How to design API documentation for opportunistic (active, experiential) learning styles

Study on how developers use API docs

The latest issue of Communication Design Quarterly, a publication of SIGDOC (the Special Interest Group for Design of Communication), features a highly relevant article called How Developers Use API Documentation: An Observation Study. Several researchers from Merseburg University in Germany — Michael Meng, Stephanie Steinhardt, and Andreas Shubert — set out to “understand how developers use documentation when starting to work with a new API.”

Their methodology is fairly straightforward: they “asked software developers to solve a set of pre-defined tasks using a public API unfamiliar to them on the basis of the documentation published by the API provider.” Basically, these users had to figure out how to construct REST API requests with the right parameters and other configurations in order to send requests that would return the needed information. The researchers then observed how the developers used the API documentation to figure out the tasks.

There are a lot of great observations and conclusions in this article. I’m just summarizing and highlighting the information here. I recommend that you read the article for the full details.

Systematic versus opportunistic behaviors

The authors present some previous research about “systematic” and “opportunistic” learning behaviors. These terms are typically how previous researchers describe the contrasting user behaviors.

You’re undoubtedly familiar with these two types of behaviors. Sometimes when you get a new device, you just start pushing the buttons and exploring how it works based on inputs and responses, trial and error (this is “opportunistic” behavior). Other times you might crack open the user guide and start reading from page one (this is “systematic” behavior). Other times you blend the two modes (“pragmatic” behavior). Same with developers using an API.

The authors describe the opportunistic behavior patterns in their study as follows:

… these developers worked in a more intuitive manner and seemed to deliberately risk errors. They often tried solutions without double-checking in the documentation whether the solutions were correct. For example, P10 changed parameter values to values that seemed to match based on experience with similar problems, but he did not check in the documentation whether the values were actually correct or even existing. P2 inserted parameters that he had noticed at some point in the documentation before, but did not attempt to re-consult the relevant section of the documentation to make sure that the parameters were spelled correctly. …

We found that opportunistic developers in our test started the first task with some example code from the documentation which they then modified and extended. Once a task was completed, the piece of code that solved the task was used as starting point for the next task, which again was a potential source of error. Developers in this group worked in a highly task-driven manner, but also tried things that were not related to the task, but possibly helped them to build a broader understanding of the API in passing. For example, P9 submitted a request for a UPS service (United Parcel Service) which was not required by any of the tasks, simply in order to see what would happen.

We noted that developers which we assigned to the opportunistic group did not take time to get a general overview of the API before starting with the first task. They scrolled briefly through some pages of the documentation, checked the tools available and then started with the first task. Developers from the opportunistic group wanted fast and direct access to information. They did not systematically read larger sections of the documentation, but typically searched for a specific piece of information and then scanned the documentation

In contrast, the systematic developers approached tasks like this:

In our test, we note that these developers took some time to explore the API and to prepare the development environment before starting with the first task. Moreover, they took some time to get a general orientation. For example, P7 and P8 studied some sections in the documentation, then sent a GET request to the API and analyzed the response to check whether the request-response process worked as expected.

Designing for opportunistic behavior

When I’m writing docs and structuring my help system, I admit that I often have the more systematic developer in mind — the one that will read the material from start to end, the one who begins at step one, reads conceptual introductions, and then proceeds to the code examples and such. But it seems like that learning preference doesn’t describe a huge percentage of learners. It’s probably better to design for the opportunistic behavior, since this behavior pattern tends to go against our natural inclinations for linear and top-down information design. The linear/systematic behavior might be more accommodated by default, but the non-linear/opportunistic behavior tends to be more neglected.

How do you design for opportunistic behavior? If you recognize that users learn this way, you’ll put more emphasis in code comments and code samples, more emphasis on error messages and troubleshooting, more emphasis on interactive experiences (such as Swagger UI) so developers can try out requests, more emphasis on clear navigation and search to facilitate the user jumping around for specific information.

The authors call out some of these design patterns in their recommendations. The second half of the article provides recommendations such as:

- “Provide transparent navigation and a powerful search function”

- “Provide clean and working code samples”

- “Enable fast use of the API”

- “Provide important information redundantly”

- “Organize the content according to API functionality”

A note on “opportunistic” terminology

Note that “opportunistic” isn’t the author’s own terminology choice (it’s a term previous researchers used), and I admit that I dislike the adjective (though “systematic” is all right, since it doesn’t cast the learning style in a negative way). No doubt opportunism was chosen to characterize someone who looks for immediate opportunities to act, but opportunism more commonly has a negative connotation of exploiting a situation for personal gain.

The authors say that opportunistic behavior “bears many similarities with the exploratory and active approach described by John Carroll …” Is “exploratory” or “active” or “bottom-up” learning a better description? I feel like I should be able to offer a better word, and I’m guessing that educators have terms for these learning styles. Personally, I like intuitive or experiential or even impulsive learning more than opportunistic. But I’m still on the hunt for the best word here…

Where users spend the most time

Despite the differences in learning preferences, the researchers found that “the strategy a developer follows does not seem to predict a tendency towards using information from the Concepts page in our test.” In other words, just because you’re an opportunistic user, it doesn’t mean you always skip conceptual explanations (it’s just that you might not start there).

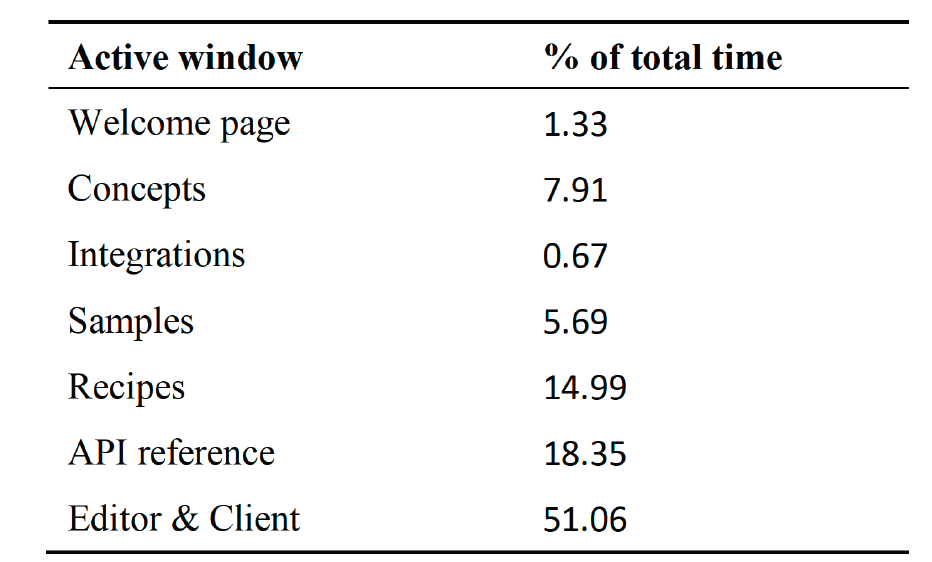

The authors measured the time users spent in various parts of the documentation:

Regarding the different information types, the authors say users looked for topics rather than categories of information — in other words, they didn’t necessarily distinguish between Concepts versus Recipes versus Reference information types as they searched for information. As a result, the researchers recommend a more topic-based organization strategy:

Organize the content according to API functionality. A first aspect concerns the high-level organization of the API documentation. From the results of our study, we conclude that API documentation should be structured according to categories that reflect the functionality or content domain of the API rather than using categories that signal the type of information provided. Instead of dividing documentation into “Samples,” “Concepts,” “API reference” and “Recipes,” the API used in our study should be reorganized using categories such as “Shipment Handling,” “Address Handling” and so on. If developers experience a problem while working with the API and turn to the API documentation to find information that solves the problem, they are likely to know the content domain of their problem (such as shipments or address handling), but it is more difficult for them to predict whether the information they are looking for is presented in the API reference, in a section dedicated to presenting code examples, or in a section discussing concepts. Note that this guideline can be viewed as an application of the principle of minimalist documentation according to which the components of the documentation should reflect task structure (van der Meij & Carroll, 1995).

This is a somewhat radical recommendation because almost all API docs clearly separate out the reference information and label it as such. But perhaps the conceptual and recipe-based information can more easily integrate and re-use information from the reference section in seamless, unified ways. That way if you’re looking for information on Shipping Handling, you might see the relevant Shipping Handling endpoints and parameters as well as tutorials right in the same place (instead of jumping over to Reference for the Shipping Handling endpoint, then back to Recipes for how it might be used, and then over to Concepts for other Shipping Handling information).

It makes sense to have a Reference section where all endpoints are listed, but if this is the only place where these endpoints are described, this pattern might not be most convenient for users.

The authors also recommend that you integrate concepts with their related tasks:

Present conceptual information integrated with related tasks. Another aspect relevant in this respect concerns the integration of conceptual information that developers need in order to use the API successfully. Confirming results reported in Meng et al. (2018), our study supports the conclusion that developers vary with respect to whether they use conceptual overviews that introduce important API concepts in a systematic way. While some developers use such offerings, others tend to ignore them. To reach both groups of developers, conceptual information should not be aggregated in a dedicated section or document that signals to focus on conceptual information. We recommend presenting conceptual information integrated with the description of tasks or usage scenarios where knowledge of these concepts is needed. To give an example from the API used in our test, information regarding the representation of a shipment should be introduced in the section describing how to create a new shipment, and specific features of a return shipment should be provided in the section describing how return shipments are handled.

I love this section because it helps reinforce how poor the DITA information model really is. I don’t want to bring upon the wrath of DITA enthusiasts, who will point out that DITA is a technical schema only and not an information design pattern, but c’mon, DITA’s specialized topics that clearly separate out concept from task from reference and troubleshooting topics here seems like a big fail when evaluating the observations in this article. If you are using DITA, hopefully you can assemble single topics that provide a more integrated approach across these specialized information types.

Conclusion

Overall, it’s great to see the focus of research on API documentation, especially on REST APIs. Although many of the observations seem to echo Carroll’s observations decades earlier about active, experimental learning styles, it’s good info and we still have a ways to go to design appropriately for this learning style.

Your reactions and input

Tell us about your thoughts on this topic. You can see the ongoing responses here.