Why simple language isn't so simple: the struggle to create plain language in documentation

Listen here:

You can download the MP3 file, subscribe in iTunes, or listen with Stitcher.

Introduction

In my previous post, When the pain of ignorance exceeds the pain of learning, I argued that users turn to docs only when the pain of not reading the documentation surpasses the pain of reading it. But in this state of mind (when one is impatient, angry, frustrated, high-stress), the user is least likely to absorb the material and learn.

To write for the user in this state of mind, we have to make our docs extremely simple to scan and skim. Among the techniques we can implement, embracing a simple language ranks high as a best practice. While most of us would agree that simple language is the way to go, adopting simple language is much harder in practice.

Here are a few reasons writers don’t often use simple language:

- Writers don’t often realize that their sentences are hard to read

- Writers don’t want to convert their beautiful prose into short, choppy sentences

- Writers are trapped by the language expectations of their discourse community

- Writers want to avoid the appearance of being simple-minded or simplistic

- Writers cannot simplify the language when the discourse consists of new terminology that builds on itself

Writers don’t often realize that their sentences are hard to read

Writers often don’t recognize when sentences they write are hard to read. Sometimes the underlying logic, details, or necessary background to understand the content exist in the writer’s head but are not made explicit in the content itself.

Language checkers can help you identify sentences that are difficult to read. A new language tool for gauging the simplicity of your content is the Hemingway app.

To get a sense of how Hemingway works, paste in any page from your documentation and see what it highlights. In general, Hemingway flags the following:

- Long, complex sentences

- Unnecessary words

- Passive voice

- Adverbs

When Hemingway highlights your sentences in red, it means they are “very hard to read.” The goal of the Hemingway app is not just to encourage simpler language. The idea is that when you remove the excessive adverbs, passive voice, and longwinded constructions, you create bold, clear language that connects directly with users.

Writers don’t want to convert their beautiful prose into short, choppy sentences

Using the Hemingway app to identify difficult sentences can be an eye-opener. You may suddenly realize that a quarter or more of your sentences are very hard to read. But fixing these sentences can be challenging. Simplifying language often means shortening sentences. Shorter sentences tend to sound choppy. If you write in “See Spot Run. See Jane Run” type of sentences, the choppiness is inelegant and can look somewhat ugly and staccato.

Sentences and prose become more rhythmic when you mix up the length — some short, some long. When all sentences are short, and you strip out the introductory clauses, appositives, and conjunctive phrases, the simple sentences start to look a bit like the product of a simplistic writer.

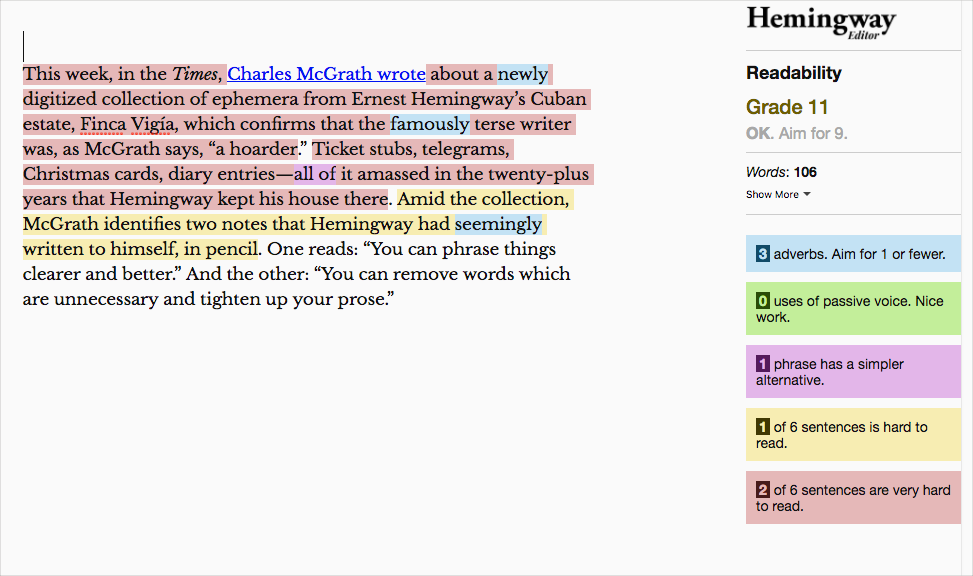

Let’s look an example. In Hemingway takes the Hemingway test, which is a literary critic’s review of the Hemingway app in the New Yorker, Ian Crouch begins his article as follows:

This week, in the Times, Charles McGrath wrote about a newly digitized collection of ephemera from Ernest Hemingway’s Cuban estate, Finca Vigía, which confirms that the famously terse writer was, as McGrath says, “a hoarder.” Ticket stubs, telegrams, Christmas cards, diary entries—all of it amassed in the twenty-plus years that Hemingway kept his house there. Amid the collection, McGrath identifies two notes that Hemingway had seemingly written to himself, in pencil. One reads: “You can phrase things clearer and better.” And the other: “You can remove words which are unnecessary and tighten up your prose.”

Crouch says this paragraph scored an OK with a Grade 11 score in the Hemingway app.

(I suspect the writer deliberately added some complexity to his language to have an example of content that scored poorly. His overall grade level in the article is actually an 8 and scores “Good.”)

The shorter sentences near the end of the paragraph balance out the more difficult sentences at the beginning. If the writer wanted to simplify his writing further, he could recast the paragraph as follows:

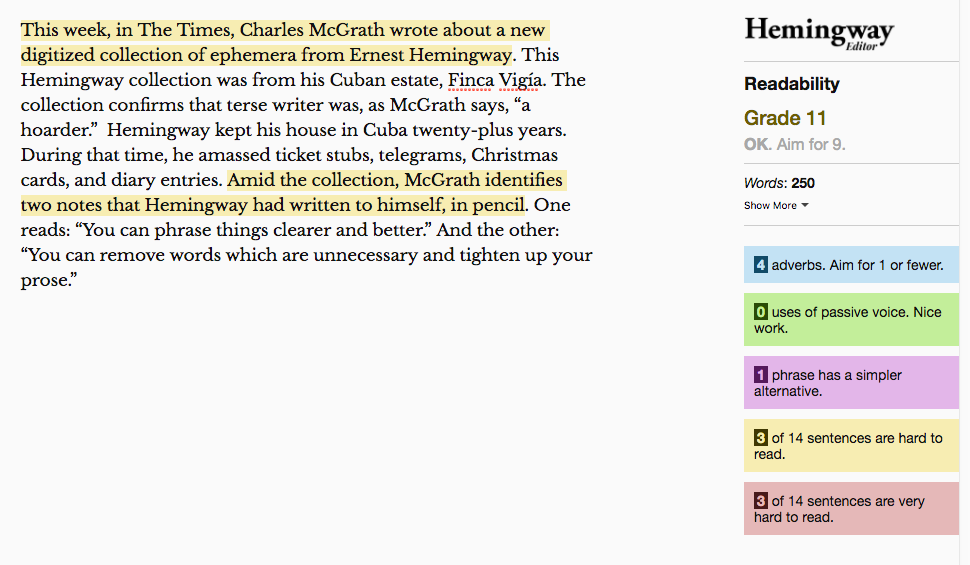

This week, in The Times, Charles McGrath wrote about a new digitized collection of ephemera from Ernest Hemingway. This Hemingway collection was from his Cuban estate, Finca Vigía. The collection confirms that the terse writer was, as McGrath says, “a hoarder.” Hemingway kept his house in Cuba twenty-plus years. During that time, he amassed ticket stubs, telegrams, Christmas cards, and diary entries. Amid the collection, McGrath identifies two notes that Hemingway had written to himself, in pencil. One reads: “You can phrase things clearer and better.” And the other: “You can remove words which are unnecessary and tighten up your prose.”

This version also scores an OK with a grade 11 score, but no sentences are “very hard to read.”

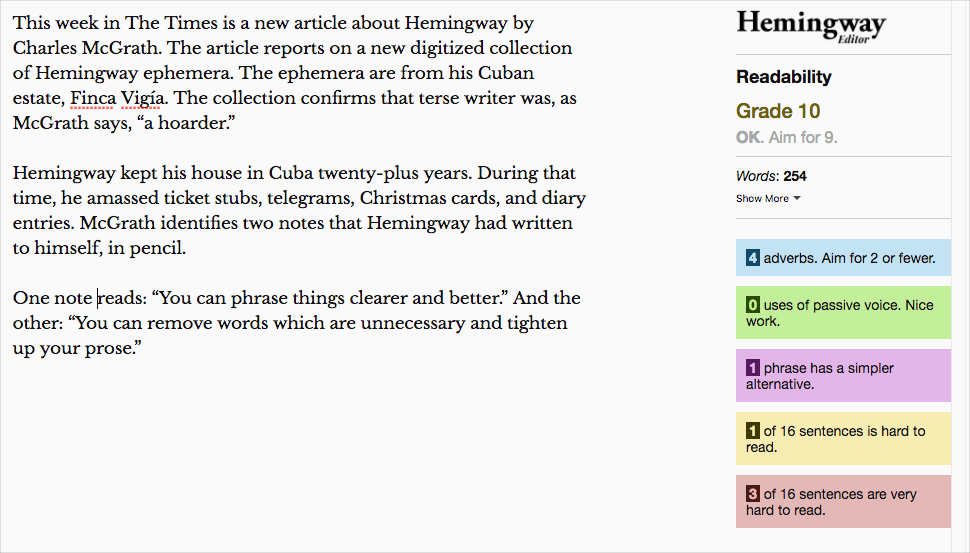

Okay, let’s simplify it even further, removing all hard-to-read sentences and breaking up the long paragraph:

This week in The Times is a new article about Hemingway by Charles McGrath. The article reports on a new digitized collection of Hemingway ephemera. The ephemera are from his Cuban estate, Finca Vigía. The collection confirms that the terse writer was, as McGrath says, “a hoarder.”

Hemingway kept his house in Cuba twenty-plus years. During that time, he amassed ticket stubs, telegrams, Christmas cards, and diary entries. McGrath identifies two notes that Hemingway had written to himself, in pencil.

One note reads: “You can phrase things clearer and better.” And the other: “You can remove words which are unnecessary and tighten up your prose.”

Here we have zero flags with no sentences that are hard to read, and the readability is still OK. The grade level is 10.

It’s hard to simplify it more without eliminating details from the original. In my rewrites, I didn’t omit any information. But simplification is not just about shortening sentences and language. It’s also about taking out unnecessary details, words, and other “fat” from the sentence. With that approach, I would probably cut the first paragraph of that last rewrite entirely.

If you embrace simple language, do you also embrace short, choppy sentences? Near the end of his review, Crouch asks:

But do we want to write like Hemingway? Or, better, did Hemingway really write like Hemingway?”

Crouch argues that Hemingway often broke the rules in the Hemingway app. Despite breaking his these rules, Hemingway still created clear, bold language.

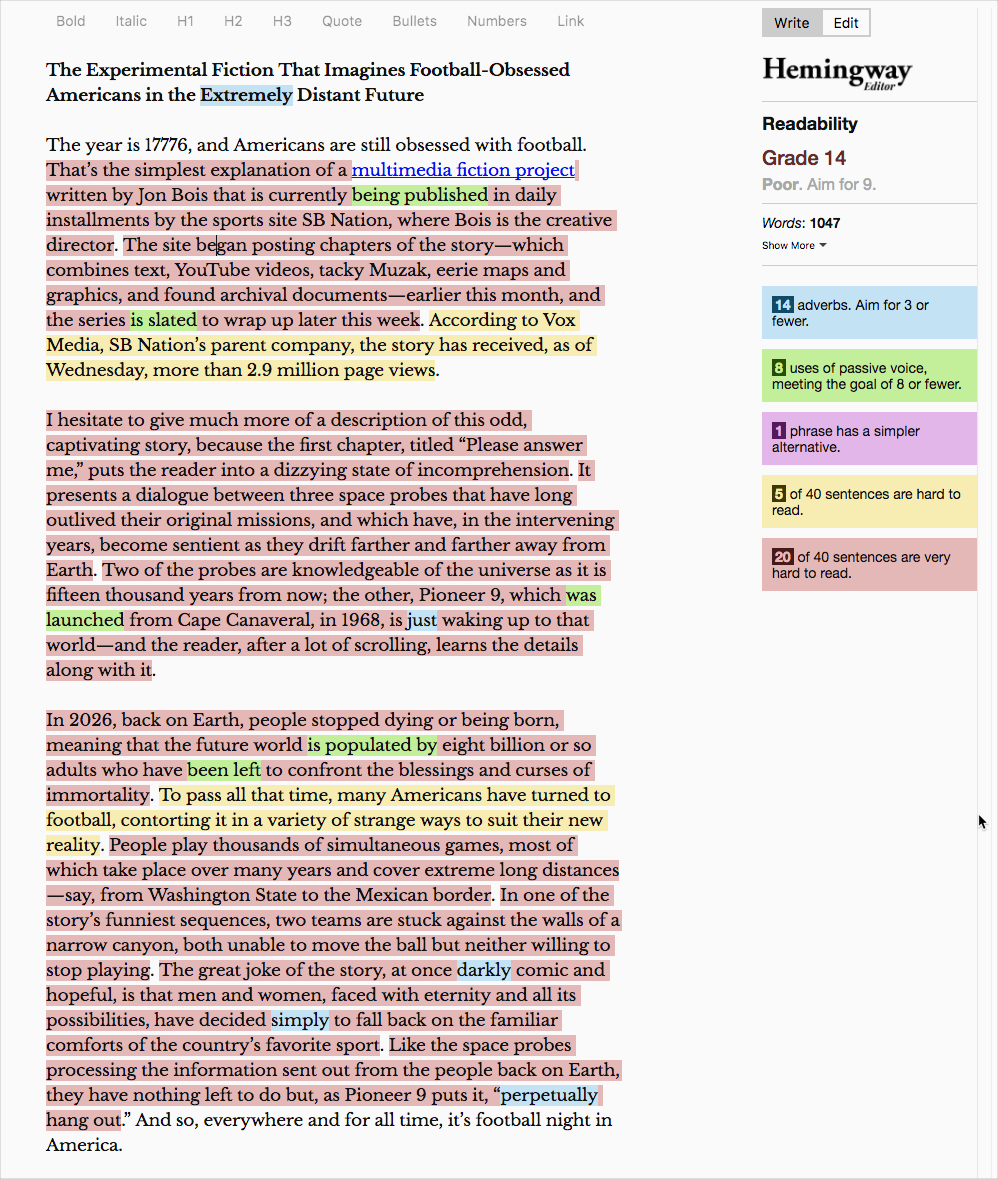

Although Crouch doesn’t explicitly reject the Hemingway app, he seems to disregard it in his future writing. Take a look at Crouch’s latest New Yorker article, The Experimental Fiction That Imagines Football-Obsessed Americans in the Extremely Distant Future.

It seems he abandoned any attempts at simplicity and adopted the normal New Yorker literary style. His article scores a Poor, with a Grade 14. Almost every sentence is “very hard to read.”

Maybe writers don’t embrace simple language because they fear this simplicity will lead to uneducated-looking prose?

Or maybe the idea that short, choppy sentences improve clarity isn’t an idea writers believe. If each sentence is read in isolation, sure the clarity improves. But within a larger context, readers have to assemble these short sentences together in their minds to construct the larger meaning. Longer sentences supply more transitions between ideas. They contain intra-sentence transition words and connectors so readers can see how ideas fit and flow together.

In the end, I suspect that many people agree with the idea of simple language but disagree about its implementation. They are unwilling to make the necessary sacrifices to recast their long, beautiful constructions into short, choppy sentences — especially if you write for the New Yorker. This brings me to my next point.

Writers are trapped by the linguistic expectations of their discourse community

It doesn’t surprise me that Crouch would abandon the simple language recommended by the Hemingway app. He is trapped by the literary conventions and discourse of his environment, the New Yorker.

The New Yorker is considered one of the most elite literary magazines of our day. In the New Yorker, there’s an expectation of elegant prose and sophisticated ideas, woven together with a graceful essayistic style.

This style gets its roots from the personal essay format. This essayist tends to use long sentences with punctuation that creatively weaves together sentence after sentence. The effect mirrors a learned person taking a rambling walk with their thoughts extending through every nook and cranny of the space they traverse.

In other words, in the New Yorker, Grade 14 type prose is expected. If you simplify your language, you risk sounding out of place. Your language would be jarring with the other expected language in the publication.

Writers are trapped by the conventions of their discourse communities. Professors of technical communication, who should be champions of simple language, commit the same crimes against plain language. Take this randomly selected paragraph from the latest issue of Tech Comm Journal:

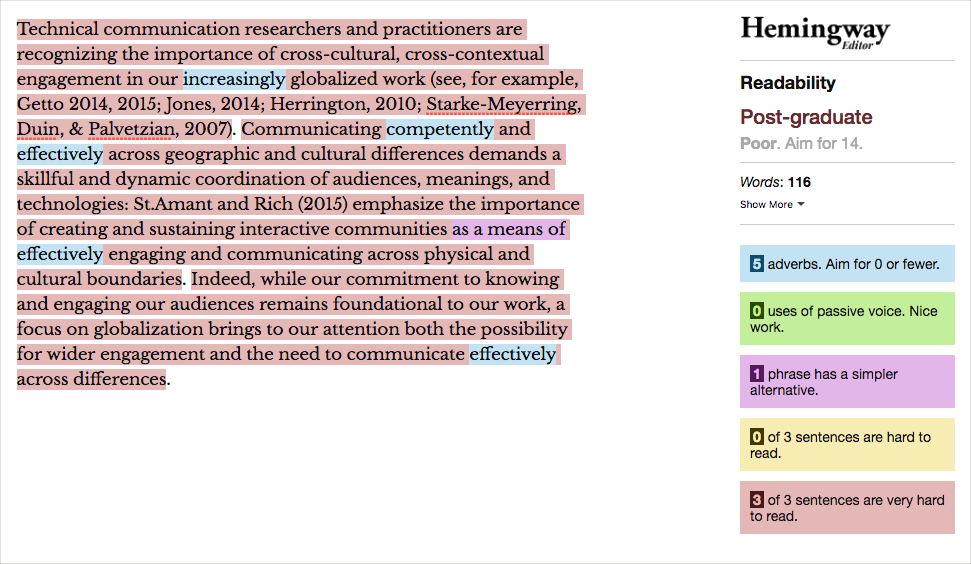

Technical communication researchers and practitioners are recognizing the importance of cross-cultural, cross-contextual engagement in our increasingly globalized work (see, for example, Getto 2014, 2015; Jones, 2014; Herrington, 2010; Starke-Meyerring, Duin, & Palvetzian, 2007). Communicating competently and effectively across geographic and cultural differences demands a skillful and dynamic coordination of audiences, meanings, and technologies: St.Amant and Rich (2015) emphasize the importance of creating and sustaining interactive communities as a means of effectively engaging and communicating across physical and cultural boundaries. Indeed, while our commitment to knowing and engaging our audiences remains foundational to our work, a focus on globalization brings to our attention both the possibility for wider engagement and the need to communicate effectively across differences. Localizing Communities, Goals, Communication, and Inclusion: A Collaborative Approach

In the Hemingway test, this passage scores Poor, with a readability of “Post-graduate.”

For academics, it’s difficult not to slip into the expected discourse. If you read enough academic texts, these polysyllabic words just roll off your tongue:

- practitioner

- cross-cultural

- globalized

- cultural boundaries

- foundational

- engaging and communicating

- physical and cultural boundaries

- communicate effectively

When you immerse yourself in a specific language discourse, it’s natural to parrot it. In this way, academic writing is cyclical. The language breeds itself the more academics read it.

The same happens in other contexts as well. Take religion, for example. When you hear enough people saying prayers, you pick up the language of prayer. Pretty soon, you can start speaking it without any thought. Phrases like “we thank thee for this day,” and “bless the refreshments to nourish and strengthen our bodies” and “bless that we can remember this lesson and apply it in our daily lives” roll off the tongue unconsciously.

Different communities have different discourses. (By “discourse,” I mean special terms, phrases, and ways of speaking.) Communication is a practice of learning and imitating the discourse of your community.

To suddenly break out of the discourse and embrace a simpler form of speech takes a deliberate and conscious act. You have to remove the automatic phrasing from your head. The simplified, frank speech will sound out of place (but also potentially refreshing and new).

Complex language is what’s expected in academic publication. Academics can’t write in simple language and be taken seriously. Similarly, a New Yorker essayist can’t write in simple language and be taken seriously.

Writers want to avoid the appearance of being simple-minded or simplistic

Beyond being pulled into the conventions of a discourse community, writers also adopt hard-to-read language because it makes them sound more sophisticated. I doubt writers would confess that they avoid simple language to avoid coming across as simple-minded or simplistic. But I think unconsciously, this is what is happening.

When you dress up your ideas in complex language, it gives the impression that your ideas are complex. You give the impression that you are complex. In fact, you may even assume that complex ideas by nature require complex language. Or that conversely, by virtue of your complex language, you must be a complex thinker.

Glance back at that previous academic passage. What was it really saying? I’ve read it several times and still have only a vague notion. It sounds somewhat profound, but at its heart, it might just be saying this:

When we communicate with people outside our culture, we have to consider how our language and conventions get interpreted from their cultural perspective.

For example, when someone from another country points with their middle finger, we wonder, is this person subtly flipping me off, or is that just how they point in their culture? Likewise, if we give a thumbs up to show our approval, how does that gesture resonate in the Middle East? Turns out it’s offensive.

If the writer were to simplify the language, the point might sound too obvious and simple. Of course, readers interpret language based on their culture. Of course, we live in a globalized world now and must consider implications of our content in other cultures. What’s the insight here?

Writers don’t always dress up language with more complexity to sound smart. Other times, they’re just trying to clarify their thoughts. They don’t have a firm grasp on the ideas they’re trying to express, so they use meandering prose (filled with adverbs, parentheticals, multiple punctuation, and synonyms for the same meaning). Through it all, they struggle to articulate a fuzzy idea. The result is complex language and vague meaning.

Writers cannot simplify the language when the discourse consists of new terminology that builds on itself

Documentation isn’t trapped by academic style or New Yorker literary style. The language of documentation is informed by industry-standard style guides that are Hemingwayesque. Sure, there is a mild documentation style to learn. You “click a button” and you “select from a drop-down list.” Little circular options are called “radio buttons,” and so on.

For the most part, style guides help create a discourse of simple, readable language. It’s a discourse that, for all the negative attention documentation receives from users, other disciplines would benefit from.

However, the discourse of documentation is hampered by more fundamental problems than the New Yorker style or academic style. Whereas literary aficionados and academics could, if they desired, probably simplify their language and communicate in plain-style speech, it’s much harder with technical documentation.

Technical documentation might use a simple style, but it introduces its own set of hard-to-understand terms that make the style issues seem trivial by comparison. In a way, technical documentation is a foreign language — much more than simply a different discourse style. (In fact, most colleges give students foreign language credit when they take computer programming.) User frustration is often due to not speaking the technical language of the documentation.

Here’s an example. In the Android Developer docs, an “Intent” is described as follows:

An intent is an abstract description of an operation to be performed. It can be used with startActivity to launch an Activity, broadcastIntent to send it to any interested BroadcastReceiver components, and startService(Intent) or bindService(Intent, ServiceConnection, int) to communicate with a background Service.

An Intent provides a facility for performing late runtime binding between the code in different applications. Its most significant use is in the launching of activities, where it can be thought of as the glue between activities. It is basically a passive data structure holding an abstract description of an action to be performed. (Intent)

The writer uses a simple style. And the passage scores OK with Grade 13 in the Hemingway app. But it’s hardly understandable. The incomprehensibility is not due to the stylistic constructions. It’s due to the unfamiliar terminology. This documentation requires readers to learn a new vocabulary. Behind the new terms is often a new concept as well.

No matter how you try to simplify it, users unfamiliar with the terms and concepts will find this documentation impenetrable.

The terminology builds on itself. Understanding an Intent is foundational to understanding a “PendingIntent.” What’s a PendingIntent? The technical writer describes it as follows:

A description of an Intent and target action to perform with it. Instances of this class are created with getActivity(Context, int, Intent, int), getActivities(Context, int, Intent[], int), getBroadcast(Context, int, Intent, int), and getService(Context, int, Intent, int); the returned object can be handed to other applications so that they can perform the action you described on your behalf at a later time.

By giving a PendingIntent to another application, you are granting it the right to perform the operation you have specified as if the other application was yourself (with the same permissions and identity). As such, you should be careful about how you build the PendingIntent: almost always, for example, the base Intent you supply should have the component name explicitly set to one of your own components, to ensure it is ultimately sent there and nowhere else. (PendingIntent)

The sentences aren’t New-Yorker-style long. Nor is the language saturated with polysyllabic words as with academic texts. But the terminology builds on an understanding of other terms. To understand a PendingIntent, you have to understand an Intent. To understand an Intent, you have to understand a startActivity. To understand a startActivity, you have to understand an activity and runtime binding.

While an activity may seem like it’s defined easily enough (“An activity is a single, focused thing that the user can do”), in the context of Android, its meaning differs from Webster’s definition of an activity, which is “the quality or state of being active / behavior or actions of a particular kind.” Now the user not only has to learn a new term, the user has to assign multiple meanings to the same term.

The problem of simple language is more difficult with technical documentation (particularly developer documentation) than it is with other discourse communities. With technical documentation, many of the words in the language itself are new and interrelated, as well as the concepts. It’s a new language users need to speak, not just a style for familiar words to fit into.

Solutions to the terminology problem

There’s no easy way around the terminology problem. If you explain technical words and concepts in a way that novices can understand, you put off advanced users who already speak the language and have the necessary vocabulary background. For example, if the Android developer docs were written with novices in mind, they would be 2-3 times longer than they currently are. Do you sacrifice concision for one audience to gain clarity with another?

Technical writers often find themselves in impossible situations. You can write for novices, or you can write for advanced users, but it’s difficult to do both at the same time. Your approach will be sure to frustrate one or the other. And you also can’t feasibly create two versions of the documentation. You don’t have the bandwidth.

As a result, you have to choose the audience you want your content to connect with.

The question of addressing both advanced and novice users with the same set of docs is an age-old conundrum in technical communication. One solution is to choose a language that the majority of your users presumably understand. In Content Audits and Inventories, Paul Ladenburg Land defines simple language as follows:

A document, website or other information is in plain language if the target audience can read it, understand what they read, and confidently act on it. (9.5. Plain Language)

This means even language that scores “post-graduate” with a grade level of 15 in the Hemingway app, implementing advanced terminology and concepts, can be considered “plain language” — so long as the audience can read and understand it.

Land gives the following advice for balancing expert and novice content:

Sites aren’t always easily divided into expert vs. novice content (nor should they be), so be aware that novices can come across technical content. You don’t want all the expert-level content written in such a way that it doesn’t meet novices’ needs, but look for ways that novices can easily navigate to more information and not get stuck at dead ends.

For the expert user, the goal is likely for the content to focus more on making her feel well informed and to offer ways to increase her expertise. If the expert user is a decision maker or if the product appeals to users who already have a high level of knowledge, the user may not need much assistance content but may need comprehensive, specific, accurate information – and may need to find it quickly. Navigation and copy should expressly support this focus by being as brief as possible, and by using precise, concrete, to-the-point language. (9.6. Expert vs. Novice)

In other words, if possible you should separate expert and novice content. But ultimately, you write more for experts, with some helpers for novices.

Glossaries and tooltips as help for novices

Providing a glossary is a good first step in helping users understand your content. When you provide a glossary with your docs, you give users a way to learn your system’s language. Further, when you can gracefully link unfamiliar terms inline with tooltips or glossary references, you make those terms available to the user at the time the user needs them.

Weaving these tooltips into your documentation manually is tedious and prone to error. If you link every instance of the term Intent, PendingIntent, Activity, startActivity, and broadcastActivity to their corresponding glossary pages, and even link glossary definitions that define one term with another, you end up with a lot of links.

The abundance of inline links can be distracting and paradoxically make it harder for users to read the content. Each link presents a jumping off point, and users must constantly make decisions about whether to click links or not. Still, if you can pull off an inline glossary, especially in an automated way, I think it’s a good move.

Whether people use the glossary is also debatable. Coming back to the impatient, frustrated user who searches for an answer — will he or she take the time to learn the necessary vocabulary before reading your documentation? Probably not, and the docs will seem like gibberish. But at least you’ve given the user a lifeline to grab hold of in the water. There’s now a clear starting point to avoid drowning.

Conclusion

In developer documentation, the struggle for creating simple-to-read documentation is two-fold. First, technical writers have to learn this technical language so they can speak it effectively in the user’s discourse community. For example, if you’re describing a sample Java app, you have to be conversant in Java lingo and conventions so that other Java developers can understand you. You also have to recognize the language so that you can evaluate and edit any content that your Java engineers provide to you.

At the same time, you have to be sensitive to users who may not be conversant in this language. If you’re a novice, you can probably spot the areas of confusion more easily than engineers. In these areas of confusion, you can link to glossary terms and provide other helps for new users.