Organizing Content for Constructivist Learning [Organizing Content #28]

In my last post, I argued that rhetoric is the foundation of communication. Rhetoric is the practice of fitting the message to the context to get the results you want. In the most common scenario for technical writers and instructional designers, the rhetorical context is a learning situation. You want the user to learn new software or hardware.

What's the best way to organize content for learning? In comments on a previous post, Eddie Van Arsdall, an experienced technical writer and trainer on the east coast, commented,

I consider classroom teaching to be the best experience for understanding how people learn. I recommend that technical communicators aspiring to focus on training development and elearning spend some time teaching, tutoring, and mentoring. You're a born teacher, Tom, as is evident by your posts.

I taught writing for about four years -- two years as a graduate instructor at Columbia University in New York and two years as a full-time instructor at the American University in Cairo.

I did better at Columbia than in Cairo. As a graduate instructor at Columbia, we were trained to teach in a specific way. Rather than lecturing to students about writing principles, we asked them constant questions. About all we did was ask questions. When a student responded, we tried to get other students to respond to the student's response, directing the conversation from student to student rather than from teacher to student.

If no one answered a question right away, we waited (sometimes a minute or more) until someone offered a response. The idea was that asking questions in a Socratic method could increase critical thinking and reasoning more than explaining and lecturing. We also gave them weekly essay assignments that required them to reason out answers and determine the best way to organize their thoughts and arguments.

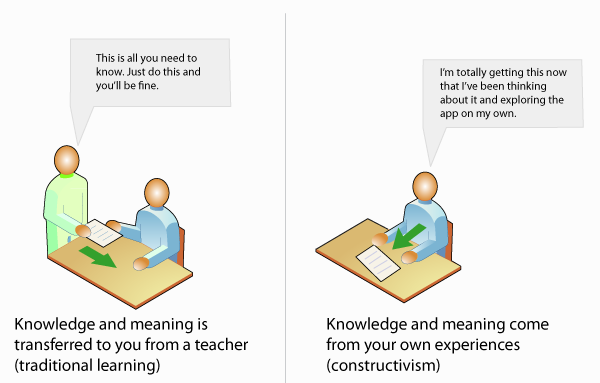

I didn't know it at the time, but this method of teaching derives from a constructivist learning theory. In constructivist learning, you don't transfer knowledge from teacher to student in a hierarchical way. Instead, students construct their own learning through their own experiences. Students don't learn merely from reading a textbook or listening to a lecture, but by acting and experiencing, by teaching and assessing, by exploring the topic on their own. Their experiences and what they make of those experiences is how they learn.

Teachnology, a site dedicated to teaching and technology, provides a good explanation of constructivist learning theory:

The constructivist learning theory argues that people produce knowledge and form meaning based upon their experiences. ... Instead of giving a lecture the teachers in this theory function as facilitators whose role is to aid the student when it comes to their own understanding. This takes away focus from the teacher and lecture and puts it upon the student and their learning. The resources and lesson plans that must be initiated for this learning theory take a very different approach toward traditional learning as well. Instead of telling, the teacher must begin asking. Instead of answering questions that only align with their curriculum, the facilitator in this case must make it so that the student comes to the conclusions on their own instead of being told.

... Instead of having the students relying on someone else's information and accepting it as truth, the constructivist learning theory supports that students should be exposed to data, primary sources, and the ability to interact with other students so that they can learn from the incorporation of their experiences. (constructivist learning Theory)

In other words, the teacher is the facilitator to a learning environment, but the teacher doesn't transfer the knowledge. The student constructs the knowledge through his or her own through experiences, associations, connections, perspectives, and other insights that he or she formulates while in the learning environment.

The Example of Conferences

This learning theory rings true for the way I learn. Every conference I attend is an example of it. I'm always excited to go to conferences, to interact with other professionals in my field, to read the program and see all the topics and issues for discussion. But then I go to the presentations -- all day. And then the next day. At some point, usually early on, I start to tire of going to presentations. Am I really learning something, I start to wonder? Something that I couldn't just get from a book that I read on my own?

That's how all conferences go for me. The problem is in the assumption that learning takes places through lectures and presentations. Superficial learning may take place like this, sitting and listening and taking notes to incorporate what the presenter says. But the real learning, the aha! moments and genuine epiphanies that make the conference worth it, aren't anything a presenter might say. For me, it's an insight that bubbles up on its own, through various experiences and reflections while I'm immersed in the conference learning environment. The conference provides the catalyst for the learning, but it doesn't provide the learning itself.

This is partly why I like to interview people at conferences -- because sessions don't engage me. The lecture isn't how I learn. I prefer to be more interactive. I want to drive the conversation. I learn by doing, acting, and experimenting. The knowledge that surfaces from these experiences is the value I get from conferences.

From Classroom to Software

The way users learn software takes place in much the same way. If you ask people how they learn an application, most will tell you they learn by doing. Patricia Blount asked this question on her blog a while back in her post When you need help, where do you go first? The responses were typical of how most people learn software:

Sometimes you do have to just wing it, though. That's how you learn, by doing.

... When I need to learn a new product I'll consult the user guide only as long as it takes to get the thing up and running. Then I prefer to wing it. I'll consult the help when I get stuck...

... I use a guide to get me started with a product and to get me out of a jam if I can't figure something out. I used to read guides because I wanted to learn everything about the product, but now I'm too impatient to learn.

That last comment is particularly telling -- he doesn't read the manual because he is "too impatient to learn." As much as we may like the safety and comfort of having a manual, the manual isn't how we learn a software application. We learn by playing around in the application, trying to do tasks, navigating the interface, and generally seeing for ourselves how it works. We learn by doing.

When we get stuck, we turn to the help material for the non-intuitive answers, but then we go right back into the application, because that's where learning takes place. Users don't learn by reading a manual and then opening an application to use it. Invariably, users prop up the manual next to their computer and use it as a guide as they explore the application.

In short, users learn by doing, and the only place to truly do is in the application.

Maximizing for constructivist learning

How do you organize your help content to accommodate learning from a constructivist approach? Here are five tips.

Move help into the interface. Put as much help as possible in the interface. If we assume users will be exploring the interface to learn the application, include tips and other help information directly within their learning environment. Little help icons and hover over popups work well for including help without cluttering the interface.

Give assignments to the user. I'm not sure why assignments are so infrequently given in manuals. Perhaps we assume manuals are for reference only and any assignment type questions would be included in a training module instead? But let's assume you have a short introductory guide to an application. Get the user doing as many tasks as possible in the actual application. Give assignments, challenges, and other tasks that get the user applying concepts and principles that you're explaining.

Don't give the user a long manual. Provide an introductory getting started guide, and then put the rest of the information in a comprehensive online help or wiki. I have a colleague who recently single sourced his online help into a printed manual that was about 350 pages long. Can you imagine giving that manual to the user? Users are almost never going to read through hundreds of pages of help material to learn an application. Give them enough information (maybe 20 to 50 pages, including illustrations and screenshots) to get started in the application, and then get out of the way of their learning. Get them into the application as fast as possible. When users have unanswerable questions, they can search a comprehensive online site for answers. But avoid giving them a long PDF with the expectation that they keep their noses in the help instead of the application.

Ask open-ended questions. In the help material, rather than lay out the material so that all questions are answered, why not include more open-ended questions at the end of each section? For example, if you were describing how to enable Internet connectivity in a building, you might ask the reader the following:

- Where do you think the best location to install the ISP's modem would be in your building?

- What's the peak usage you envision for bandwidth consumption?

- Imagine your most stressful event. What could possibly go wrong with the Internet connection?

You could include these questions at the end of a chapter. These questions encourage the user to start thinking about the topic for him- or herself in a more engaged way. This independent analysis and questioning will help the user learn and incorporate the material more fully than if he or she had merely read the answers in a textbook.

Provide a sandbox version of the application to explore. A sandbox version of an application is a clone of the real application, but often with dummy data. With one of my projects at work, we have a sandbox version of an application that we set up new users with all the time. It's a great place to experiment and explore without the worry of corrupting real data or making mistakes.

Conclusion

Many technical writers are often too focused on information. We assume that users can read the manual, or sections of a guide, to learn the software. But this isn't how most learning takes place. Learning takes places through doing -- sometimes acting autonomously and without handholding in an application. Our help should reflect that learning behavior. If it doesn't, we're merely writing reference material that would fit into an encyclopedia.