Is Rhetoric Relevant? Considering the "Message in Context" [Organizing Content #27]

The other day during a boring moment at work I started looking at PhD programs in technical writing and came across the PhD in Technical Communication and Rhetoric at Texas Tech. What struck me was the emphasis on rhetoric. The program description explains that they emphasize "five broad areas of scholarship in its scholarship, coursework, and initiatives: a) Rhetoric, Composition, and Technology, b) Technical Communication, c) Rhetorics of Science and Healthcare, d) Technology, Culture, and Rhetoric, and e) Visual Rhetoric, New Media, and User-Centered Design."

Rhetoric? With all the emphasis on rhetoric, I started to wonder if I was missing something in my day-to-day activities in the workplace. Once when I was in college my dad sent me Aristotle's Rhetoric, and during a lazy holiday break I read it. In Aristotle's sense of the term, rhetoric is the art of persuasion. But not so much political tactics or other underhanded techniques. It's knowing the right way to communicate for the audience and situation.

When academics teach writing and communication, they like to emphasize rhetoric. But the term rhetoric is never formally used in the workplace. In fact, some critics highlight the emphasis on rhetoric as a distinguishing factor that academics are out of step with the workplace. In Editing at School vs. at the Workplace, Don Bush writes,

I would urge professors to pry open a window in their ivory towers and take a good look at practical technical writing and editing. Most of the jobs in industry are in keyboarding. And today there are fewer and fewer of them. “Technical communication” is going online, where the keyboarding is done by the programmers—who, if they have a college degree, have it in engineering or computer science, not in rhetoric. (Feb 2007 Intercom)

Strangely, Bush scorns the relevance of rhetoric while simultaneously emphasizing "keyboarding," whatever that is. Keyboarding seems to be writing and editing, I guess. At any rate, Bush clearly attacks the importance of rhetoric in the workplace.

Thomas Barker is the head of the PhD program at Texas Tech. I wanted to better understand Dr. Barker's use of the term rhetoric, so I wrote to him asking why they chose to use an antiquated term that is almost entirely absent in the workplace.

Dr. Barker replied,

The term rhetoric is meant to evoke the tradition of theory and analysis that underlies academic approaches to communication. As such, it has lots of explanatory power when someone is trying to say why one design works and another doesn't. Besides, isn't it the academic's job to articulate the human and humanistic aspects of a discipline. I would think that workplace practitioners would be encouraged to know that their work has ties with a prestigious tradition that goes back to Aristotle. We do teach the skills you mention, so it's not like our graduates just learn rhetorical theory. But we do it within the context of rhetorical effectiveness with users of technology. (The Academic Conversation)

In other words, the foundation of technical communication is the practice of rhetoric. This rhetorical foundation connects the field of technical communication to a humanistic discipline as old as Aristotle.

Dr. Barker also pointed me to a January Intercom 2010 article he wrote called Rhetoric and Technical Communication. In the article, Dr. Barker explains,

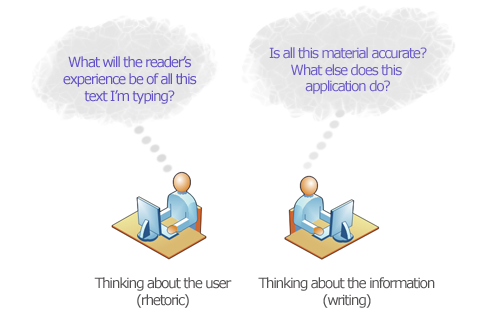

Technical communicators think in terms of message, what we convey to administrators, users, customers, employees, and the public. But what if we pause, step back, and think in terms of the reader's experience with our text? Doing this—thinking about the reader's experience—is thinking rhetorically. Good writers do it naturally. Put simply, rhetoric means message in context. (Intercom January 2010)

In other words, when you start thinking about the reader's experience of your message, that's rhetoric. Considering how the reader will experience your message, and then delivering the message in a way that maximizes the experience you want the reader to have, is practicing rhetoric.

In the university setting, it makes perfect sense to use the term rhetoric, since tech comm departments frequently have to justify their existence and relevance. Any time you can ground your department's purpose with a tradition as old as Aristotle, you have some validity.

Although rhetoric may be the right term in an academic setting, it's an awkward term in the workplace. The term rhetoric in context of the workplace fails "to evoke the tradition of theory and analysis" and "articulate the human and humanistic aspects of a discipline." Instead, if you explain that your role of a technical writer involves rhetoric, most people will think you're in marketing or will simply not understand what you mean.

Instead of rhetoric, the workplace uses other terms, such as user experience, information design, user analysis, engagement, and learning theory, to mean much the same thing. The truth is, regardless of the antiquated nature of the term rhetoric, we professionals would be much better off thinking more about it. To think about rhetoric is to consider your reader's experience of your help content.

Rhetoric is as broad as there are disciplines, and applies to everything from accessibility to reggae music. But in the context of technical communication, there's a specific situation. You're trying to help someone learn a complicated software application or hardware setup. It's a situation of learning. The reader experience you're trying to create is one of understanding and confidence, of knowledge and proficiency.

The reader's experience should be at the forefront of our minds from the beginning of a project. Instead of designing for encyclopedic reference, we should consider how people learn, and integrate learning behavior into the organization, shape, and delivery of help material. We're not creating "documentation." We're creating "communication." And successful communication is grounded in rhetoric.

In short, a consideration of rhetoric would revamp how we deliver help material. It would make us more inclined to deliver screencasts instead of long help files. With rhetoric on our minds, we would be designing easy-to-read quick reference guides instead of 300 page PDF manuals. We would be drawing visual illustrations of concepts instead of writing out endless strings of words that fail to connect with users. eLearning and learning theory would be integral in the way we organize and think about content.

I'm not sure what this rhetorical component should be called in the workplace. For the most part, when people speak of "training" or "user experience," this is what they mean. Training helps put the information you create into a learning context so that users can actually understand and implement the information.

Somehow in all the practice of technical communication, we've forgotten the foundation of it. It's no wonder why most users despise help. It's because the help authors despise and neglect them.