Preferring technical acuity over specialized knowledge

Listen here:

You can download the MP3 file, subscribe in iTunes, or listen with Stitcher.

The unresolved debate between being a specialist or generalist

After I gave a recent presentation on trends, some of the attendees felt I left the dilemma between being a specialist or a generalist unresolved. Some said, “So, should I be a specialist or a generalist, and if I specialize, what should I focus on?”

Others were incensed that I wasn’t considering language expertise to count as specialized knowledge. I knew this was a controversial subject, and I would no doubt anger people off because to suggest that their writing expertise doesn’t count as specialized knowledge in the same light as engineering specializations.

So there are a few loose ends that I’d like to resolve in this trends presentation before I give it again. Overall, in the Q&A after my session, attendees seemed to come to the conclusion that technical acuity was more important than specialized knowledge, and that it was better than being a generalist as well. In hindsight, my portrayal of the dilemma between being a specialist or generalist was an either/or fallacy. A third option — “technical acuity” — wasn’t something I weighed and considered.

What is technical acuity?

What do we mean by “technical acuity”? Someone with specialized knowledge might know Python in and out, but someone with technical acuity possesses a technical mindset. With this technical mindset, he or she might be inclined to look at system inputs and outputs, at algorithms that drive application logic, or more. Maybe he or she has a systematic patience for troubleshooting by comparing working code against broken code in a line-by-line fashion, or other troubleshooting insights.

In other words, the person with technical acuity might not know Python (perhaps what a hiring manager wants), but his or her in-depth knowledge of C# and, say, big data analysis might have prepared the person with the technical mindset needed to grok the Python info that’s needed in a particular project.

Why technical acuity over specialized knowledge?

Why might technical acuity be more valuable than specialized knowledge? Well, specialized knowledge in a particular subject domain is often difficult to find in candidates. For example, suppose you really want a tech writer who knows Android. Well, try as you might, there are so many different knowledge domains out there, the chances that the technical expertise in your candidate would align perfectly with your needs is pretty unlikely. This is especially true for technical writers, who often have a variety of projects involving different technical specializations.

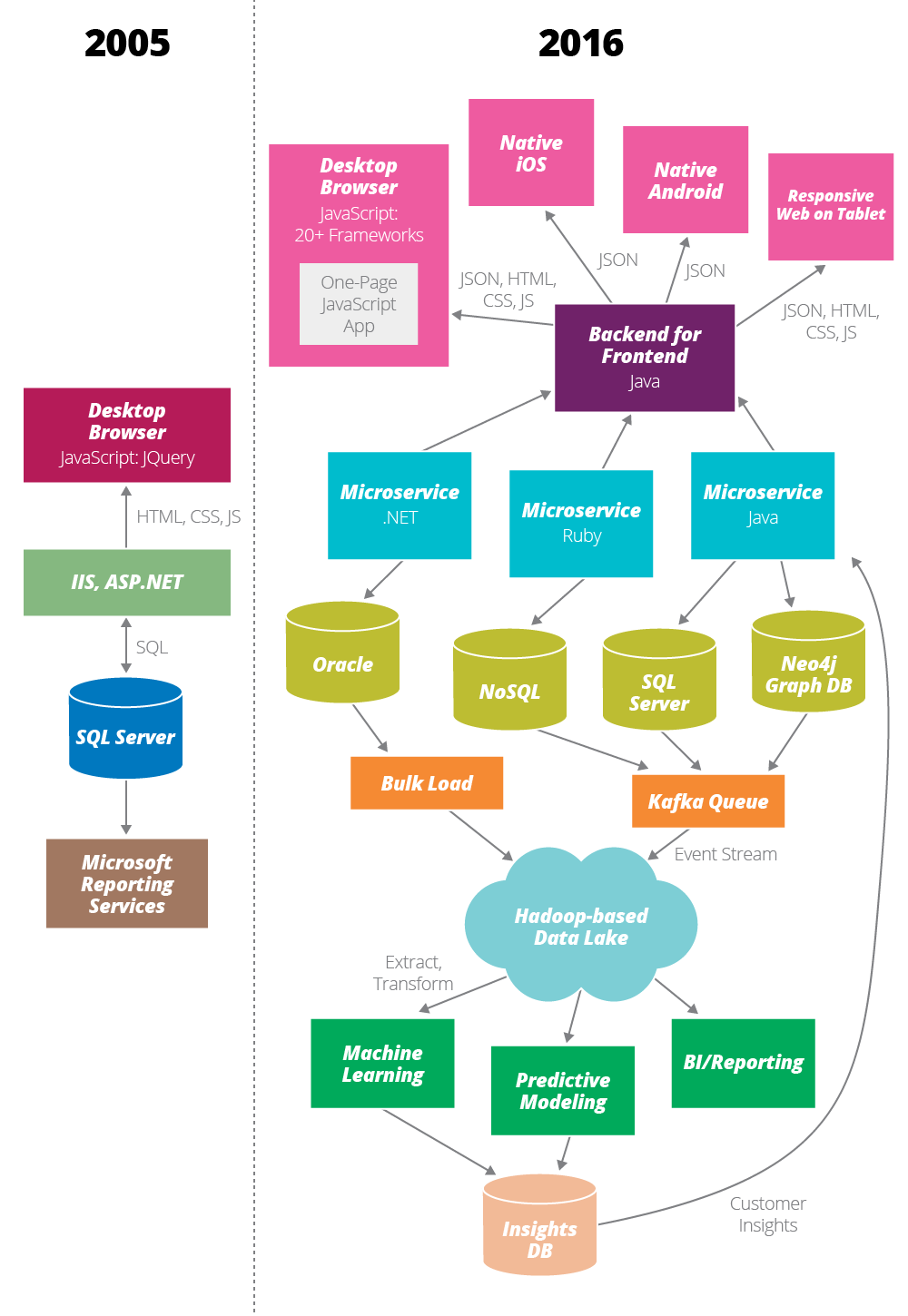

For an example of the needed variety, look at this explosion of technologies between 2005 and 2016 as depicted by Thoughtworks:

In the transition from single vendor technology stacks (e.g., Microsoft) to multi-vendor stacks, it’s impractical to hire individual specialists to handle every unique component. Instead, engineers need to be able to traverse the tech stack as needed and self-learn what they need to know. What’s more valuable in this explosion of technology? Someone who knows 2-3 of these boxes in depth, or someone with strong technical acuity (who might only know 1 box) but who can ramp up and make sense of a dozen boxes in a few months?

Preferring technical acuity over specialized knowledge isn’t a hard argument to swallow. This is the same argument tech writers have been making about tools for ages. We’re all coached to answer job interview questions this way — “I might not know Tool X, but I know Tools Y and Z, so I’m pretty sure I can pick up Tool X quickly.”

If we believe technical acuity, do we believe in writing acuity?

Strangely, we don’t always accept the same arguments about writing. What if a candidate were to say, “Well, I don’t know the details around technical writing, but I’ve written several plays.” Or, “I’ve never done technical writing before, but I was once the poet laureate of my town!” Or in reverse, “I haven’t done grant writing before, but I’ve done plenty of technical writing.”

If technical acuity would allow for potential competence across technical domains, why shouldn’t writing be the same? After all, aren’t we addressing a similar rhetorical situation in these other writing domains? Aren’t we negotiating our language strategies as we consider audience and purpose? Isn’t this “writing acuity”?

We don’t care if one is an excellent medical writer, but rather we want to know if they can analyze their audience’s information needs, whether they can identify the genre discourse and rules and write within that construct. We want to know if they can anticipate the audience’s objections and have a conversation (real or imagined) with the audience in order to drive the content. Understanding of rhetoric is basically writing acuity, which is why tech comm programs teach rhetoric to students.

Sure, someone might have good rhythm in their sentences and a solid grasp of grammar, but that’s not necessarily writing acuity, in the same sense that understanding graph packages in Java might not constitute technical acuity.

“Are you technical?”

This discussion about technical acuity takes me back to one of my first technical writing jobs. The job involved documentation for a network engineering project. The hiring engineer basically wanted to know whether I was “technical.” I felt I was pretty technical, though as the weeks on the job went by, I realized that I wasn’t as technical as the engineer had hoped. I scrambled to become more technical, as I read books on network engineering in an effort to understand what I needed to document in a multi-million dollar storage array.

His question, “Are you technical?” seems like a good question. But it can be interpreted in so many ways. I tried to remind the engineer that I knew a ton about some technical topics (e.g., WordPress theming, RoboHelp, and more) and that he was being unfair to question whether I was technical or not based on my understanding of RAIDs in storage arrays.

One can be technical even with language or non-code topics. What if I can diagram complex sentences using advanced grammar terminology that labels 16 different elements? Is that technical? What if I can disassemble my bike’s crankshaft and then reassemble it with all new parts? How about if I can swap in a new motherboard in my computer? Does being technical in one category really transfer to technical abilities in other categories?

Whether technical acuity allows you to operate across technical domains is an interesting question. For sure, the technical mindset is only the beginning. One has to apply that mindset to study and learning for the subject knowledge needed in that new domain.

How I’m trying to improve my technical acuity

Overall, I’m persuaded by this argument about technical acuity, so I’ve decided to be more diligent about completing my “tech pomodoros,” as I call them. These are 20-minute sessions where I try to learn some technology. It usually ends up being related to work tech, so lately I’ve been trying to improve my knowledge of Alexa. (Look for some forthcoming flash briefing skills on my blog, hopefully.)

I made a goal to complete three tech pomodoros the first thing of the day when I come to work. (I consider ramping up my technical acuity a kind of on-the-job training, part of the needed regiment to stay current as a technical writer working in developer docs.) My life seems to get so busy, if I don’t knock these pomodoros out first thing, the day’s tasks and busy-ness entirely consume me.

We’ll see how long I can keep it up, as it does make me less productive at work, but in the long run, I feel it sharpens my mental wheels and makes more capable. It puts me into a learning mindset, which I find useful for the technical writing role. The whole effort reminds me of a common quote from Lincoln, “If I had 8 hours to chop down a tree, I would spend 6 of those hours sharpening my axe.”

Here’s a short poll to see if you agree:

You can view the poll results here.