Related video and audio

Here’s a video of a presentation I gave on this topic in May 2019:

Listen to this article:

You can download the MP3 file, subscribe in iTunes, or listen with Stitcher.

For details about the presentation, see this post.

Bloggers and trends

As a blogger, I’m conscious of my web analytics (whether metrics from clicks on newsletter articles or visits to pages), since I’m keen to know what topics resonate with readers. Each year I look deeply at analytics and try to gauge what topics I should focus on — partly to drive more traffic, and partly out of simple curiosity to know what readers click on most. Without a doubt, one topic that gets the most clicks, year and year out, is trends.

Exactly why the topic of trends is so popular, and whether bloggers have any special insight about trends, remains a bit of mystery to me. I’ve never considered myself an expert on trends, though after I posted my 2018 trends, I literally had three separate groups invite me to speak on the topic. I’ve noticed that in general, people frequently associate bloggers with the topic of trends, as if trends were intertwined with the blogging brand.

I’ve never really dug into trends with any depth because they seem so speculative and elusive. But for once, if only to satisfy this appetite that people seem to have for bloggers to write about trends, I’d like to dig into the topic of trends with some in-depth research, analysis, and hard thinking. So sit back, hold onto your hat, and get ready for a ride deep into trends territory.

Why trends intrigue us

In a rapidly changing field like technology, almost everything is in constant flux. Sometimes you wake up and so much seems to have changed. Consider how previously dominant companies simply vanished: Blackberry, Blockbuster, Borders Books, Toys ‘R’ Us, Kodak, Radio Shack, Tower Records, Circuit City, Encyclopedia Britannica, and others. We woke up one day, checked the Internet, and probably thought, what happened? Why did they fizzle?

Some say these companies fizzled because they focused only on what helped make them successful and became blind to further innovation after achieving success (see “Companies That Went Bankrupt From Innovation Lag”). This is generally called the Innovator’s Dilemma — you have to keep disrupting your innovations, even if it poses risks.

I’ve only listed companies, not job roles. But couldn’t the same be same of technical writing professions? Look at the constant evolution of tech comm ideas. At the turn of the century, we moved from PDF to web formats, then gradually to DITA and the semantic web. Then wikis became popular, and later YouTube. Later, content strategy surfaced, and almost overnight, many tech comm titles changed. Augmented reality peers its head in once in a while, but not seriously. Lately, chatbots have taken center stage. Who isn’t building a chatbot? :) Entire conferences were organized around chatbots, and many felt this was the future of documentation, though some disagreed. Now docs-as-code tools seems to be getting the most attention, as tech pubs follows software engineering workflows.

Ideas and technologies come and go. How do you know whether a trend today will be the norm tomorrow, or whether the trend will just fizzle out? Should you realign your docs into consumable chunks for chatbots? Or switch from DITA to Hugo? Or just hold back and wait and see, hoping you aren’t left behind while waiting?

We pay attention to trends partly out of curiosity but also to stay relevant. We don’t want to wake up one day, find a pink slip on our desk, and ask “What happened?”

But understanding whether trends will become the norm requires us to investigate the evidence for the trend. What data supports a trend? When Blockbuster looked at the emergence of streaming online video, or when Kodak looked at digital photo formats, did they dismiss these trends as fads? How can you find evidence for what the future will hold? How do you move past wild and fun speculation into meaningful data that supports the direction you should take?

The impact of UX and the need for documentation

We need a starting point for this discussion on trends, so let’s start with some assertions in a recent episode of the Cherryleaf podcast, 40. The evolution of the technical communicator’s career. In the podcast, Ellis Pratt discusses an article called Software technical writing is a dying career (but here’s what writers can do to stay in the software game), by Jim Grey published in 2015.

Grey’s argument is that “companies are leaning into good user-interface design and stepping away from online Help systems and printed/PDF documentation.” Grey explains that he had lunch with a business owner who explained this transition, saying that most startups these days are hiring UX designers, not technical writers. Grey writes:

Technical writing is dying off…. It’s all about clean, engaging UX now. I have talked to more than a hundred startup and small software companies as I’ve built my business. Almost none of them have technical writers, and almost all of them have UX designers.

Sensing the irrelevance of technical writing, Grey jumped off the documentation ship and into software testing instead. As a software tester, he still leverages many skills he learned as a technical communicator.

Undeniably, User Experience Design has matured as a discipline. Companies like Apple have cemented the idea that users are willing to pay for well-designed products that don’t rely on much documentation. But does it mean companies are eliminating tech writers from their organizations? Does Apple have ten times as many UX designers as technical writers?

To evaluate whether tech writing jobs are dying off, let’s dive into some data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). According to the latest STC Salary Database (based on BLS data), tech writing jobs have grown by about 3,620 jobs in 4 years:

In 2016, there were about 50,000 technical writing jobs in the United States. The report notes that technical writing is “the only occupation [among professional writing disciplines] which has seen employment growth in each year since 2011, with an average annual employment increase of 1.9%.”

Despite the growth, technical writing jobs aren’t necessarily keeping pace with software development jobs. The BLS says the job growth for software developers from 2016 to 2026 is projected at 24%, but for technical writers, the job growth is projected at just 11%. (Both growth rates are higher than the national average, which is 7%.)

To put these numbers into perspective, suppose that in 2016, 10 technical writers support 1,000 engineers. In 2026, 11 technical writers will support 1,240 engineers. If the rate stays the same for the next decade, in 2036, 12 technical writers will support 1,538 engineers.

So while technical writing jobs might not be diminishing, they are shrinking proportionally. The data doesn’t provide more granularity to address other questions, such as whether jobs are growing or shrinking in different specializations (such as API documentation versus UX copywriting). There’s also a possibility that technical communication job titles have diversified and made BLS’s scope too narrow. However, the BLS does try to “ensure employees are appropriately slotted into the correct occupation as job titles often vary widely from company to company.”

At any rate, as far as reasons for growth within the tech comm profession, the BLS has little to say except this:

Employment growth [in technical writing jobs] will be driven by the continuing expansion of scientific and technical products. An increase in Web-based product support should also increase demand for technical writers. Job opportunities, especially for applicants with technical skills, are expected to be good.

I’ll return to this last point — “especially for applicants with technical skills” — a bit later.

An “evolution” of roles, but evolving towards what?

What does Pratt make of Grey’s blog post? In the podcast, Pratt looks generally at job trends and decides that no, technical writing jobs haven’t gone away. Pratt’s company, Cherryleaf, is primarily a recruiting agency for technical writers, so the mere fact that he’s still in business suggests that companies are still seeking technical writers.

But Pratt does make another point. He says that jobs might not be going away, but the role is evolving:

Is this true? Has the tech writing job disappeared since 2015? Clearly not, because there are still … [many] technical writers and authors. But I think there is a truth in saying that the role of the technical author is changing, and the requirements and the skills that they need are changing as well. And it may be that the job title changes and the way in which the role is perceived.

Most readers tend to agree with Pratt that the tech writer’s role is evolving. In a survey I conducted in a previous post, I asked readers to state their level of agreement about whether the tech comm profession is evolving. Of the 65 respondents, about 53% of readers agree and 39% strongly agree (for a total of 92% agreement). Given that change is the only constant, how can anyone disagree that the tech comm role is likewise evolving?

But exactly how is tech comm evolving? Towards what direction? Are we changing in positive ways to align with tomorrow’s needs? Are we being left behind? And what kind of data supports these changes?

To get a better picture of evolution of the tech comm role, let’s turn to some research based on an analysis of job advertisements. In “The Evolution of Technical Communication: An Analysis of Industry Job Postings,” Eva Brumberger and Claire Lauer look at patterns in job advertisements to determine what skills employers are looking for. They say that that genre of job advertisements “can serve as a barometer of industry trends when studied over years and even decades.” In other words, if employers aren’t seeking the skill, it’s probably not an important trend.

After analyzing about 1,000 job postings in late 2013, Brumberger and Lauer found that the job landscape painted a picture far more diverse than the BLS’s simplistic description of the technical writer occupation. The authors noted the incredible variety of roles and deliverables that tech comm professionals are engaged in.

Part of this diversity is a result of Brumberger and Lauer’s broad focus on job technical communication titles and categories. Some of the job titles include “Social Media Manager,” “Front End Developer,” “Web Content Analyst,” “UI Designer,” “Grant writer,” “Medical writer,” and more. Given this wide tech comm net they cast, it comes as little surprise that they would find tech comm professionals engaged in such a variety of work.

Fortunately, they divide the job postings into five main categories: Content Developer/Manager, Grant/Proposal Writer, Medical Writer, Social Media Writer, and Technical Writer/Editor. Although this wide scope is probably appropriate for a tech comm program, my interests relate mostly to technical writing, so I’ll narrow my focus on this “technical writer/editor” category in Brumberger and Lauer’s study (this category makes up 52% of the total job ads).

According to Brumberger and Lauer, the most sought-after professional competencies for technical writers/editors include written communication (75%), Editing (51%), Project planning/mgmt (49%), Visual communication (49%), Subject-matter familiarity (45%), Working with SMEs (41%), and Style guides/standards (40%).

Commenting on overall trends across the job categories, the researchers observe the need to push content across multiple channels while adhering to brand, and the need to build relationships with customers through content. The authors also deliberate about whether to specialize with more subject-matter familiarity. They say this emphasis on subject-matter familiarity is particularly relevant in technical writer/editor job categories.

Given the broad range of skills, roles, and deliverables within the umbrella of technical communication, the authors argue that remaining a jack-of-all-trades generalist would give you a lot of mobility and versatility within the field, empowering you with capabilities in a lot of different roles and functions (perhaps switching from technical writer to medical writer to social media manager).

However, Brumberger and Lauer acknowledge that others see specialized knowledge as being more valuable. The authors reference another study by Craig Baehr who interviewed a small handful of experts from STC’s Advisory Council. Baehr’s goal was to identify the core skillsets that define what it means to be a technical communicator.

Baehr found that perspectives on specialization versus generalization were mixed among the council members. Some argued that the generalist skillset would “permit technical communicators to be more agile, adaptable, and flexible in their roles and to add greater value to organizations.” Other said specialization was “inevitable.” Baehr found that the most common specializations were related to “information design, knowledge management, and information architecture” (which differs from subject-matter familiarity somewhat).

Baehr argues that “breadth of specializations” define the core identity of technical communicators. He concludes that “successful technical communicators adapt to fit the mold of what is needed.”

Aligning with Baehr, Brumberger and Lauer also find middle ground in the dilemma between being a generalist or specialist. They say,

Our data suggest that there are several points of overlap in products and competencies, which could allow some degree of movement among job categories — or multiple specializations — if one maintains a broad skillset and flexible outlook.

In other words, they choose multiple specializations and a broad, flexible skillset as the best approach, especially where the specializations might strategically overlap into multiple roles. By arguing for multiple specializations where “there are several points of overlap”, the multiple specializations shouldn’t be interpreted to be roles diverse as project manager and engineer and UX designer (then you’d really have the market cornered!), but rather combined specializations such as information design and SEO and information architecture. Or API documentation and programming languages and docs-as-code tools. Or UX copywriting and content strategy and web analytics.

Other academics have also analyzed job advertisements to infer trends. In “Analysis of the Skills Called for by Technical Communication Employers in Recruitment Postings,” Clinton Lanier analyzed 327 job postings in 2006. He limited the scope to jobs with “technical writer” in the title that required just two years of experience or less (which would thus be most suitable for graduating students to apply for). Regarding subject matter familiarity, Lanier found the following:

… 112 of the postings (34%) required or desired the potential writer to have experience writing about the specific subject matter that the current job involves. [For example], if the candidate was applying for a software documentation job in which they were going to be writing application programming interfaces (APIs) or online help, many of the positions required or desired that they have written such types of documents for the related types of subject matter.

In other words, employers have been seeking subject-matter familiarity among job applicants in a consistent way at least since 2006. Even for job postings requiring just two years of experience or less (almost entry-level positions), 34% of employers want the candidate to have subject matter familiarity. Lanier explains:

This reflects the trend that technical communication is moving away from a “Jack of all trades” model, where technical writing is a very generalized concept, and toward a model that is more specialized and contextually defined.

Given that Lanier restricts his data set to jobs requiring two years or less of experience, it’s hard to compare the data set with Brumberger and Lauer’s. However, 34% in 2006 and 45% in 2013 suggests a constant emphasis on subject-matter familiarity. Deciding to specialize in a particular engineering domain wouldn’t be considered a new trend, but its consistency for the past 15 years suggests that it’s an ongoing requirement. It’s not a fad but rather a norm that one must adjust to in order to excel in tech comm.

Career experience as a factor

Whether to specialize or not seems to draw mixed reactions and emotions. So far I’ve argued for some middle ground, but let’s dive a bit deeper to note other factors that might determine whether one becomes a specialist or generalist.

In a Content Strategy podcast, IA professional Abby Covert says that junior IA positions are more generalist while senior IA positions are more specialized. A junior IA starts out doing generalist UX tasks for about 5 years, and his or her job title might not even include “information architecture.” After the person becomes more senior, he or she might start doing more IA specific tasks and have IA in the job title. Covert explains:

So I’m really seeing a misbalance of information architecture as a specialty being only those that are in the mid or senior levels of their career. Which I think is challenging because it’s kind of like “Hey kid, I know you really want to be in IA, wait 5-7 years as a generalist and maybe you can be.”

The same pattern might apply to tech comm roles. When you’re new to the field, you work on a wide variety of documentation-related tasks that define the generalist’s breadth of skills. You might work on UI copy, reports, documentation for new features, presentations, analytics, blog posts, edits of existing topics, SEO, doc site design, and more.

But as you become more experienced, you might focus exclusively on revamping the doc publishing system, or in producing a lengthy e-learning system, or creating API documentation, etc. You could become even more specialized — migrating thousands of pages to DITA from unstructured FrameMaker, implementing Swagger UI custom skins, or documenting Java programming SDKs. In this sense, one might say there’s a time to be a generalist, and a time to be a specialist. Both characterizations of the profession are valid.

Industry as a factor

Whether you’re a generalist or specialist might be based on the industry as well. With API documentation, James Neiman, an experienced API tech writer in the Bay area, says that you need an engineering background, such as a computer science degree or previous experience as an engineer, to excel. Neiman says tech writers often need to look over a developer’s shoulder, watching the developer code or listening to an engineer’s brief 15-minute explanation, and then return to their desks to create the documentation. You might need to take the code examples in Java and produce equivalent samples in another language, such as C++, all on your own.

Here’s a video of Neiman and Andrew Davis (a recruiter for API tech writers in the Bay area) presenting on Finding the right API Technical Writer at an API conference in London. Their presentation format includes a Q&A exchange between the two. Scrub to around the 22-minute mark for the relevant part:

Neiman explains,

There is no way that a busy engineering team has time to train a person without a computer science degree. That’s just the reality of it. Engineers at best can speak to you in some version of English, which may or may not be their native language. They don’t have a lot of time, and they expect you to finish their thoughts for them. That means that you need to be able to sit next to them and look at how they’re coding, and then be able to replicate that and extend it and even create examples.

Other tech writers in the API doc space push back on the need to develop deep engineering knowledge. It takes a lot of time to accrue engineering knowledge, and that time cost means neglect in other areas. James Rhea explains:

I speculate that the need for writers to have deep technical knowledge diminishes as Tech Comm teams grow in size and as other skills become more important than they are for smaller Tech Comm teams. I’m not claiming that deep technical knowledge is useless. I’m suggesting that (to frame it negatively) neglecting deep technical knowledge has less severe consequences than neglecting content curation, doc tool set, or workflow considerations.

In other words, if you spend excessive amounts of time learning to code, at the expense of tending to other documentation-related tasks (like fixing your stylesheets and looking at analytics and improving your navigation), your doc’s technical content might improve a bit, but the overall doc experience will go downhill.

I like the middle ground approach that Parson, a tech comm consultancy, describes:

The tasks of the technical writer in API documentation projects depend on the writer’s programming skills. There are technical writers who are able to write code samples and sample programs themselves. Programming knowledge is very useful, especially for complex software products. However, it is not mandatory to be a software engineer yourself, if you want to write documentation for software engineers. It is mandatory, however, that you have a solid understanding of software programming, of object-oriented programming languages, and of modern development methods, such as agile.

The strengths of technical writers, and thus the real benefit for API documentation projects, lies elsewhere: technical writers are able to structure information, to write from user- and task-oriented perspectives, and to guarantee the use of a consistent terminology throughout the complete product documentation. These assets make technical writers indispensable for API documentation.

In other words, Parson sees programming skills as helpful but not essential, as the technical writer’s main value lies with other details in the user experience. At the same time, you still need a technical grounding to understand the basics of software programming.

Company size as a factor

Company size might also be a factor in deciding whether to be a generalist or specialist. In startups, employees wear more hats and need to traverse more technologies. In these startup environments, engineers often need to be more multi-faceted as well. An engineer who knows both front-end, backend, server, and other technologies is called a “full-stack developer.” According to Codeup:

… a full-stack developer is simply someone who is familiar with all layers in computer software development. These developers aren’t experts at everything; they simply have a functional knowledge and ability to take a concept and turn it into a finished product. Such gurus make building software much easier as they understand how everything works from top to bottom and can anticipate problems accordingly…. Often times, this class of developers stems from start-up environments, where a vast knowledge of all facets of web development is essential for a business’ survival.

When you work for startups, you handle more responsibilities than you would in a larger organization with a well-established tech pubs group. In startups, the generalist, or rather the “full-stack” technical writer, might not just be responsible for creating the documentation, but also responsible for the doc toolchain and publishing system, for support systems and forums, for e-learning and video creation, for blog posts and marketing content, information architecture and search indexes, and more.

Overall, the degree to which generalist skills are needed depends on the size of your company, and whether these other functions are covered by other specialists already.

Informal survey

Overall, what do we make of this debate about whether to be a specialist or generalist? It seems that there’s quite a lot of debate on both sides. I surveyed readers to provide agreement/disagreement about whether they think subject-matter familiarity is a key requirement employers are looking for. From about 55 responses, 50% agreed, 25% strongly agreed, and 15% were undecided.

I think it’s safe to say that employers are looking for tech writers who have all the skills they need — specialized knowledge and writing skills that span across categories and rhetorical situations, and more. In other words, employers want both someone to be both a specialist and generalist.

Technical knowledge valued more than writing skills

So far in this discussion about whether to be a specialist or generalist, I’ve made it seem like being a generalist is easy. It’s the specialized knowledge that’s hard to accrue. Presumably, a generalist is synonymous with a less-technical person whose strength lies with language and communication. Why do generalists seem to get less respect?

Imagine for a moment that you’re a hiring manager. You have two candidates for a tech writing position: a former engineer who has a strong technical background but little writing experience, and an experienced writer who has a veteran track record and extensive portfolio but doesn’t have strong tech skills. Who do you hire?

When I’ve been in situations like this, I’ve seen hiring managers (especially those from engineering backgrounds) choose the one with stronger technical skills and weaker writing skills. As long as the writing isn’t red-flag poor, hiring managers are willing to overlook more advanced writing skills.

In a recent post in the technical writing forum on Reddit, a user commented:

I work in engineering documentation, so I would always choose a candidate that has solid domain expertise even if they only have adequate writing skills. It’s easier to train the writing skills than teach the domain expertise. (“How much weight does a certificate in technical writing carry?”)

This sentiment is fairly common, especially among engineers. In Lanier’s research, he found that only 17% of job ads explicitly asked for writing skills; more commonly, job ads asked for specialized skills. Ellis Pratt says this might be due to the difficulty of quantifying and measuring writing skills. For example, it’s easy to check boxes if a candidate knows X, Y, and Z technologies but much harder to assess a candidate’s higher-level writing skills — his or her ability to create, synthesize, integrate, or distill large amount of complex information. You can ask for writing samples, but samples are hard to evaluate unless you know the product, context, and history of the documentation. So writing skills tend to be neglected in metrics for job ads, even though presumably this is the most salient skill that you’re hiring for, Ellis says.

At any rate, having “writing skills” doesn’t seem to resonate as much anymore because, presumably, everyone can write — or at least write well enough to get the job passably done. What’s important, it seems, is technical acumen and subject-matter familiarity, not stylistic flair. So you hire the candidate with an engineering background and address any style issues with an editorial pass — because it’s easier to teach writing than technical skills, some say.

In a recent issue of Communication Design Quarterly, Jennifer Mallette and Megan Gehrke argue that, in the workplace, subject-matter expertise with tech comm doesn’t seem to resonate as much as subject-matter expertise in technical skills. Mallette and Gehrke say that students graduate from tech comm programs with the naive belief that their expertise in tech comm will be valued in the workplace in the same way that engineers are valued for their expertise. They assume that in the workplace, exchanges between tech writers and engineers will be made from a position of equality, where the tech writer’s input will be valued and acted upon in the same way as engineers’ input. They’re led to believe that technical writers are specialists too, just specialists with language and communication. Different types of SMEs, that’s all.

Unfortunately, they found that subject-matter expertise was a status not available for tech writers, who were treated with less respect than other SMEs. Anyone could challenge or dismiss the technical writer’s decisions about content, as the product owner or engineer ultimately owned the content and carried the authority. Instead, they had to argue the rationale behind decisions, often resorting to making arguments by showing similar approaches in competitor’s documentation. This “power hierarchy,” where “where communicators are viewed as support or secondary,” is somewhat pervasive in the profession. It seems that very few engineers and product managers are willing to grant the holy status of SME to the technical writer.

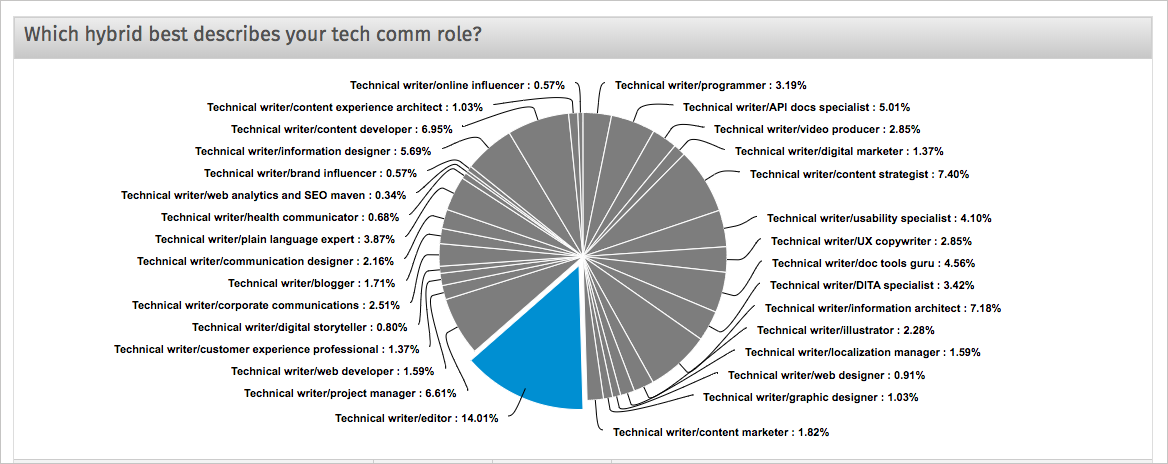

In my recent blog post, “If writing is no longer a marketable skill, what is?”, I noted (after comparing web metrics) that writing skills don’t seem to sell in the job market, so you have to supplement writing skills with some kind of hybridization to make yourself seem more valuable. I took a poll on my site to see which hybrid job titles were most common, and out of 277 respondents, the top roles were as follows:

- Technical writer/editor (14%)

- Technical writer/content strategist (7%)

- Technical writer/information architect (7%)

- Technical writer/project manager (7%)

- Technical writer/information designer (6%)

- Technical writer/content developer (7%)

- Technical writer/API docs specialist (5%)

- Technical writer/doc tools guru (5%)

- Technical writer/usability specialist (4%)

- Technical writer/UX copywriter (3%)

- Technical writer/video producer (3%)

- Technical writer/DITA specialist (3%)

Of course, these dual roles are self-defined only. In the HR books, one is usually still classified as a “technical writer,” but that’s not how we promote ourselves. Just being a “technical writer” isn’t nearly sexy enough to sell yourself in the technology marketplace. Technical writing has come to be viewed as wordsmithing only.

In the question about whether to be a generalist or specialist, it seems the generalist position (as it concerns writing) is much less valued in the workplace.

More complexity in technology is driving the valuation of technical knowledge

What exactly is driving the emphasis on technical knowledge over writing skills? If you consider an analogy from economics, technical knowledge is becoming more prized because it is becoming a scarce commodity. And it is becoming a scarce commodity because technology is getting more complex and specialized. It is the law of supply and demand at work in the enterprise, applied to knowledge. When very few people have knowledge of X, your possession of X knowledge can make you highly valued (assuming people care about X).

Because the technology landscape itself is becoming more complex and specialized, it is driving up the value of technical knowledge. How do we know if technology is getting more complex? In Implications of Tech Stack Complexity for Executives, the authors explain that one reason the technology landscape has shifted towards greater complexity is due to a transition away from single vendor systems. The authors explain:

Not too many years ago … technology stacks (the different layers of technology required to implement an application) were simpler and often vendor-specific. A good example is the Microsoft stack: .NET languages for programming, IIS as a web and application server, and the SQL Server database.

Today, technology stacks have exploded. We have platforms such as Microsoft Nano Server, Deis, Fastly, Apache Spark and Kubernetes. New tools pop up every week including Docker Toolbox, Gitrob, Polly, Prometheus and Sleepy Puppy. Programming languages and new frameworks such as Nancy, Axon, Frege, and Traveling Ruby are introduced. Advanced techniques such as the Data Lake, Gitflow, Flux and NoPSD mature. This list goes on and on.

They depict the change from single-vendor stacks to multi-vendor stacks as follows:

For companies to develop world-class software, finding the IT talent to develop these sophisticated solutions can be a real challenge, the authors explain. The authors say that “not only has the breadth of skills increased, but the depth of skill required (advanced versus basic) has increased also.” And given how quickly technologies are changing, you also need people who aren’t just locked in the present but who will “quickly acquire” tomorrow’s technologies as well.

In Overcomplicated: Technology at the Limits of Comprehension, Samuel Arbesman also expands on the trend away from single-solution systems to multiple-system solutions. Arbesman talks about how we’ve built systems that very few people fully understand, and these systems are interacting with other systems (often through APIs) in ways no one can fully predict. Sometimes when these complex systems have bugs (such as with Toyota’s acceleration problem), we end up scrambling through millions of lines of code across many different systems, trying in vain to find the problem.

Again, what’s the end result of this increased complexity? In software development contexts, technical knowledge is increasing in its value while generalist skills like writing are decreasing in value.

In a comical article called “How it feels to learn JavaScript in 2016”, Jose Aguinaga contrasts what it’s like to learn JavaScript today versus a number of years ago. His format is an imagined conversation between a newbie and advanced frontend developer. Aguinaga explains about 30 different confusing JavaScript frameworks and technologies that frontend developers need to sort through when coding. Aguinaga’s article illustrates how, for the past few decades (at least behind the scenes in the realm of JavaScript development), technology has been getting more and more complex and specialized — more extensive, varied, complicated, and diverse. The engineer who implements the frontend of a site has a very different skill set from the one working on the backend.

For contrast, think back to a time when we had “webmasters.” The idea of a “webmaster” — a person who handles all aspects of a website — is an especially dated idea, like a mechanic who can work on any model of car. Specialization has permeated all aspects of technology organizations. Today, you’re not just a “software developer.” You’re a JavaScript developer for web apps, you’re an Oracle database specialist, you’re a release management configuration engineer, and so on.

We have these specialists because complexity has increased. An article in the Harvard Business Review noted that we’ve even moved past specialization into “Hyperspecialization.” The authors explain:

Just as people in the early days of industrialization saw single jobs (such as a pin maker’s) transformed into many jobs (Adam Smith observed 18 separate steps in a pin factory), we will now see knowledge-worker jobs — salesperson, secretary, engineer — atomize into complex networks of people all over the world performing highly specialized tasks. (The Big Idea: The Age of Hyperspecialization)

The author notes that with some encyclopedia articles, even different paragraphs within the same article are sometimes written by different specialists. Each specialist-written paragraph fits together into a larger article.

Some might object that technology is getting simpler for users, which makes the job of technical writers easier because we write for users who are the recipients of these simpler UIs. The level of complexity depends on your audience, but generally technical writers are pulled towards complex systems rather than simple systems (which don’t need our help). You might be writing for internal engineers, engineers in other companies, or other professionals that aren’t engineers or end-users but somewhere else along the technology spectrum.

And for sure, some user interfaces are getting simpler (thanks UX designers!), but the code behind them is also getting more complex. The classic example of this shift towards simple frontends and complex backends is Google’s homepage. On the surface, it looks pretty simple. But go to View > Source and copy the code on that page, and then paste it into Microsoft Word. It’s 73 pages long!

Explaining available search parameters might be easy, but explaining the SEO algorithm behind the search is surely complex. The level of difficulty depends on who you’re writing for.

Consider another example: voice interaction. When I say to my Fire TV, “Alexa, show me the latest action movies,” this natural language interface attempts to simplify the user experience. There’s no need to find the right menu, to type out my search using the remote controller’s direction pad, and so on. End-users can just use their natural language.

But behind the scenes, making this simple language interaction has an incredible amount of complexity and code. There are multiple systems interacting in harmony with each other — or sometimes clashing, which can result in Alexa misinterpreting your utterance and returning something unexpected.

Technology is like an iceberg — seemingly simple on the surface for end-users, but with massive amounts of code underneath.

Trying in vain to keep up with the pace of technology

Looking at diagrams like those in the previous section strikes a bit of terror inside me because I realize how challenging it is to stay current in the evolving, deepening technology landscape. So often at work I find myself presented with some new topic to document (or even just edit) that I have very little knowledge of. It takes me by surprise, and I realize how endless the technology landscape is and how unaware I am of so many tools and languages, both code to concepts. Granted, Android app development for Fire TV (my main focus) is an extensive topic, but more often than not I’m constantly playing a catch-up game with what I need to know. It doesn’t help that the number of engineering teams I support seems to be growing every year.

If there’s one question that vexes me as a technical writer, it’s this: In this era of increasing technological complexity and specialization, is there any room for generalists like me? Do technical writers, who are typically only familiar with the subjects we write about, need to become engineer-like specialists, focusing in on a couple of domains in depth, so that we can write, edit, and publish more knowledgeably in these domains? Is specialization the only way to handle complexity? Will I need to become a specialist to survive as a technical writer in the future?

I’m not alone in this feeling of drowning in technology. In surveys I’ve done in the past, keeping up with the latest technology is one of the primary challenges for technical writers. About a decade ago (in 2007), I had a virtual chat with a group of tech writers to find out what their most pressing challenges were. Their most pressing challenges included the following:

- “For me, it’s keeping up with the right technology and fighting to increase productivity without making our jobs horrid.”

- “I have trouble keeping up with the rapid pace of innovation in the IT world and the many ways to deliver content.”

- “Part of the problem about keeping pace with technology is that we often work under tight deadlines. … at the end of the day, to learn new tools and technology, it’s often on your own time.”

- “I agree and I’m willing to learn about new tools and technology. The question is, where to start, what’s the right thing to get into? What do I recommend that the company invest in?”

- “Another problem with keeping pace with technology is the sheer variety of languages, systems, tools, concepts, etc. There is so much to know. One can’t know it all. But I think we have to be savvy enough to learn what we need to know at the moment we need it.”

Despite the need to accrue this more specialized knowledge, I’m still responsible for many different aspects of content, from the publishing toolchain and output to web analytics, information architecture, metadata, content strategy, and more across so many different categories of technical products. As such, specialization seems nearly impossible. At most, I can hope to possess a degree of technical acuity or aptitude that makes me mildly competent to collaborate with engineers and other specialists on the content. I have to say that being mildly competent doesn’t instill me with a great deal of confidence.

Finding the time to accrue specialized knowledge

How do you keep up with the need for specialized knowledge while also fulfilling your generalist writing role? In a recent post, I polled writers to find out how much time they felt they should devote to learning technology each day to be successful in their role. Of the 40 responses, about 30% said 30 minutes, 30% said 1 hour, and 15% said 2 hours.

But I also asked how much time they actually devote to learning technology each day. 27% said 0 minutes, 30% said 20 minutes, 19% said 30 minutes, and only 13% said 1 hour (see Strategies for learning technology – podcast recommendation and a poll).

Given how much technical knowledge you need to be functionally able to write documentation in today’s landscape, how can one possibly ramp up to the right level of knowledge by just spending 30 minutes or less each day? I felt I would need 2 hours a day to feel comfortable writing in some of these domains.

Even if you find the time, it’s not always clear where to start, as one writer noted. There is such diversity in what we document, it can be like moving from one long line to another long line in an amusement park — spending hours of learning just to be able to write one sentence that is read in 30 seconds.

In the end, who has 2 hours a day to carve out time for this learning, either at work or home? It’s nearly impossible unless you incorporate it into your job itself. But when I tried that, I found that my productivity plummeted.

Technical knowledge is essential to writing

Despite the difficulty in learning and keeping up with technology, technical knowledge is essential if you want to write documentation for engineers or other specialists. Without a comfortable understanding of the technical knowledge, your ability to write becomes crippled.

One approach to ramping up on this complexity might be to reduce your scope a bit and focus in on 1-2 projects in more immersive, in-depth ways than you could with 5-6 projects. However, it’s not always possible to reduce your scope. In one company, when we escalated concerns about needing more resources so that we could immerse and engage more fully with teams, executives responded by explaining that the company couldn’t afford to hire armies of tech writers, and that we had to “lean-in” on product teams to produce more of the documentation. In other words, we would act more like editors and publishers, while the engineers would do more content development.

Having engineers write introduces all kinds of problems (which I won’t go into here). However much I dislike the model where engineers develop content and technical writers add information usability, this just might be more common in years to come. If the content is so specialized that only engineers can fully articulate it at the required level, then technical writers will play more supporting editorial roles, guiding engineers with content creation and making the information more readable/usable. In this light, technical writers will continue to play more generalist roles (and be specialists in doc publishing or language only).

At conferences where I’ve given this presentation, one common response is to straddle being both a generalist and specialist by developing “technical acuity.” Through your technical acuity, you try to learn what you need to know with each project at the moment you need it. Someone with technical acuity not only possesses a technical mindset, he or she can self-learn the needed technical knowledge to the extent required for the documentation.

The problem with trying to learn what you need to know for each project is that it somewhat belittles the idea of specialization. For complex topics, the information builds concept upon concept over many layers. For example, consider a topic such as Advanced Calculus. Unless you’ve taken Algebra and beginning Calculus classes, you can’t just dive into a chapter in Advanced Calculus and totally understand something like “Lagrange multipliers” in 30 minutes. You have to work your way up from the earlier chapters and courses, climbing up through the layers until you have all the foundational concepts in place to make sense of Lagrange multipliers.

The same is true with Android programming, which is based on Java, which uses many common concepts from object-oriented programming. If you’re documenting, say, steps on how to incorporate the TV Input Framework into your app, you can’t just learn this in a morning without building the necessary foundation through many weeks or years in the more introductory layers of Java and Android. You can’t just skip chapters 1 through 50 to and absorb everything from chapter 51. At the same time, you’re rarely asked to document anything requiring information on chapters 1 through 50!

If you possess technical acuity, the assumption is that you might take your knowledge and learning in one category and apply it skillfully in another. For example, keeping with the math analogy, suppose you have a deep understanding of anatomy, such that you can draw, from scratch, all 206 bones in the human body and provide their Latin names. Does that help you learn Lagrange multipliers faster?

Your mind might be attuned to looking at system inputs and outputs, at algorithms that drive application logic, or more. Maybe you have a systematic patience for troubleshooting by comparing working code against broken code in a line-by-line fashion, or other troubleshooting insights. Do these skills allow you to jump categories and quickly absorb knowledge of, say, microchip design? Or of database querying? Would deep knowledge of Android allow you to, say, ramp up more quickly on changing the head gasket on your car? Or on understanding Heidegger?

I think in many ways, developing specialized knowledge gives you respect about expertise, which in turn helps you recognize your limits. My brother-in-law develops virtual reality games, but he won’t try to fix his car. He knows enough to recognize that he lacks expertise in that area, so he defers to the experts. Sometimes the more knowledge you accrue, the more you become aware about how truly complex a subject might be, and so you’re more apt to defer judgment to experts. This brings us back to this essential collaboration between technical writers and engineers. In a comment on my post on technical acuity, Mark Baker explains:

That is where the heart of technical communication lies, in the intersection of rhetorical acuity and technical acuity. The great debate in technical communication is whether that intersection can be achieved by a writer and an engineer working together, each bringing half of the equation, or whether it has to be by one person possessing both acuities. I tend to be in the latter camp. (“Preferring technical acuity over specialized knowledge”)

It’s an interesting observation – that the essence of our profession in tech comm is whether one can create content by having an engineer contribute the tech and a writer contribute the language, or whether one person has to manage both for success. Certainly, the reality is that this collaboration is done in varying degrees in different situations based on how much skill each party possesses in the other realm.

Possessing both acuities is surely the best route, but in my experience it isn’t practical. Learning how to skillfully interact with experts to gather, develop, and articulate their knowledge might be more essential than sometimes assumed. Being able to pull information out of engineer’s heads, knowing the right questions to ask based on the user experience, understanding how to iterate on content based on ongoing feedback, etc., might trump more one-dimensional technical knowledge. At any rate, this balance between specialized knowledge and generalist knowledge surely remains at the heart of the tech comm profession. It is an issue I continue to struggle with.

Your reactions and input

If you’d like to take a survey to help me understand how much you agree or disagree with the assertions I made in this post, you can take the survey here.

You can see the results (so far) here.

References

2016-2017 STC Salary Database (based on 2016 data). Society for Technical Communication. Retrieved Oct 2018.

Aguinaga, Jose. “How it feels to learn JavaScript in 2016.” Hackernoon. 3 Oct 2016.

Arbesman, Samuel. Overcomplicated: Technology at the Limits of Comprehension. Penguin, New York. 2016.

Baehr, Craig. “Complexities in Hybridization: Professional Identities and Relationships in Technical Communication.” Technical Communication Journal. Volume 62, Number 2, May 2015.

Brumberger, Eva and Lauer, Claire. “The Evolution of Technical Communication: An Analysis of Industry Job Postings.” Technical Communication, Volume 62, Number 4. Nov 2015.

Davis, Andrew. “Finding the right API Tech Writer?” SynergisTech. 20 Oct 2016.

“Documentation for Software Engineers.” Parson. Retrieved 26 Nov 2018.

Ep. 10: Information Architecture, Content Strategy, and Life at Etsy with Abby Covert. Brain Traffic. Date retrieved: October 9, 2018.

Grey, Jim. “Software technical writing is a dying career (but here’s what writers can do to stay in the software game).” Delivering software through leading people well. 16 June 2015.

Highsmith, Jim; Mason, Mike; Ford, Neal. “Implications of Tech Stack Complexity for Executives.” Thoughtworks. 16 Dec 2015.

“How much weight does a certificate in technical writing carry?” Technical Writing forum, Reddit. October 2018.

Johnson, Robert R. “Craft Knowledge: Of Disciplinarity in Writing Studies.” College Composition and Communication, Vol. 61, No. 4. June 2010.

Johnson, Tom. “Generalist versus specialist: What should you focus on with knowledge building in your tech writing role?” Idratherbewriting.com. 20 Dec 2016.

Johnson, Tom. “If writing is no longer a marketable skill, what is?” Idratherbewriting. 9 Aug 2018.

Johnson, Tom. “Number One Issue for Technical Writers Today: Keeping Pace with Rapidly Evolving Technology.” Idratherbewriting.com. 1 Mar 2007.

Johnson, Tom. “Strategies for learning technology – podcast recommendation and a poll.” Idratherbewriting.com 10 Aug 2018.

Lanier, Clinton. “Analysis of the Skills Called for by Technical Communication Employers in Recruitment Postings.” Technical Communication, Volume 56, Number 1. Feb 2009.

Mallette, Jennifer and Gehrke, Megan. “Theory to Practice: Negotiating Expertise for New Technical Communicators.” Communication Design Quarterly 6.3. 2018.

Malone, Thomas; Laubacher, Robert; Johns, Tammy. “The Big Idea: The Age of Hyperspecialization.” Harvard Business Review July-August 2011 issue.

Petersen, Emily January. “Articulating Value Amid Persistent Misconceptions About Technical and Professional Communication in the Workplace.” Technical Communication Journal. Volume 64, Number 3, August 2017.

Pratt, Ellis. “40. The evolution of the technical communicator’s career.” Cherryleaf. 2 Aug 2018.

Rhea, James. “Adding Value as a Technical Writer.” Within the Ordinary. 21 Dec 2016.

“Software Developers.” Bureau of Labor Statistics: Occupational Outlook Handbook. 13 Apr 2018.

“Technical Writers.” Bureau of Labor Statistics: Occupational Outlook Handbook. 13 Apr 2018.

Thangavelu, Poonkulali. “Companies That Went Bankrupt From Innovation Lag.” Investopedia. Retrieved Oct 2018.

Westberg, Hannah. “What is a Full-Stack Developer?” CodeupBlog. Retrieved 12 November 2018.