking up their content into small, standalone chunks online (like articles). The transition from book-length authoring to topic-based authoring introduced many new challenges. For content auto-bursted at breakpoints like subheadings, the chunks often didn’t make sense alone.

Mark Baker’s Every Page Is Page One is a reaction against these chunks that don’t make sense alone (see Topic Chunking and The Broken Alarm Clock). When you encounter help content that seems to require some other starting point to make sense, leaving you scratching your head at your starting point without the proper orientation to make sense from your entry point, the docs fail for that user. Mark said every page should sufficiently orient the user as if it were the user’s first entry point in the docs.

Help authoring tools proliferated in the early days of the web, and writers became good at single-sourcing chunks into ever-increasing efficiencies. But here’s my point: the tools and medium we used to create content influenced the content itself. This shift in tools and publishing outputs transitioned writers from creating book-length content that required more sequential, linear reading to more standalone topics that afforded non-linear reading behaviors.

XML/DITA enforces structured authoring

Soon XML started to appear on the scene, which was an evolution from SGML markup. XML imposes a consistent structure on content, requiring users to conform to rules defined in schemas and other definition documents. The most widely adopted XML format in the U.S. is DITA (Darwin Information Typing Architecture). Donated by IBM to OASIS in 2005, DITA attempted to provide an industry standard for XML in tech comm. Writers didn’t need to fuss about creating their own transformations of XML into different outputs but could tap into a standard that tool vendors would support in robust ways. Writers could focus entirely on content (conforming to the XML schema) and let the tools transform it into beautiful, readable outputs.

While DITA doesn’t outwardly enforce a design pattern in docs, the atomic structuring of components with specialized topics (task, concept, reference) prompted writers to divide/fragment their content into individual units consisting of these types. DITA does let you create maps that assemble these task, concept, and reference units into more complex displays, but many DITA writers simply use a 1:1 relationship between the source and the display. As a result, the display from DITA projects often ended up with sometimes hundreds of tiny topics, some as small as one paragraph. (See Does DITA Encourage Authors to Fragment Information into a Million Little Pieces?)

DITA is one of the most polarizing topics in tech comm, with many conflicting views on its information architecture and design patterns. I recently listened to a presentation (internal) from a tech writer who was providing guidelines to engineers on writing. He had compiled an attractive wiki with many excellent points. However, what appeared to be a massive trove of information with many pages turned out to be much smaller than it initially seemed. Some pages consisted of just one paragraph. He strung these pages together into larger navigation maps. You had to click around a lot to read it all. He said the design principle built on the principles of DITA.

Again, here we see that how you write influences what you write. When you write following an XML schema like DITA, this influences the output and display to the user. Tools and the technologies we follow in authoring and publishing aren’t invisible, non-influential components in the writing process.

Wikis and reciprocal feedback loops

DITA and XML are still popular formats, especially because larger systems (component content management systems, CCMSs) require structured content for processing and manipulation. But it didn’t take long for people to realize a major limitation to XML: it’s too cumbersome and complex to really scale beyond the tech comm team. What if you want more people to author and contribute? As crowdsourcing models started to gather attention, with sites like Wikipedia taking off, wikis started to become a popular format.

The promise of wikis was to allow docs to be crowdsourced by a community of disparate people (not necessarily tech writers) all collaborating together on content. Some felt that wikis might even eliminate the need for tech writers altogether. If you just created a wiki for your product, users would write the documentation for you. A thousand users each contributing one paragraph might create all the docs you’d need. Tech writers would act as curators, managers, and organizers of content rather than the primary authors.

Wikis provided an interesting platform. During the heyday of wikis, I was smack in the middle of a volunteer community and publishing content on MediaWiki. It was cool to monitor updates across the site and wonder about the identify of all the contributors making edits. Wikis introduced a more collaborative platform than any other before (and one that has won out as the default platform for internal docs).

One academic, Guiseppe Getto, who engages in iFixit projects with students, noted that wikis provide a “reciprocal network” that creates constant feedback loops in writing. He referenced Latour’s Actor-network theory to describe a model where the tool one uses literally becomes an actor in a network of influences that produces a result.

Guiseppe writes,

What I noticed when my students were working in the Technical Writing Project is that the tools they used (literally, from the tool kit provided by iFixit) and the wiki technology they used to write their guides profoundly impacted their writing process.

For example, one writer adds content on a page. This content is modified by another writer (creating a feedback loop); then another writer modifies this modification (creating another feedback loop), and so on. Content is never fixed but continues evolving as more feedback loops set the content in motion. (See Reciprocal knowledge networks and the iFixit Technical Writing Project – Conversation with Guiseppe Getto.)

Again, wikis provide evidence that how you write influences what you write. Guiseppe says that when students simply searched Google for information and wrote in more static formats, their content and writing experience was notably different than when writing in the immersive feedback loops of wikis.

Alas, the promise of wikis didn’t win over the tech comm community. Even as I had 60+ volunteers engaged in my projects, I abandoned wikis because the efforts didn’t pay off. I spent just as much time managing content and people as it would have taken to write the content myself. More than anything, external contributors lacked access to the right information sources and people to create the needed content. External contributors who added information post-release mainly just noted misspellings and broken links — processes that can be automated through verification scripts. (See My Journey To and From Wikis: Why I Adopted Wikis, Why I Veered Away, and a New Model.)

CCMSs re-use content across the enterprise

Another player in the landscape of tech comm tools is content management systems (CMSs) and component content management systems (CCMSs) — the latter is more common for tech comm. This is a broad category that might encompass both XML and wikis but which tends to stand alone as well. Content management systems were championed as ways to maximize the use of your content across many different channels and outputs, leveraging the content for the many outputs that the content could serve. Content management systems comprehensively track assets, noting metadata for each topic including the author, last modified date, instances where the content was (re)used, and more. CCMSs automated publishing across many different channels, leveraging your content as a treasured asset that would get maximum use and re-use. The seminal text for this category is Ann Rockley’s Managing Enterprise Content: A Unified Content Strategy.

With social media requiring more content, the CCMS would let you create one nugget of content that could be re-used not only in docs, but in marketing pages, white papers, blog posts, eLearning, and other channels. Without a CCMS, you would end up either clumsily duplicating this content through copy/paste, or it might become inconsistent with conflicting terms and concepts or other details if teams across the enterprise worked in silos. Instead of managing the content in one place for all channels, companies without a CCMS would exhaust themselves recreating the content in bespoke ways for each needed channel, or else the company would let the wells run dry by only using the content in one place. “Intelligent content” is all about re-using content more efficiently across the enterprise for all the needed channels.

How did the CCMS influence what writers wrote? Knowing that your content must stand true in many different outputs, it caused writers to think more broadly across the many different channels the content might appear in. Changing one component might require more comprehensive analysis for all the places it was re-used, and this system was intended to be a source of truth for many different groups (tech docs, marketing, support, and other groups) to share and leverage content. In this way, CCMSs tried to create more coherent and integrated content across the enterprise, not just for the tech comm group.

CCMSs are still widely used, especially by large organizations, but the cost and complexity of their implementations limits their popularity to the companies that can afford them. For example, a CCMS can easily cost half a million dollars to implement. This is clearly a tool for large enterprises. It takes a special corporate culture to manage docs in a centralized way across many different organizational boundaries and groups, and many CCMS implementations fail. In an era where independent, autonomous agile groups are becoming the norm, with no centralized doc group or authority, the enterprise CCMS is difficult to support. (See Autonomous Agile Teams and Enterprise Content Strategy: An Impossible Combination? and my related podcast with Cruce Sanders.)

I’m not saying that small agile teams following Scrum ended CCMS proliferation, as all of the tools I’ve mentioned are still in use today to varying degrees. However, the trend toward integration with Scrum teams encouraged writers to be more embedded with engineers. On many of these Scrum teams, which act somewhat autonomously, like startups within larger companies, and where roles are more multi-faceted and less defined, many engineers also played roles as writers, or “documentarians” as some call them. This brings us to our last category: docs-as-code.

Docs-as-code and the promise to unlock collaboration with developers

The information economy encouraged more companies to deliver their information as a service through APIs, and as such more engineers started playing documentation roles with their APIs and other code. Naturally, developers used many of the same tools they used for code to write docs, leading to the “docs-as-code tools.” Markdown formats rose in popularity, as this format was readable in plain text (and in the same editors developers used to write code). Additionally, Markdown worked well with version control systems like Git to show what changed from one commit to the next (diffs).

Developers like to create tools, and they started creating their own document generators to compile the Markdown pages into templates as a website. The hundreds of static site generators on StaticGen are a testament to the lively development in this space and the complete freedom to innovate — in contrast to the tightly constrained schemas of XML. A developer might decide to fork an existing tool to create a new version, scratching an itch they might have for some new feature. Or a developer might take an existing tool and implement it in their favorite language (React, Go, JavaScript, Python, Ruby, Rust, or more).

Doc-as-code tools use the same software processes as software developers use to develop code, so beyond the text editors to write content in plain text (instead of rendered through a visual editor), doc reviews often use code review tools, files are managed through version control such as Git, and deployment models follow a CI/CD (continuous integration / continuous deployment) model, where you simply push content to a branch in Git to kick off an automated process that builds your content from the server.

How has docs-as-code influenced what content we write? With no XML schemas to follow, Markdown follows a more free-form format (for better or worse). You can mix tasks, concepts, and reference more seamlessly based on the dictates of the content rather than the dictates of the schema. You can more easily paste in code examples, since you’re just pasting code in text editors, and the code will usually be syntax-highlighted (through the static site generator) to make it more easily readable. (Try pasting the same code into a visual editor like Microsoft Word and you’ll see the problems it creates.) This text-based format surely encourages more sharing and use of code samples in docs, just as Latex formats enabled more efficient authoring and sharing of equations — see An Efficiency Comparison of Document Preparation Systems Used in Academic Research and Development.

But the promise of doc-as-code is not just to provide an easy platform for developer docs. The promise of docs-as-code, and why tech comm groups embrace it, is to unlock collaboration with developers by meeting them in their tools space and workflows. When you embrace the developer’s workflow (contributions through pull requests, management of features in version controls, builds from the server, open formats and templates that build the content, and more), you create a collaboration between developers and tech writers in more tightly coupled ways than was possible with proprietary, licensed-based tools following XML schemas. Docs-as-code tools unlock the potential for more developer collaboration with docs, which then influences the content we produce — simply put, the content includes more developer contributions and input.

Of course, the degree of collaboration depends on how much you push for it. You can use docs-as-code tools in a completely isolated way, not even extending permissions for developers to contribute pull requests for your content (similar to how you could also use a wiki for just one author). But doing so blocks the primary benefit of doc-as-code tools. The opportunity for collaboration with developers is available to exploit in unprecedented ways. (At the same time, collaboration with marketers becomes hampered.)

Conclusion

Returning to my earlier question, are tools just passive receptors of content, or are they actively influencing the content we write? As I’ve painted broad brushstrokes from PDF to web, XML and DITA, wikis, CCMSs, to docs-as-code, I’ve described how these tools are more than passive foundations for content but rather act more prominently to shape the kind of content we produce. As a thought experiment, consider what your output would look like if you switched from one system to another, delivering through PDF instead of docs-as-code, or structuring your content with DITA instead of a wiki, or integrating with a CCMS, and so on. As you contemplate these transitions, it might be more evident that how you write influences what you write, in addition to shaping other aspects of the user experience.

Overall, there isn’t really a “best” approach, nor necessarily a progressive evolution from one toolset to the other. However, we should recognize the particular strengths that a tool or technology has and capitalize on those strengths. If you’re using a CCMS, maximize your content’s use across the enterprise, breaking silos and department boundaries for content. If you’re using a wiki, both seek out and welcome as many reciprocal feedback loops as possible. If you’re using DITA, maximize re-use and intensify the focus on content rather than tools. If you’re using PDF, create beautiful story arcs with more in-depth narratives for your content. If you’re working in docs-as-code model, collaborate as much as possible with engineers. Each of these advantages can be preferable in different tech comm scenarios. Where we go wrong is not understanding the ways our tools shape content, or failing to exploit the advantages available to us by virtue of our tools.