Looking at the theoretical foundations for tech comm -- Conversation with Lisa Melonçon

Article for discussion

Getting an Invitation to the English Table—and Whether or Not to Accept It. Rentz, Kathy, Debs, Mary Beth, and Meloncon, Lisa. Technical Communication Quarterly, 19(3), 281-299. 2010.

Our conversation

TJ: Lisa, you have one of the most active, visible presences online, especially among tech comm academics. Also, we’ve chatted in podcasts previously and had some good discussions and also met at a previous STC conference. Thanks for agreeing to this conversation.

The article I’d like to explore is “Getting an Invitation to the English Table—and Whether or Not to Accept It,” which you co-authored with Kathryn Rentz and Mary Beth Debs while you were at the University of Cincinnati. I know you’re now at the University of South Florida now.

Just curious, you were at the University of Cincinnati for more than a decade. Why did you move to Florida?

LM: Well, there’s a multi-part answer to that question. First and foremost, I needed to move geographically to see if an ongoing health issue would improve. Since Tampa is similar ecologically to where I grew up, I thought it may help. Second, it was time for a change. It had been. Sometimes within any organization you realize that the structures and goals and such are pretty well set and there won’t be many deviations from that. When you realize that those structures and your goals don’t match, it’s time to move. Third, when you hit a certain place in an academic career, your options are sort of limited, particularly to ensure that the new place can support your research and teaching. South Florida helped in all three areas.

TJ: Your “Invitation to the English Table” article appeals to me for a number of reasons. Primarily, it seems to get to the heart of so many relevant issues, especially for practitioners (even though the focus is presumably on tech comm programs within the academia). In trying to argue whether Technical and Professional Communication fits into the English department, you establish the theoretical underpinnings of tech comm as a practice based on rhetoric, as writing designed as a social act, and other foundational concepts. In arguing for where the program belongs in your university, you’re making an argument about where tech comm belongs as a knowledge discipline — in other words, our theoretical roots and foundation. You explain what it means to be part of the humanities. Those are some of the questions I want to dig into soon.

The effort for the seat at the English table also mirrors, in uncanny ways, tech comm’s organizational uncertainty in the workplace. Just as you’re trying to get tech comm a seat at the English table, practitioners spin their wheels trying to get a similar seat at their company’s table, organized in the right division with representation in higher-level initiatives. I think the strategies you present would also work in the practitioner workspace.

Let’s start with the question you pose in the introduction:

“What does it take—intellectually, ideologically, and politically—for professional writing to become a bona fide member of an English department? And can professional writing accomplish this without compromising its obligation to prepare students to meet the complex challenges they will face as writers and participants in Organizations?”

Can you explain more of the dilemma you present at the outset here? How would this seat at the English table compromise your ability to prepare students for organizations? I’m assuming that you’re describing the problems with teaching technology — doing so would make students too vocational, reducing tech comm to a “skills course” and would undermine the integration into the more theoretical foundation with humanities, right?

LM: At the risk of over simplifying things, I say this: English departments have historically been the home of literature scholars who were and are concerned with having students understand social, political, cultural, and economic views through the lens of literature. In doing so, reading and critique of those readings was a primary goal. The only writing students did was to critique or engage with literary texts.

The rise of technical writing (what is now more commonly referred to as technical and professional communication) in the 1950s and larger boon in the 1980s meant that there was writing that was aimed at the world of work. Which many in the humanities and in english departments see as counter to their own goals. In other words, there is a tension between how to align a liberal arts education with a degree program that focuses on advancing the aims of capitalistic organizations.

Yes, we wanted to make sure that we were making it clear that our program at UC, as with the majority of programs in the US, was balancing the ideals of humanism with the need to teach sophisticated problem solving skills and technologies. In other words, technical and professional writing had to figure out a way to align the goals of preparing students to do things, without it just being skills, and ensuring they were grounded in the social and ethical concerns of a good humanist.

TJ: In the article, you explain the need to integrate tech comm into the English department’s mission and objectives. Then you dive into the theoretical foundation upon which tech comm builds:

In designing our curriculum, we made choices that enabled our program to cohabitate successfully with the more traditional areas of study in the department. First, we used as a center Burke’s (1950) definition of rhetoric: “the use of language as a symbolic means of inducing cooperation in beings that by nature respond to symbols” (p. 43). We also embraced Miller’s (1979) article, “Humanistic Rationale” and Bazerman’s (1983) “Scientific Writing as Social Act.” So from the beginning, we subscribed to a social, interpretive, nonpositivist view of language that enabled us to raise many of the same issues that were being discussed in literature classes, such as how symbols come to have meaning, how form creates expectations, and how social forces shape perspectives and tastes. Second, we drew upon a number of relevant “conceptual areas” in professional writing: “human factors, information design, linguistics, visual theory, management theory,” and many others (Sullivan & Porter, 1993, p. 408). Finally, we also found inspiration in Schön’s (1984) popular book, The Reflective Practitioner, which supported our view of professional writing as a field that combined techniques, skills, and pragmatics with theory, reflection, and critique.

I’m fascinated by the references here, and I need to do more reading. Why did you connect tech comm to Burke and rhetoric? Are technical writers “inducing cooperation” with their users? How so?

LM: Can we take one step back before I answer this question? It’s an important step to understand something not only about this article, but the purpose of academic research. I was surprised that you chose this article because in some ways it’s totally an academic argument. It was made for other faculty and administrators in technical and professional communication programs housed in English departments, but more so, it was made specifically for our colleagues in our department. Another audience would be folks in other English departments. This is an important point about why we connected Burke in that paragraph. It was a move to pick a theorist that may be known outside of writing and rhetoric that would lend credibility to our argument and therefore the field.

This was written at a time that we had just managed (after previous failures before I was hired) to create an undergraduate track in professional writing. This article was a move to continue to show our value but also to demonstrate that we understood the politics and dynamics of a departments with multiple parts that don’t always see things the same way. I didn’t agree with parts of it when we wrote it, and this was the most contentious thing I ever collaborated on. It’s not that Mary Beth and Kathy and I didn’t get along. We did, but we see the role of technical and professional writing differently.

But even though I didn’t totally agree with the use of Burke, it made sense to ensure that we were grounding our arguments within the literature of the field. And many in technical and professional communication use rhetoric as one of its grounding theories.

So yes, we were trying to “induce cooperation” with our colleagues in much the same way that a technical communicator will write and design documentation in a way that a user may engage with it. The way those arguments may be framed — or the way rhetoric invoked — would be entirely different, as would make sense with diverse audiences.

The “how so” part of your question is basic tech comm 101: know your audience and try to craft a document that they’ll read and understand. As you know, easier said than done.

TJ: If there’s one word that tends to separate academic discourse from practitioner discourse, it’s the term “rhetoric.” As I understand it, whereas Aristotle’s rhetoric connoted more manipulation to achieve certain ends of the rhetor, Burke’s sense of rhetoric is a way of achieving more cooperative ends through methods of communication — choosing the right language and approach for your particular goals. I know this is a huge topic, but can you give us a clearer sense of what academics mean by rhetoric as it applies specifically to technical communication?

LM: Oh, Tom [she laughs and laughs and laughs]. I laughed at this question because for years I have said I was not a rhetorician. It wasn’t until I became the editor of journal (related to but not in tech comm) that uses rhetoric in the title that I had to fully make peace with rhetoric. Rhetoric is one of many theories used to help us understand language. The other reason we used Burke in this piece was because Mary Beth is a Burkian, meaning she has used his work a lot as an orientation. But we could have used all sorts of rhetoricians or rhetorical stances to say the same thing. Rhetoric is also useful because it was used to teach people how to persuade and to get things done, which also helps align it with the field’s teaching mission.

Rhetoric is huge thing that has been ported, expanded, theorized, debated, and a thousand other things. But, most fundamentally, for most folks in technical and professional communication, they use it as a way to underscore the need to focus on purpose and audience. In the last 15 years or so, there’s a move to take rhetoric and merge it with something else so that you have the attention to language and purpose and audience, but also the attention to things like culture or stance or gender.

I will say this, too, from a practical standpoint: If technical and professional communication had somehow come out of other origins or departments, we’d probably have a different set of theories that are prominent. Our location in English departments and how we train our PhD students (those people who teach and run our programs) are unfortunately latched to rhetoric as a higher education differentiator. And it also depends on the program you come out of. While I took a number of rhetoric courses, my theoretical orientations were in other areas so I don’t rely on it as much as some.

TJ: Burke’s Pentad refers to his dramatist approach to analyze a work by looking at five elements: agent, act, agency, purpose, and scene (and attitude). The agent negotiates his or her communication approach and strategies based on these elements. I remember a couple of years ago, you and I had a podcast with Jacob Moses about the three types of knowledge tech writers need to succeed, where we talked about the need to understand product knowledge, technical knowledge, and user knowledge as shaping elements that define the tech writer’s approach in docs. (I also wrote about this triad of topics here.) And Bob Watson’s presentation at 2018 WTD, “Audience, Market, Product: Tips for strategic API documentation planning”, situates the writer’s strategy with API docs around concerns and awareness of audience, market, and product. When we root tech comm in rhetorical foundations, are we saying that tech writers negotiate communication strategies by analyzing these contextual elements?

LM: Absolutely. That’s exactly what it means. Rhetoric is context; it’s an awareness of it. Do we need rhetoric’s terminology to fully understand that as practitioners? No. Can I teach technical communication without rhetoric? Yes. But, I find that I use it in its most basic ways to help students understand that I’m not just making stuff up. Bob is basing his practically applied tips on concepts and ideas that have been tried out for millennia. That’s a pretty strong case for doing things a certain way, no?!?!

TJ: You also referenced Charles Bazerman’s “Scientific Writing as Social Act.” As I understand it, Bazerman was looking at writing across the disciplines and noticed different genre conventions and techniques in the way they approach and disseminate knowledge. He developed the notion of a “rhetoric of science.” It seems that there is a “rhetoric of …” about nearly anything these days. Burke’s books were called A Rhetoric of Grammar, A Rhetoric of Motives, etc. I’m exposing my ignorance here, but what do we mean by “a rhetoric of …” in this context? Is this like a set of guidelines for effective communication within a discipline?

LM: [laughing, laughing] yes, there is a rhetoric of all sorts of these things days. When folks in other disciplines, like literature, use something like “the rhetoric of wonder” they are actually just using rhetoric in place of language. But for Bazerman, his rhetoric of science was following some work coming out of sociology that science wasn’t as objective as everyone thought and that science was also socially constructed (Latour and Woolgar Laboratory Life). Bazerman wanted to show that the language used to create science was rhetorical, that is was persuasive and had distinct features. For Burke — and I would never call myself a Burke scholar — he was simply saying that grammar and its functions were also persuasive acts.

In other words, where we situate and use grammatical structures impacts the way writing and communication is received. For Burke, that’s rhetoric.

Honestly some days I buy this idea and other days not so much. I definitely don’t fall into the camp that “everything is rhetoric.”

TJ: In your article, you mentioned that you were able to position tech comm within the English department because of the shift within the English discipline towards more social and civil acts. You said,

Our emphasis on the social, interpretive dimensions of communication dovetailed well with the direction in which professional writing, composition, and English studies as fields were all heading.

Later you expand on this a bit more:

Over the past 20 years, the literature side of English has moved away from aesthetics toward cultural and discourse studies, which has broadened both the kinds of texts that literature faculty count as worthy of study and their appreciation of the real-world “work” that texts do.

Can you expand on this direction? I agree that technical and professional communication is designed to induce action in the reader. One does not read documentation for delight in language but rather reads “to do,” as some have phrased it.

LM: Just like the practice of technical communication has changed over the last 20 years so has the way people in higher education research and think of things. Often times, academia goes through “turns.” What this means is that all of sudden you have a scholar or a group of scholars who introduce a new theorist or a new set of theories into a field or discipline. Then the next thing you know that starts to seep across all disciplines, especially related ones like the humanities and social sciences. For example, there was an “affective turn” about 10 years ago when scholars were interested in how emotion and the broader term of affect could influence X or Y or how could affect help us understand Z phenomenon.

Literary studies and creative writing became more aware of cultural studies and discourse studies during their own disciplinary turns. Those two areas are things that technical and professional communication scholars have been concerned with, so all of a sudden there was a sharing, or at least a better understanding, of approaches and theories. This embracing of different trajectories also helped our colleagues at UC understand that we were actual scholars and not just teaching students where to put the common in a business plan that would ruin society.

TJ: I can see how rhetorical approaches might seem more interesting when there’s more at stake. For example, I’ve been writing a lengthy competitive analysis whose true agenda is to expand our team’s visibility by showcasing our insight into the the larger user journey. With some docs, however, the rhetorical situations aren’t very interesting. I mean, the user is already ready to cooperate. The user stands willing and fully open to completing the task I describe (if I can only articulate the steps clearly). There’s no sense of me inducing cooperation from a semi-unwilling participant. If the other doesn’t need any special inducement to cooperate, is rhetoric still interesting to analyze in these situations? Is this maybe why more academics don’t focus specifically on documentation scenarios when it comes to rhetoric?

LM: This is where you and I totally agree, cause I’ve been where you have been and still do consulting work. But this also where many of my colleagues in technical and professional communication wouldn’t agree with either one of us. And that’s due in large part to the fact many of them have never done sustained work outside of higher education. I use sustained here deliberately because many academics will hold up a single consulting gig or a short term job of some type or part of a research project as workplace experience, which you can tell from my adding this that I don’t buy. But, I want to be clear. I’m not discounting their knowledge or what they did. I am simply not in agreement with their argument that they can draw big conclusions about the field or teaching or research from such experience.

TJ: Exactly how I lead the user along a series of tasks to achieve a “cooperative” end might rely on various techniques — journey maps, clear definitions of terms, instructive visuals, and more. But that context isn’t as interesting as perhaps a marketer deciding how to position a product, or even a blog post where I make an argument of some kind. Does rhetoric really describe what tech writers are doing in documentation? Or is the use of the term “rhetoric” actually our discipline’s rhetoric (in a meta way) for finding common ground with the English discipline?

LM: Rhetoric as you use it here is both, I think. But much of the user experience you describe may not be called rhetoric by some. I wouldn’t call it that. Much of those ideas are drawn from psychological research into how we read and process information. Sure, rhetoric, particularly as a teaching tool, talks about choosing the right word and ensuring correct definitions, but that’s also just common sense, too, right? Once you’ve worked in tech comm long enough there are things you know, particularly specific to your industry of niche.

In other words, when you invoke a theory and when you invoke a research is contingent on what you’re trying to accomplish. I guess that for some, describing the contextual nature of a problem is also rhetorical. This is something that needs to be understood if more academic research is going to be valuable to practitioners. It’s in parsing through the academic jargon to get at what could be an important takeaway. And most importantly, knowing or figuring out what research is best suited to being applied by practitioners.

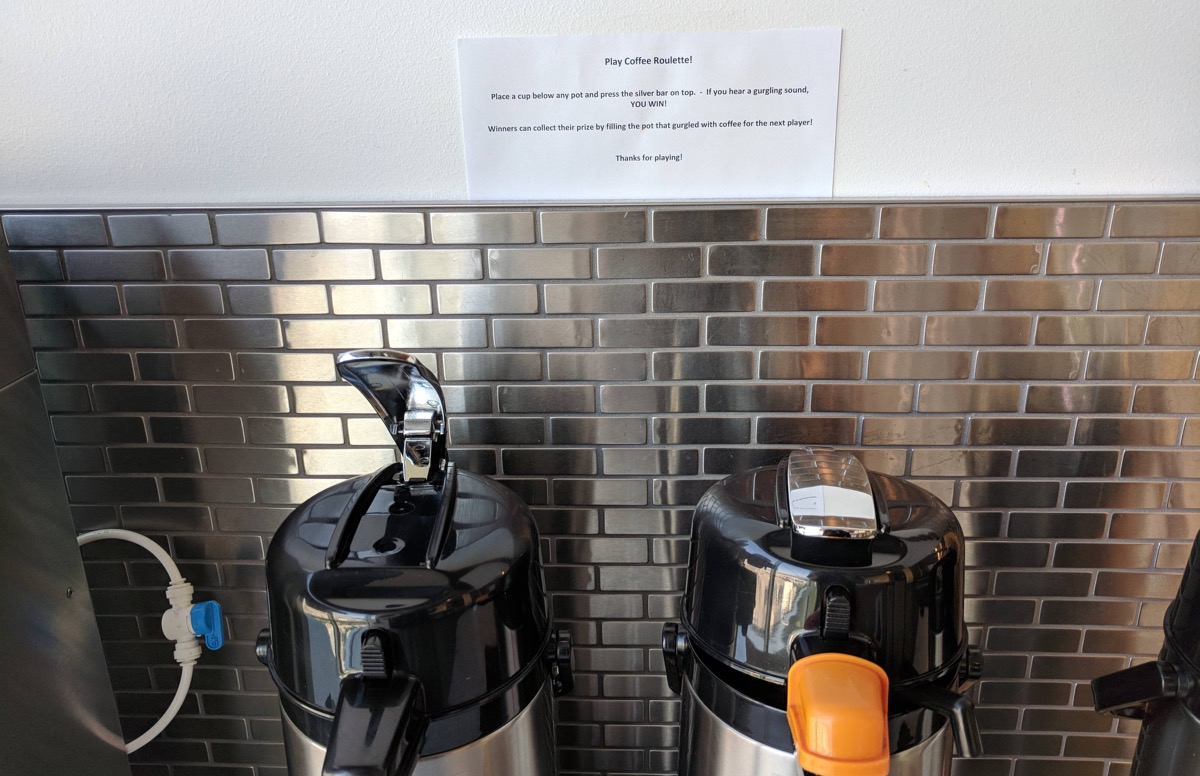

TJ: We have a sign in our break room that tries to get users to make coffee when the pot runs out:

The sign reads,

“Play Coffee Roulette! Place a cup below any pot and press the silver bar on top. - If you hear a gurgling sound, YOU WIN! Winners can collect their prize by filling the pot that gurgled with coffee for the next player! Thanks for playing!”

Is this rhetoric? Could I say there’s a rhetoric for breakroom coffee making? If so, it seems that most anything could be classified as rhetoric. I mean, we often communicate to influence some uncertain result all the time, right? I might email my boss to say that I’m working from home due to an appointment at the auto shop. Am I a rhetor engaged in a rhetorical scenario to induce cooperation from my boss to grant my work from home request? Are we dressing up the obvious in fancy language?

LM: I could find you a colleague or two (or a hundred) who would probably claim that sign in the break room is rhetoric. I am not one of them. As an anti-academic, that is someone who is painfully practical; that sign is simply a clever way to sort of shame folks into doing the tedious task of keeping the coffee pot full.

Some would go as far as to argue that parts of rhetoric are so culturally ingrained that they are simply part of our day-to-day life. This is the tricky part of teaching and working and researching in an area where everyone does it. Everyone writes. But as you know, not everyone can be a good technical communicator without training either through a degree or self education or courses or they are trained on the job.

TJ: Reading your article made me feel like I’d sort of missed the foundation I need in order to take my strategic thinking to the next level. I am not very aware of the theoretical contributions from some of these authors that should be shaping my approach, and I should be. You wrote,

Much of the theory informing English studies today—the ideas of Foucault, Bakhtin, Bourdieu, Baudrillard, and others—can help form an invaluable conceptual framework for budding professional writers. For its part, professional writing has shifted away from a focus on “fidelity” and information transfer to a more sophisticated view of language—one that is more interpretive, more discourse based. This movement by literary studies and professional writing enables a department to emphasize common intellectual ground.

I like the idea that I’m negotiating strategies within a more sophisticated view of language, interpreting and engaging in specifically calculated discourse. But truth be told, I’m usually just trying to understand my user’s needs and communicate the information in plain language. Am I doing some of this more sophisticated thinking unconsciously? Or am I not stepping outside of the writing mode and analyzing these elements in a more strategic, analytical way (like a content strategist might as opposed to a mere writer)? How can I take my tech writing to the next level so that I’m immersed in more interpretive discourse to pull the user down a path he or she may not initially want (or be able) to go?

LM: Yes, you are doing this thinking unconsciously and you’ve pushed your own thinking by constantly reading and engaging.

You know, I was never a theory person. I didn’t totally get it. I read a lot of stuff, but I just had trouble getting past my own practical nature. Then I realized that there are theories and Theories. Big ‘T” theories are the great thinkers that encourage you to contemplate big questions and ideas, but little “t” theories are simply a system of ideas intended to explain something (from dictionary.com) Thinking of theory is this way actually makes it more practical. A theory just helps you see something differently.

So, I do a lot of work in health communication, and as I explained [here](http://tek-ritr.com/pubs/patient-experience-design-pxd/](http://tek-ritr.com/pubs/patient-experience-design-pxd/), I was frustrated with the current approaches, practies, and theories. I knew some of our present ideas weren’t working because we were encountering failure after failure in this project. As an example that influenced part of this project, I happened to read a book by Theresa MacPhail, who is a medical anthropologist, and her take on what “context” means (and she never once mentioned rhetoric) helped me to see things differently. Thus, I formulated my own theory that I am now testing to see if it works.

I give you this anecdote to encourage you and to reassure you that you’re doing everything right to continue to push your own boundaries. You’re talking, you’re reading, you’re engaging, and you’re thinking and questioning.

So, you may want to try some theories. Not secondary, that is, you don’t want to read what anyone says about a theorist. You want to read the theorists themselves. Then you do what you do and just think through or talk through how it could be applied to our own situation. In your case, you may want to read some work in organizational communication which deals with a lot team building or how collaboration works to give you insights into how to potentially move your team. Theorists in psychology are always useful in user experience. Otherwise, I say that just consistently engaging with people who have different experiences and perspectives is a great way to challenge yourself on a big level. On the smaller level, ask to have different duties. Like you say, you enjoyed this report project you just did — a shift in writing every once in awhile is definitely a good way to sharpen your skills across the board.

TJ: As you describe strategies that worked for getting a seat at the table, you said constant participation and alignment with the English department’s mission was key:

Sullivan, Martin, and Anderson (2003) argued that it is only through “the individual practitioner’s effective participation in local endeavors that preconceived notions of his or her status will be restructured” (p. 116). Although they were specifically referring to technical communicators in the workplace, their contention applies equally well to professional and technical writing faculty members and their place(s) in academic departments.

The more professional writing faculty are able to “effectively participate in” and contribute to the department’s goals and objectives, the more likely the department as a whole will begin to “restructure” its notions about the place and worth of professional writing. In effect, professional writing faculty must model the same rhetorical skill that we hope our students will develop.

As our field’s absence in the English studies literature indicates, professional writing faculty need to work hard to make their presence known and valued in an English department — or perhaps any department not exclusively their own. What this has meant in our case is that we have had to be constantly representing ourselves, constantly present on important department committees, persistently generous with our service to the department.

Let’s take this same argument to the workplace. (In fact, you noted that one of the authors you quoted was specifically talking about the workplace.) Suppose I feel our tech docs group is at the bottom of the totem pole, constantly struggling to get funding, visibility, recognition, and other traction. In short, we don’t have a seat the organizational table. You’re saying that we should participate as much as possible in the larger objective of the group we want to be part of (e.g., Engineering)?

LM: Yes, sir. You have to participate and do things you may not want to do to start to shift or change cultures where you get a better seat or a different seat.

It’s hard and it doesn’t always work. Within a couple of years there were some drastic shifts in the department where some of our argument no longer held, and the shifts involved structures that were never going to change — this is what helped me make the final decision to leave.

Any organizational change is hard. It’s painful because it always seems like someone or a division is going to have to give something up to give you what you want. That’s only partially true. Most of the time, changes aren’t meaning someone is losing something. It’s just a shift in mindset. Engineering needs to know that your division is better suited to be aligned with them. It becomes your job to figure out where those overlaps are, what language they may understand, so they can see how valuable you could be to them. This one of the things I did as a consultant. I know it can be done, but it takes time and patience.

TJ: In the past, I’ve been conflicted about attending agile scrum meetings across multiple projects because they seem like a time drain. One sits in a meeting where 90% of the discussion doesn’t relate to docs. But if I want a seat at the project table, would you say that participation in agile scrum meetings is critical (even if it reduces my efficiency)?

LM:[laughing again] I laugh because I know lots of folks believe in scrum, and I have worked in a lot of places where they use this approach. But I have never seen it work effectively.

I think taking this idea of where you sit or where you want to be should be part of larger conversation about your own personal goals, the goals of the team you’re on, where you may want to be and the organization where you work. It’s a tough call. I would always tell folks to your own mini-ROI. Is your time investment worth the potential return on that investment? You could also frame it as a cost-benefit analysis, which works better for thinking of your team as it relates to other parts of the organization. Parts of any of the continuous improvement models used in workplaces can be streamlined to help you or your team make strategic decisions. In this way, it’s a lot of theory or rhetoric: you just gotta figure out which part really applies and is useful for you at the moment with the decision you need to make.

TJ: You’re very active in practitioner spaces even though it seems most of your research is geared towards academic programs and research techniques. Are you participating in practitioner spaces for much the same reason you participated in these meetings and initiatives to get a seat at the English table? Only in this case, you’re getting academics visibility with practitioners, ensuring they have a seat at the practitioner table (whatever that is)?

LM: I still work as a consultant, and participating in those practitioner spaces also keeps me abreast of what’s happening from a practitioner standpoint. Much like you (as this project shows), I want to learn and to grow. I can read all I want, but since I came to academia after a working career, I can’t see how anything works until I go back to industry and organization and talk and observe and work. I can tell you my participation in practitioner arenas doesn’t really count for much in my academic job. But it counts for a lot to me personally in how I teach and the research that I do and how I work in my community and in different organizations.

TJ: Your article title is “Getting an invitation to the English table—And whether or not to accept it.” But I don’t remember more discussion about the “And whether or not to accept it” part. What are the advantages of not aligning our discipline under the English or Humanities umbrella? Does grouping Tech Comm under English lock ourselves into an association with rhetoric instead of engineering and technology? If we instead grouped Tech Comm within Engineering or Communication, would our theoretical underpinnings, even the foundation on rhetoric, be very different? Or would this reduce us to a vocational skills course?

LM: We never really did talk about the accept part, did we? In higher ed, faculty have very little control over where our programs are placed. Even if you want to move to another location, it’s really hard. That was the key part of this article — to help folks to figure out, through our institutional example, how to make the best of it.

But, yes, I said before, if technical and professional communication programs were in different departments, they would look different There are a few in engineering schools and a good number in communication departments; some programs are housed and administered at the college level, which means a little more flexibility in courses and changing courses when you need to.

In my view, and something that I write about in a book I’m working on about programs, the location doesn’t so much matter as long as faculty are committed to creating and to sustaining curricula that move students toward being “critical pragmatic practitioners,” which is an academic term for simply preparing students to make things and write things with an eye on ethics and to use technologies effectively and ethically, while also learning organizational structures so they can persuasively challenge or ask questions to effect change within organizations and outside of them.

TJ: Can you speculate based on analogy — where should tech comm departments be grouped within a company organization? Is there an equivalent of the English department at a tech company? Would it be Marketing? After all, if there is a group that tries to influence others and induce cooperation, it would be Marketing. But most tech writers consider marketing the dark side, presumably because of their manipulative component and immersion in untruth. Tech writers like to think they write with perfect transparency, providing helpful information in raw, unbiased ways and without agendas. But doesn’t that view sort of shortchange the rhetorical situation that makes the work of tech comm interesting?

LM: This question aligns with an argument I’ve been making for a while now in academic circles — we have to expand what practitioner means. As you know from the shifting of STC and some of its attempts to expand the definition and to draw more members, we have to think of the work of technical communication around the idea of “technical” meaning relating to a particular subject, art, or craft, or its techniques. That’s at the heart of what a technical and professional communicator does even if its in marketing communication or corporate communications (whoever is in charge of the content). No matter if you’re writing truly technical stuff, it all needs to align with broader goals. And when all the folks concerned with content are housed together, you have greater strength to make arguments for change or resources or what have you. In any organization, like items — so to speak — should be grouped together.

About Lisa Melonçon

Lisa Melonçon is an Associate Professor of Technical Communication in the Department of English at University of South Florida. Her primary research areas are the rhetoric of health and medicine and programmatic issues within the field of technical and professional communication (TPC). You can learn more here:

- Website: http://tek-ritr.com/

- Twitter: @lmeloncon