Reflecting seven years later about why we were laid off (Part IV)

Destroying [changing] the stretched-thin model for content design

I want to dive into this topic a bit deeper with some contrasting perspectives. Jonathon Colman recently gave a preview of an upcoming presentation called How we destroyed content design, planned for the Design and Content 2020 conference in July. Jonathan works for Intercom and is currently based in Ireland. The description of Jonathon’s talk is as follows:

Most content design leaders stretch their teams to cover many products at once, or sometimes 5-10 or more. This unintentionally causes the team to constantly switch context, drive less product impact, lag in their career development, earn less pay, and ultimately burn out and leave… only to repeat the cycle elsewhere. This is normal… but it shouldn’t be.

Content designers work on UX writing and a host of other content deliverables for the product (such as social media, white papers, website copy, email campaigns, etc.). (For more on UX writing, see UX writing processes and considerations: WTD podcast episode 28.) Jonathan says that in big tech companies, many content designers are limited to writing-related roles only and so are spread across many different product teams, often between 6-10 different products or more (although some have 20 projects and higher). As a result, their engagement with product teams is much shallower. They can’t ramp up as product experts or play more influential roles on these teams. Their hands are tied from deeper engagement precisely because of the many different product teams they are working across.

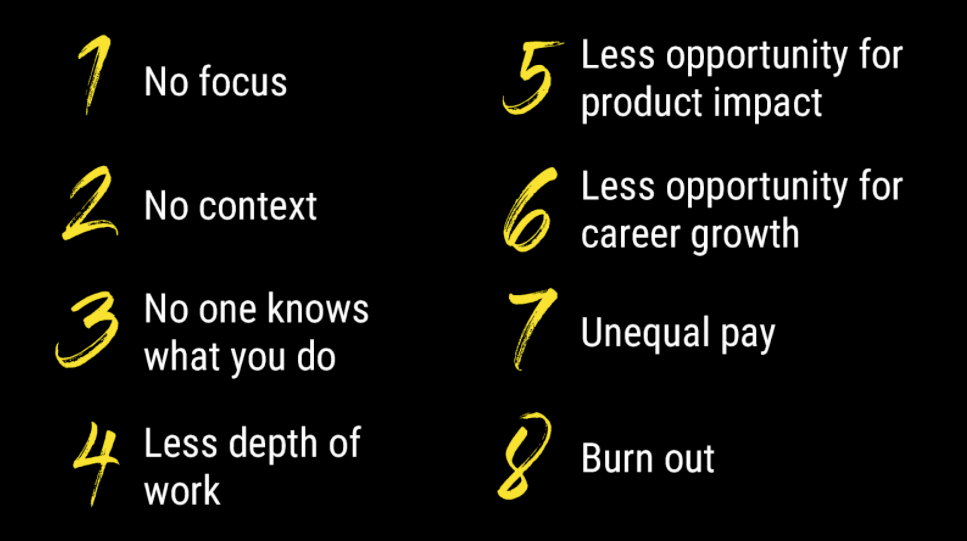

Jonathan lists out the problems that result from this multi-project allocation model:

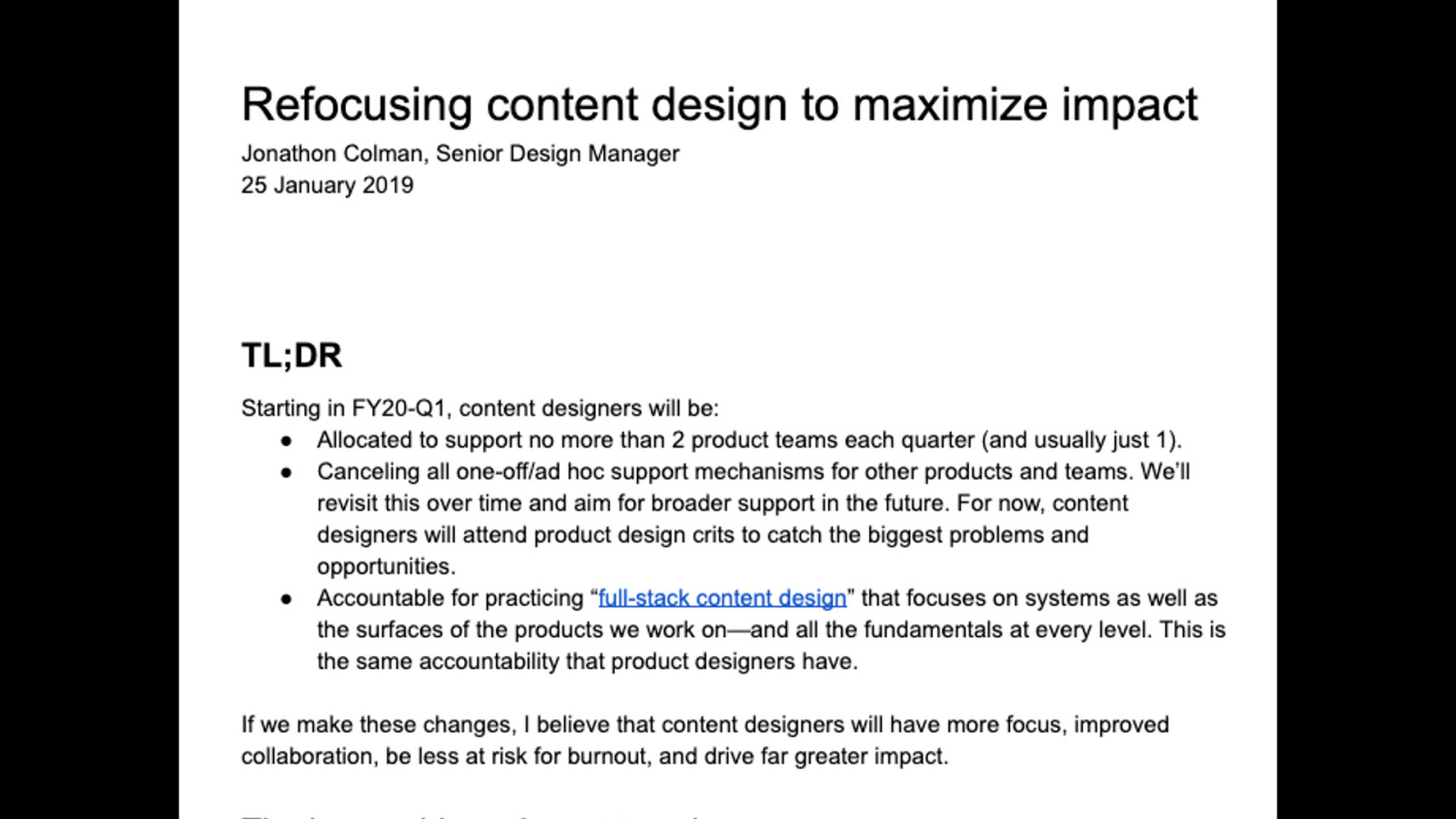

In a radical change to this model, Jonathan says they implemented a new change to their way of working at Intercom. As an experiment, they changed the load so that content designers would be “allocated to support no more than 2 product teams each quarter (and usually just 1).” They also switched to “canceling all one-off/ad hoc support mechanisms for other products and teams.” Each content designer would now be “accountable for practicing ‘full-stack content design’ that focuses on systems as well as the surfaces of the products that [they] work on – and all the fundamentals at every level.” Here’s a slide from Jonathon’s presentation showing the change:

Jonathon says they blurred the lines between product design and content design. This means content designers started doing more concept/system design, information architecture, and other tasks, not just UX writing. They had the bandwidth to work more deeply on problems, impact products, set product directions, get involved in roadmaps, and provide more solutions.

As a result, content designers worked with more focus and at a more specialized level. Instead of working on six different products, they worked on just one or two over a prolonged period of time (e.g., a quarter). They had more time, context, more integration into teams, and played roles as co-leaders. They attended all of the team’s rituals and often played a role in leading the team’s activities. They essentially played similarly influential roles as product designers and engineering managers. They were able to increase their efficiency, work at faster speeds, have more impact, and create more quality content.

Jonathon says this pivot also brought more focus to the role. The growth path for content designers has traditionally been to grow in scope, working across more and more teams. That wasn’t so fulfilling. The downstream benefit of this new hybrid role (content/product designer) is that because of their expertise, they became a leader in the product space and have more of a focused growth path. They can work across a single product life cycle in a deep way.

Deep versus brief immersion with projects

I find this pivot fascinating and it seems to confirm my previous experiences. In a post I wrote in 2020 titled Writing User-Centered Documentation, or, My Best Days as a Technical Writer, I argued that deep immersion on a product and team, especially with users, resulted in a much more fulfilling experience as a technical writer.

I do think if I were able to focus on just 1-2 products, I could have a more valuable impact. You can’t provide the deep value that Jonathon describes when you’re supporting 6-10 projects at once. When you are spread thin, the results are self-fulfilling: technical writers will add little value because within the time they’ve been allotted, only little value can be provided.

A recent experience illustrates some of these points. We recently received feedback from a field engineer who explained that the documentation for Product A was poor and needed to be fleshed out more. The field engineer noted that he learned Product A’s documentation was written by the product team rather than by the technical writing team. He mentioned that the documentation for Product B, where I had worked extensively on the documentation to clarify details, make the information step-by-step, and provide other improvements, was much better. He asked if a technical writer could be allocated to Product A to improve it similar to Product B.

The field engineer only saw our value because I had worked so much on Product B’s documentation and demonstrated our value. I remember spending months working on Product B. It took weeks just getting it to work, and I meticulously fleshed out all the steps in a clearly defined workflow. I fixed the sample app so that it would work, I explained the workflows and added many details in the reference documentation. I worked on this documentation for a long time (even over the holidays a bit). It’s one of the doc sets I’m most proud of.

But for Product A, I saw that the product team already had some documentation, and I was engaged in so many other products, I did a light edit only and published their docs. If I didn’t have the track record with Product B, would the field engineer have felt that tech writers could add much value? Or would he have assumed that technical writers play only marginal editing/publishing roles on a team? I’m assuming the latter. But to get him to believe we could add more value, we had to demonstrate this value first.

Here’s another experience that demonstrates how our perceived value is dependent on previous perceptions of value. An engineering team recently reached out to various groups to ask for suggested product improvements to Process X. I haven’t been working on Process X for probably 1-2 years, as I have been focused on other projects. Ideally, I felt like I should have been able to identify current developer friction points and suggest worthwhile product improvements for a better developer experience related to Process X. But since I wasn’t engaged deeply on the team, my ideas for product improvement for Process X were only cursory, and I in fact ended up not making any suggestions at all.

In the product team’s mind, this likely only solidified a less valuable role for tech comm related to Process X. We end up being perceived as documentation writers only, not as a more valuable role that would influence product design and improve the developer experience. This happens regularly — some teams ask for my feedback, but since I’ve only engaged cursorily with the product and users, I don’t have any deep value to add, and so I feel like it’s assumed that I am not capable of adding value in the first place.

The lesson is this: Others won’t believe technical writers can play more valuable roles unless technical writers establish some track record of adding deeper value. But if you’re stretched thin across 10 different projects without the ability to play a more valuable, impactful role on the projects, how will you persuade leaders that you’re capable of a deeper impact? I’m not sure how you break out of this cycle without somehow working overtime on one product to demonstrate the larger value you can play.

Reactive mindsets with technical writers

I also think that it takes a special kind of technical writer to engage at a deeper level. I’ve worked with many technical writers who are reactive to requests only. They often sit around until someone files a ticket with a specific doc request. Outside of this workflow (someone asking them to do something), they take almost no initiative to drive the work themselves. They don’t naturally explore support tickets, they don’t solicit or analyze user feedback, they don’t read deeply in product and business documents, and so on. Their approach to docs is to look for other teams to file tickets with specific documentation requests. They are reactive rather than proactive.

It’s probably this reactive technical writer that then ends up being allocated to many different products and teams in order to fill their workload. When a proactive writer comes on scene, this proactive writer is often lumped into the same assumptions and generalizations as the more reactive technical writers. It’s difficult to change these assumptions. I’m thinking back to Colleague 5’s story, where he encountered a CTO who openly admitted that he thought support was more valuable than documentation. In such a culture, can that technical writer ever hope for a reduced workload where he or she can play a more influential role, even influencing product design? I doubt it. And so the cycle continues. With little opportunity to add value, technical writers end up adding little value.

Jonathon’s story has some other gaps and issues to work out as well. I’m curious about how they managed “canceling all one-off/ad hoc support mechanisms for other products and teams.” Did they just say “no” to these other teams? How did the other teams manage the work on their own? Were contractors introduced to handle low-level tickets? And yet, without saying no, it would have been impossible to engage deeply with the 1-2 teams.

Overall, the value problem is complex – to provide more value, you have to reduce engagements on other projects to focus on 1-2 projects. But you won’t get this green light to reduce to 1-2 projects until you’ve demonstrated that you can add value.

Duplication of roles?

Another question I have about Jonathon’s role pivot is with duplication of roles. My sense is that executive leaders would look at this proposal (for tech writers to play hybrid content/product design roles) and wonder if this is simply duplicating roles within a team. We already have one product designer. Why do we need two? Is the existing product designer deficient in some way?

I remember a conversation I had with a QA team member long ago while I was working at ICS. At the time, we carpooled into work together because we lived near each other. One day we got into a discussion about how tech writers often play additional roles such as logging bugs from doing testing, among other overlapping roles. He pushed back on this entirely. He felt others were already dedicated to these roles, and as we expanded into these areas at the expense of documentation, we merely duplicated efforts that another team member was supposed to be doing. Why should tech writers log bugs? he asked. That’s QA’s role. He was happy for tech writers to stick to documentation only.

What my QA friend failed to understand is that writing documentation leads to developing product knowledge at a deep level, with unique insights from users. That knowledge has many applications beyond simply writing documentation. It can influence product design. To write really good docs, you have to accrue specialist knowledge. And when you have specialist-level knowledge about a product, you can play many more roles beyond documentation. In fact, it’s a waste of your expertise if you don’t leave the documentation page and engage in other dimensions of product development.

However, I admit that I’m actually not that eager to play a more dedicated product-design role. Jonathon’s presentation assumes that content designers want to expand beyond their writing roles and take on hybrid roles with product design. I can influence product design, but it isn’t necessarily something I want to do on a more official level. For example, I’m not sure I’m ready to lead the charge in saying “We need X feature” and then set about gathering user requirements, stakeholder requirements, business requirements, etc., and then wrangle in plans for development, resourcing, timelines, launch, adoption, etc. It’s kind of a lot. I’m much more resigned to distill user feedback and assemble a proposal on product direction that others can assess and execute on.

Also, in some ways Jonathon devalues the writing role by morphing content designers into product designers. Is it not enough to stick with content design? Do you have to be a product designer too in order to have value?