Research on code documentation -- when not to comment on code

Research on code documentation

For the next topic in my Simplifying Complexity series, I plan to tackle the topic of documenting code. Programming code, such as Java, C++, or any other language, remains one of the most elusive and difficult topics to document. In part, this is because most technical writers aren’t already fluent in the programming language. But even for writers or developers who are fluent in the language, code is hard to document. There isn’t a step-by-step process to follow. Code is often arranged in non-linear order, so you can’t simply proceed line-by-line through it. There’s also the question of how much to document, what to cover, and where to include the documentation. Overall, best practices for documenting code are somewhat fuzzy and undefined.

In the next few weeks, I’ll try to tackle this topic in a piece-by-piece fashion, eventually building up the material to form a longer essay. For now, I’ll present and summarize some research that has been done on documenting code.

One of the most exciting articles I’ve found on the topic is “When Not to Comment: Questions and Tradeoffs with API Documentation for C++ Projects,” by Andrew Head, Caitlin Sadowski, Emerson Murphy-Hill, and Andrea Knight. This article was published in the 2018 ACM/IEEE 40th International Conference on Software Engineering. (To read the article, see this ResearchGate link. I also found it online here.)

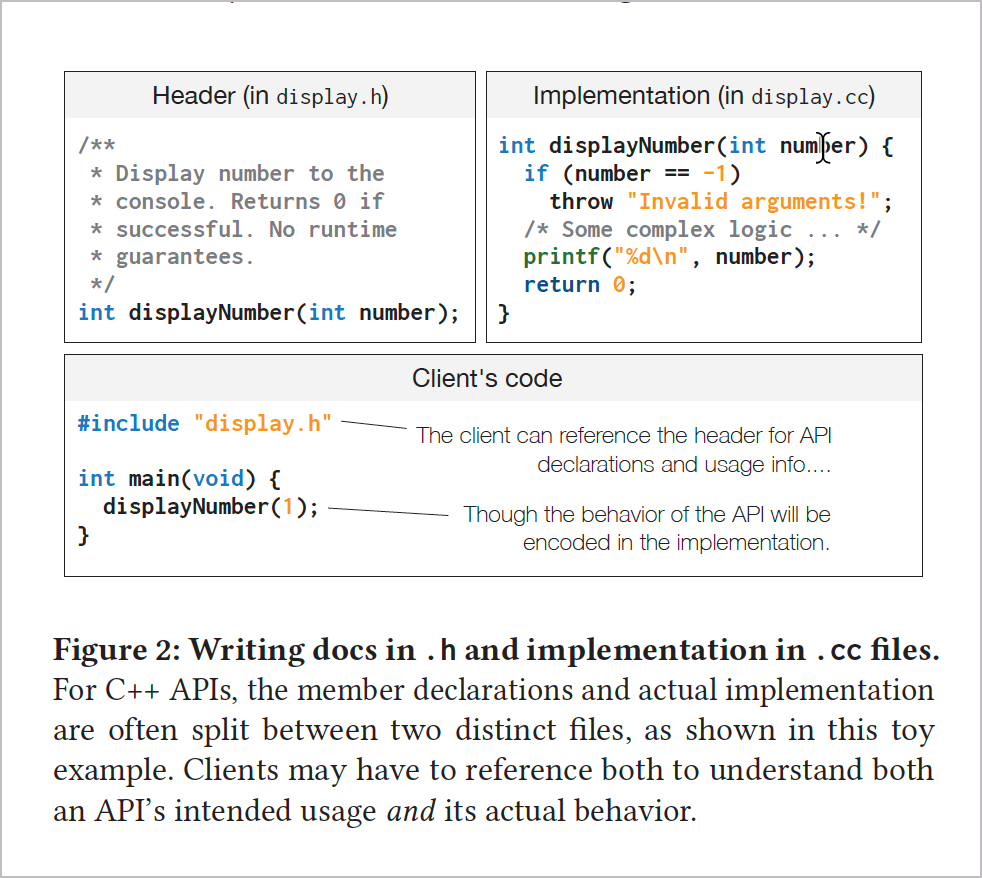

This research combines efforts among academic researchers, engineers, usability specialists, and members from Google’s Engineering Productivity Research team. Given how important documentation is for understanding code, the researchers wanted to know the best location for documentation as well as what information engineers want in docs. Specifically, they focused on C++ APIs and asked whether engineers are more inclined to consult the header files (where classes are defined) or the implementation files (where classes are implemented) for the information they need. The following screenshot (from their article) describes the difference between header and implementation files:

Basically, in C++, the header files (.h) contain the classes and the main documentation. The implementation files (.cc) instantiate and implement the classes from the header. Implementation files have comments peppered in with the code, whereas header files have more formal documentation that follows specific annotation conventions.

The researchers used tracking tools to identify when developers would switch from one file to another, and they also interviewed the developers as a follow-up. Google has about a billion lines of code stored in a central code repository that can be used across the company, so thousands of developers might find and discover code to use in their projects. The team that uses an API might not know the team that developed the API, and vice versa. The researchers gathered information from more than 600 participants in their study.

Where developers look for documentation about code

Overall, the researchers found that most developers looked in the header files for documentation:

Survey respondents reported it would be most convenient to find answers to many of these questions in header files, though interviewees indicated code could be accurate and quick enough to read in many cases.

The researchers also found that, for simpler APIs, many developers read the code (rather than consulting the docs) to see if they can quickly understand the API. Some developers have philosophical views about distrusting the accuracy and currency of documentation and prefer to view the code as the primary source of information. In some cases, maintaining documentation for code becomes more of a liability and a hindrance for developers. For simple code, doc just gets in the way or becomes outdated (thus misleading and harming the documentation’s credibility).

Beyond skipping docs when the code is simple enough to understand on its own, the researchers also recommend avoiding docs while development is in constant flux (because it would make documentation a constantly evolving target). The researchers say you might also consider skipping code documentation when there aren’t sufficient resources to keep the documentation updated. When maintainers can’t keep the documentation up to date, it “rots” and becomes more of a liability.

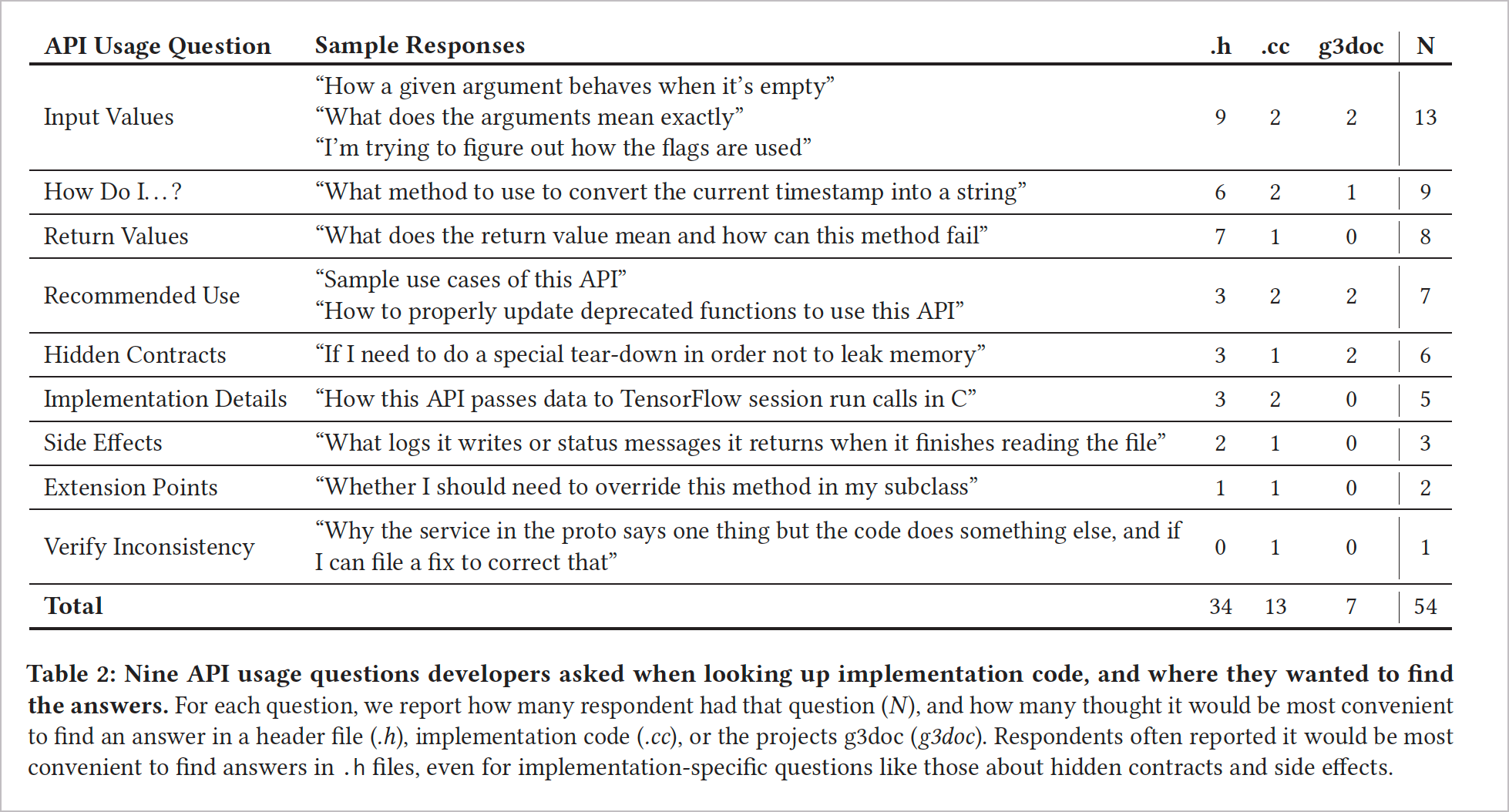

The following chart shows when documentation might not be necessary with code:

However, for more complex code, especially where multiple files and generated code might be involved, developers still relied on documentation to understand it. The researchers explain:

When isn’t code enough to be self-documenting? Sometimes, developers had no problem reading code, and in fact preferred it for finding more accurate information. However, there are some cases where self-documentation isn’t feasible, like code with overly complex method signatures and generated code. Other details, like recommended usage, just can’t be conveyed by source code.

When to document code

The researchers find that there’s an ideal time for writing and updating documentation:

This study also shows the messiness of proposing updates to documentation. The ideal time to propose changes to documentation is during code authoring and review, possibly through a surrogate like a code reviewer. Documentation can get updated only infrequently after it is initially written, as future updates may raise questions of whether the information adds clutter or redundancy.

In other words, write the docs when the code development is still fresh in your mind (or in the developer’s mind). If you wait too long after active development finishes, the documentation will likely be neglected and forgotten, as developers move on to other projects.

What questions to address in code documentation

The researchers also try to understand what types of answers and guidance should be in the documentation. This is a more difficult, broad question, and their answer is generally “API usage.” More specifically,

Most searchers and maintainers we interviewed had opinions about what did belong in documentation, at both the level of headers and in-line comments. Maintainers and searchers mentioned the importance of describing how a file relates to other files in the project (S17), the state of the world when a method is called (S8), executable examples (M5, M8), implementation comments for future maintainers of an API (M5), explicit links to external documentation (M5), semantics of a function (M8), main concepts that someone should understand and know to use the API (M8), “what” the code is doing and “why” at a statement level (M6), and even a proof of correctness (M6). It is unsurprising that not all of this information was available for all of the APIs we saw during this study.

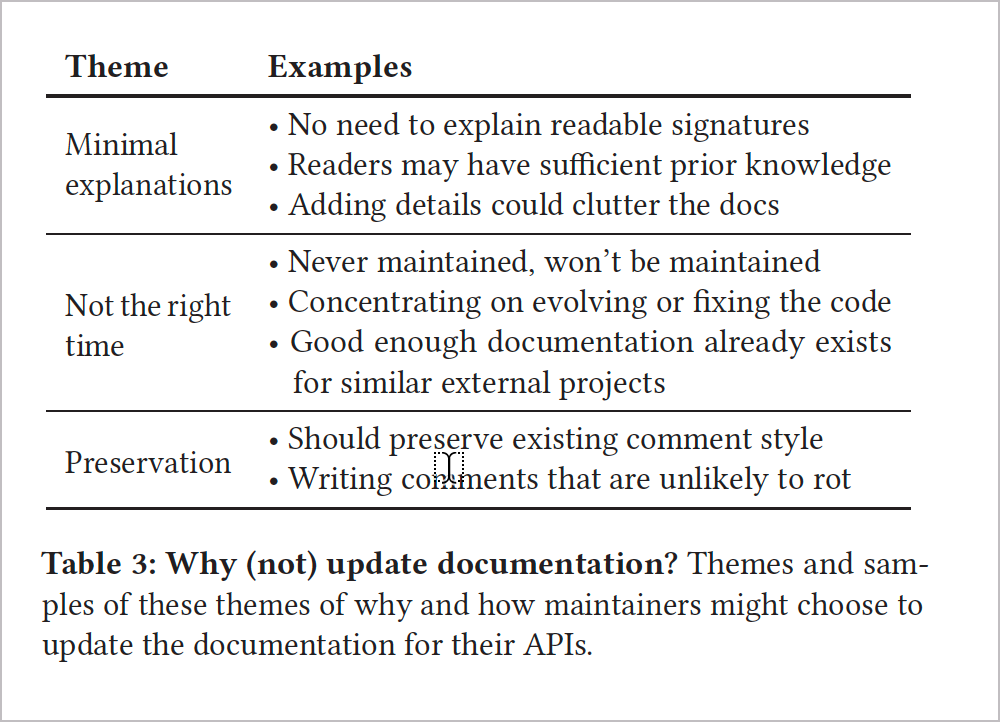

The researchers arrange this information into a chart for readability:

Conclusion

Overall, this research has many insights and conclusions. Probably the main takeaway, as expressed in the title (“When not to comment”), is to recognize when code is simple enough that it doesn’t need documentation. However, making this decision must surely be difficult because it presumes that most developers have the same technical level. More advanced developers can probably extrapolate the API’s usage from code, but beginning developers might need more handholding. Do comments interfere with readability for advanced developers but aid readability for new developers?

Skipping docs based on the assumption that code is more readable on its own also assumes that you can trust the judgment of the engineers who designed and created the code. In my experience, the development team almost always overestimates the level of intuitiveness of the code they wrote and assumes more capability in their audience than the audience actually has. How many times have you heard engineers say, “Users will understand this — and if they don’t, they shouldn’t be using the API.” Are the risks of omitting docs greater than the risk of including them?

The article addresses many of these concerns and presents a complex view about each of these facets — where to store documentation, when to document, what questions to address, and more. There’s not always a clear path to follow (it’s messy), and many environmental, product, and audience details must factor into the documentation strategy. Still, this article provides solid research and probes the topic in illuminating ways.