Imposing Order Versus Observing Order [Organizing Content 4]

It's easy to postpone organization. We begin writing discrete help topics, hundreds of them, and then try to group them together in a logical way. But here's where the problem starts. What does it mean for a system of organization to be “logical”? And how does the user navigate this logic we create?

Our system of organization partly determines the findability of the content. Without findability, we might as well not even write help at all. It's exactly this lack of organization/findability that turns so many users off with help content. When you click the help button and see an immense amount of folders and subfolders and sub-subfolders, all organized in seemingly impenetrable ways, it overwhelms users. They give up within seconds of their foray into the help.

As help authors, it's so easy to be seduced by technical distractions and overlook the content. We get drawn into styles and design, the look and feel of the help content, the single source rendering between print and online, the parallelism of titles, and the exacting conformity to our style guide. These technical bells and whistles distract us from more fundamental matters of content organization.

But content organization is fascinating. The way a help author lays out the help topics in a table of contents shows you more than simply a list of topics. It shows you how the author has wrapped his or her mind around the content, how he or she has chosen to shape order from chaos. It shows you how the author understands the user. And it shows you one perspective on the structure of the content.

Organizing the Periodic Table of Elements

Organizing a jumble of help topics into a natural, beautiful order that strikes clarity in the mind of the user is no different from the scientific urge to classify, to organize, label, and categorize. Nothing illustrates this better than the story of how Dmitri Mendeleev organized the Periodic Table of Elements.

Before Dmitri Mendeleev organized the table, he traveled extensively in Russia on trains flipping around a stack of cards that had the elements and their behaviors written on them. Sorting and resorting the cards, he kept searching over and over in his mind for a pattern, for a principle he could observe that would lend itself as the organizing pattern for the elements.

Sure, the elements had different atomic masses. The atoms of some elements were heavy; others were light. But the atoms also displayed other behaviors. Some elements were friendly with other elements; other elements were shy, like loners.

This seemingly random array of heavy, light, shy, friendly characteristics made it tricky to organize the content in a logical way. What was the right way to organize these 90+ elements? What underlying logic explained the element's natural classification and hierarchy?

The right system of organization finally came to Mendeleev in a dream. A sudden flash of insight, not an order he created, but an order inherent in the content he observed. He finally saw the elemental grid.

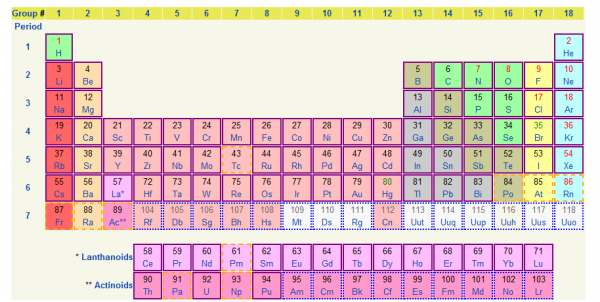

He not only arranged the elements by the degree of atomic heaviness, but also found that the elements had other patterns that repeated periodically. Hence Mendeleev called his table a periodic table, because the patterns repeated with specific periodicity. Through the repetition of this pattern, Mendeleev also predicted the existence of elements not yet discovered.

I listened to this story of Mendeleev organizing the elements on Radiolab, with hosts Jad Abumrad and Robert Krulwich. They ended the story with the following question: Was this organization an invention that Mendeleev imposed on this otherwise random set of elements? Or did Mendeleev see the underlying law that naturally organized the elements? In other words, is organization a human fabrication we impose on content, or do we observe an organization that is naturally inherent in the content?

By the way, I excerpted a short, one-minute clip from the Radiolab podcast here. Listen to the way Oliver Sacks, Abumrad, and Krulwich tell the story of Mendeleev:

Mendeleev apparently rode these trains for years before finally reaching his organizing vision. Here Abumrad and Krulwich elaborate on the principle that Mendeleev rationalized:

And the final result today:

The Problem with Scientific Classification

After listening to the story of Mendeleev organizing the elements, I was convinced I too could find, if I just looked carefully enough, an underling pattern that would serve as the perfect organization for my 200 help topics with Project Swordfish.

But the more I looked, and the harder I thought, I could not come to any conclusion except that a software application is man-made. It does not conform to any unseen natural laws in universe, and finding a natural pattern is an unachievable illusion.

The only system of organization that approximates a natural law is to organize help according to the psychology of the user. In other words, rather than looking at an underling organizational structure in the content, look at the way the user's mind organizes and structures the content instead, and use that mental principle as the pattern.

Having thought through all of that, somewhat fruitlessly, I scrapped the other content organizations and created a standard topic-based TOC that looked somewhat like the following:

Exchanges

Organizing Exchange Locations

Evaluating Suitable Environments

Reading Informant Microgestures

Burn Notices

About Burn Notices

Managing Your Life After the Burn Notice

Dealing with Fake Burn Notices for Double Agents

Sting Operations

Finding and Using Citizen Operatives

Recycling Burned Agents for New Operations

Evaluating Environments in High Risk Situations

Deciphering Informant Trust

Calculating Risks Based on Informant Credibility and Environment Security

This approach to the TOC follows the conventional topic-based approach, attempting to group like-minded content into its logical topic container.

Limits of Logic

This standard seems like a good approach, except that topics don't always fit neatly into their "logical" containers. You can see that in the last section, Sting Operations, the tasks include evaluation of informants and assessment of environments -- similar to topics under Exchanges. The remaining help topics also contained similar overlap.

The lack of a clean, neat grouping of content into topic containers is not just an exception, like the egg-laying platypus is an exception to its mammalian classification. Content in real projects is messy. It overlaps. It duplicates. It stretches outside of its row like an overgrown tangle of weeds. It could easily be classified in several different containers. When you look at the logic of the organization, it often tells you more about the organizer than the actual content. In the end, it isn't really logical at all.

According to Abe Crystal in the Tech Comm Journal, "the idea of a single, unified hierarchy," in other words, the standard topic-based containers organized in a hierarchical, logical arrangement, is "the fundamental weakness of standard IA [information architecture] frameworks."

Yes, this single, unified hierarchy, the traditional topic-based approach to classifying content, which I struggled to grasp and implement with my 200 topics, is an old, tired framework. Instead, Crystal suggests moving in a more fruitful direction: faceted classification.

----------------

Crystal, Abe. "Facets Are Fundamental: Rethinking Information Architecture Frameworks." Technical Communication Journal, Vol 54, No 1, Feb 2007