In the previous tutorial, we looked at embedding maps to help guide users through larger processes. But all the maps I showed were linear maps. What about maps for non-linear, complex systems? In this section, we’ll explore ways to guide users when defined paths don’t exist.

Adaptive information systems for adaptive user journeys

A complex system isn’t merely one that is technical or which contains many parts; it’s not simply a system that is “complicated.” A complex system is one that defies linear processes by including branching, conditions, feedback elements, many decision points, recursive processes, and ever-changing variables that affect each new step along the user’s journey.

In Content and Complexity, Michael Albers characterizes a complex system as follows:

Each new piece of data the user uncovers affects the path taken and the eventual outcome. … it does not lend itself to being performed with a defined set of tasks nor can those tasks be performed in a fixed order. … the step-by-step route to completing a task simply does not exist. … instead of following a set path, the user continuously adjusts their mental path as new information presents itself. … attempts to describe step-by-step actions break down because no single route to a solution exists. (“Complex Problem Solving and Content Analysis”)

In “Dynamic Usability: Designing Usefulness into Systems for Complex Tasks” (another article in Content and Complexity), Barbara Mirel gives an example of a complex system by describing a retail category manager trying to answer these two questions:

- “what mix of products should I stock to maximize profits and market share?”

- “what new product offering is likely to succeed in this market?”

The manager might run various reports, weigh different factors against each other, analyze trends and other conditions against the company’s budget constraints, and perform other hard-to-describe tasks to arrive at a conclusion. Each analytical activity can change the path the user takes. There’s a constant feedback loop with each input that affects the user’s next steps through a system — hence, no linear map is available for this journey.

In these systems, presenting the user with a linear map that consists of specific tasks won’t help much. Albers suggests that for these scenarios, the topics in the information system need to dynamically adhere together around the user’s specific and constantly changing context. By decoupling the information into separate, semantically identified pieces, Albers says these pieces can be dynamically assembled to address the context the user needs at a particular moment in his or her journey.

Again, this context and the user’s information needs constantly change as the user makes his or her way through the system (with feedback loops and inputs changing the path, or other chosen variables influencing the results). In this complex system where the context constantly changes, what information model can support the user? Presumably, only an information model that can adapt and change in similar ways to meet the evolving user context.

Sintering as an analogy

Albers says that a good way to understand this adaptive information model is by comparing it to “sintering” in ceramics. Sintering is the chemical process whereby individual components begin to naturally cohere into a connected structure. You can watch this one-minute video (that I found on Youtube) to see the sintering process:

How might sintering be implemented in an information system? Albers says that XML could potentially allow you to decouple and dynamically assemble the information, giving the foundation for this adaptive design. Albers wrote his article about 15 years ago, when XML was still emerging as a common technology (so keep that context in mind). He writes:

Only recently, with technologies such as XML, has information design gained the underlying tools to actually support complex problem solving in a general manner. With these new technologies, we finally have the means to break up the old contextual elements, recombine them at will, and present information uniquely focused on a problem. However, although the need to support complex problem solving is indisputable, we lack a clear methodology to support capturing the information requirements, reordering and dynamically constructing information to fit a situational context, and designing the interface for such a system. (“Complex Problem Solving and Content Analysis”)

In short, Albers wants to decouple information into individual pieces (just how granular, he doesn’t say) and combine them as needed based on the user’s changing context in real-time to address the user’s complex needs. His article is mostly theoretical — he isn’t specific about a particular design or approach to actually pull this off. You won’t find sample links to information systems or prototypes that would provide an example, nor more technical details about the implementation. It’s an academic idea, but one that has a strong appeal.

Albers continues:

…the requirements analysis cannot focus on defining a single path; nor can it define exactly which information is desired. Instead, the analysis must uncover potential information requirements and presentation methods.

What design most closely adheres to the information system Albers describes? Surely faceted navigation and filtered browsing could provide one model. Another model might involve showing a highly targeted selection of related links based on a particular user’s location, input, or context. I’ll explore each of these in the next sections.

Faceted filtering and dynamic assembly

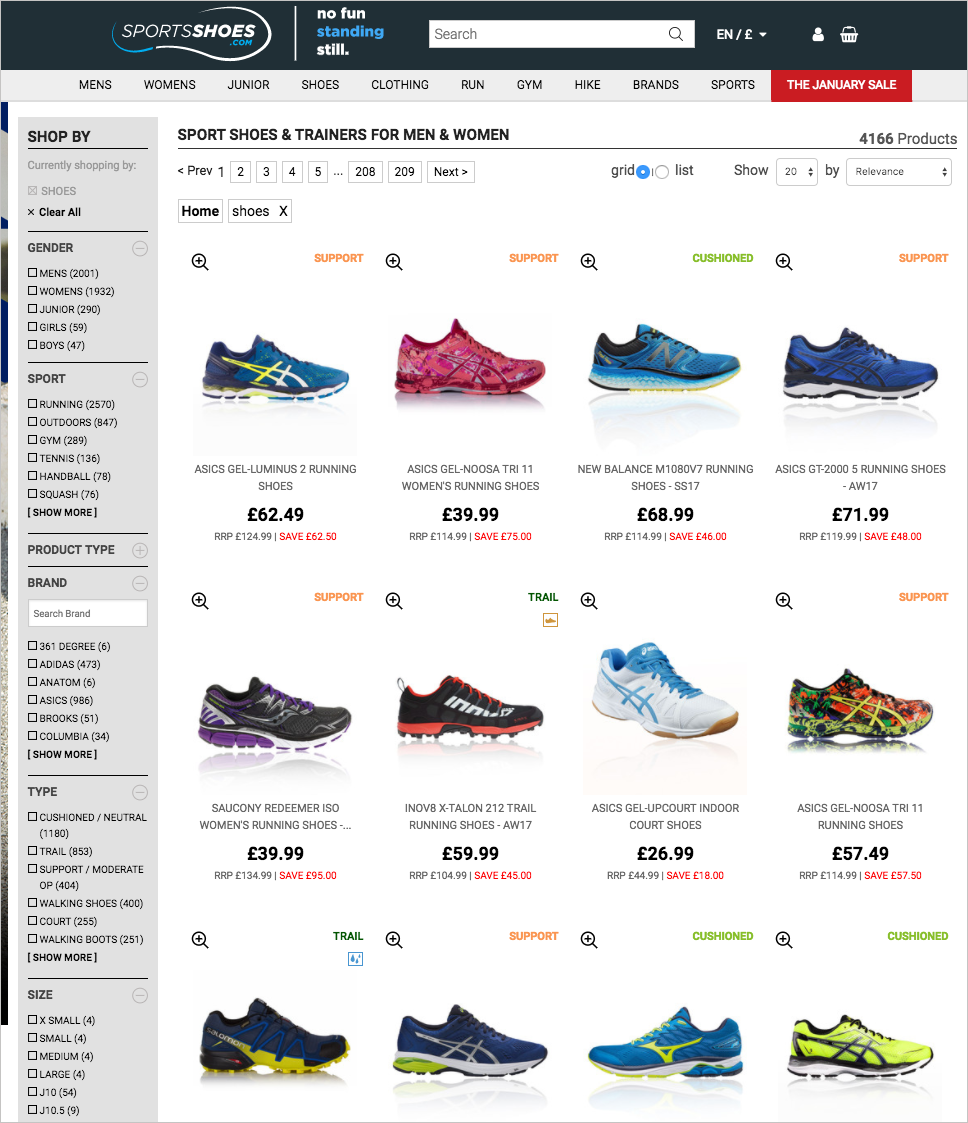

Step outside the documentation scenario for a moment and think of retail sites that contain thousands of products. It’s now a common design pattern to provide filters the user can select to dynamically narrow the products. For example, in this shoe site, sportsshoes.com, you can filter by about a dozen product attributes.

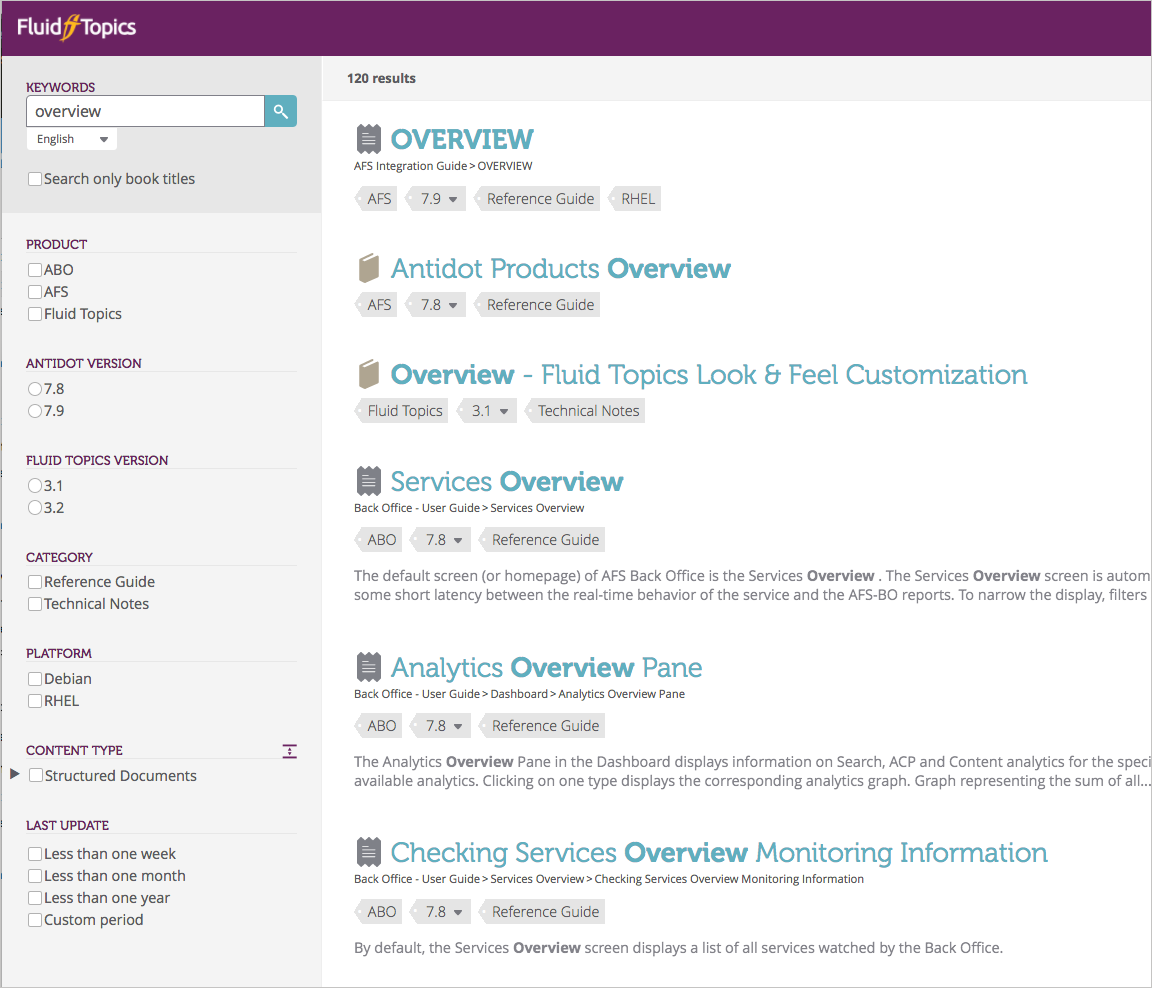

You see some faceted filters in documentation websites, but it’s not as common. Common filters might be based on versions, languages, or platforms. Here’s an example from Antidot’s Fluid Topics platform, which provides a robust documentation interface for facets by leveraging attributes related to the content.

I suspect faceted filtering would be more commonly implemented if the tooling were more available. However, beyond the attributes described here (product, version, category, platform, content type, last update), information systems tend to lack clear facets around which you can pivot the information. You mostly end up with keywords and tags.

In earlier posts on my blog, I explored adaptive displays of information through semantic tags quite a bit. For example, I based much of my 2013 keynote to the User Assistance Europe conference on faceted classification (see Making Content More Findable When Users Browse and Search).

I drank the Kool-Aid to excessive sugar highs ways when I read Dave Weinberger’s book, Everything is Miscellaneous. Weinberger argues that most everything we have defies classification; it can only be defined as “miscellaneous.” The classification schemes we use (from encyclopedias to planets, libraries, and other supposedly objective knowledge systems) break down. Each thing has characteristics that overlap with other things — a classification that makes sense to one person doesn’t make sense to another. There is no neat way to classify and organize the world’s information.

Rather than classifying information in absolute ways, or deciding what to include and exclude in systems, Weinberger argues that we should strive to add as much metadata to information as we can, and then manipulate the information in ways that make sense to each of us. (See my previous post, On Metadata and Help Content for a summary of Karen McGrane’s presentation and emphasis on the same strategy.)

Weinberger isn’t an XML consultant for documentation projects; in fact, he doesn’t even mention documentation systems in his book. His concern is at a higher level, with the general Internet as the playing field. But certainly, the idea of pushing and pulling content through metadata based on a user’s specific needs (with the context of the user’s profile, language, location, and other details) has made its way into the documentation landscape and serves as a key message in documentation conferences.

For example, a frequent theme in the Intelligent Content Conference is to deliver the right content in the right format on the right device to the right person in the right language, etc. In How to Get the Right Content to the Right People at the Right Time, Michele Linn explains that “this is what today’s content creators must aim for.” He lists the following ways content must align with the user:

- The right person to get

- The right content

- At the right place

- At the right time

- In the right format

- In the right language

- On the right device

These messages often accompany XML-related conferences, tools, or websites because one of XML’s key selling points is its semantic tagging and structure. Think of these qualifiers (e.g., “at the right time”) as attributes (metadata) that you associate with your content:

- audience (the right person to get)

- topic (the right content)

- location (at the right place)

- date (at the right time)

- format (in the right format)

- language (in the right language)

- platform (on the right device)

With your content appropriately tagged with this metadata, you can push and pull your content to target an audience that matches these same attributes. Semantic tagging is key to manipulating content into different arrangements at will to meet a specific user’s needs.

Chunking information

In order to manipulate your semantically tagged information, you might also need to chunk it in more granular ways. Consider a work that is one large book, with no chunks at all. In that case, it would be impossible to pull out pieces of information for specific scenarios because you have just one object (one order, one sequence, one path). With one object, the only chunk you can deliver is the entire object. But if you have a handful of objects, you can pull out just the piece you need for the situation. You can also manipulate the individual pieces in a variety of patterns and arrangements.

If you walk along the trails in Moab, Utah, where the sandstone and dirt ground makes it difficult to see a defined path, you’ll find many rock piles (“cairns”) that act as guide points. The cairns can be stacked and arranged in many ways, in many contexts for different needs and scenarios, because they consist of little chunks of granite.

(To read more about chunking, see my earlier post on this: The importance of chunking for sorting.)

If your goal is to manipulate content in a variety of nimble ways, pulling out bits and pieces to fit a specific user context at a specific time, you need to not only tag your content with the right metadata to surface such content, you must chunk your content in granular ways so that it can be extracted and delivered to the right user context. This leads us to probably the most recent application of this idea — chatbot design and digital assistants.

Chatbots and decoupled information

Today there’s a lot of excitement (and controversy) around chatbots. A chatbot provides an automated response to a message the user submits. You ask the chatbot a question, and it magically returns the right information (or tells you it doesn’t understand).

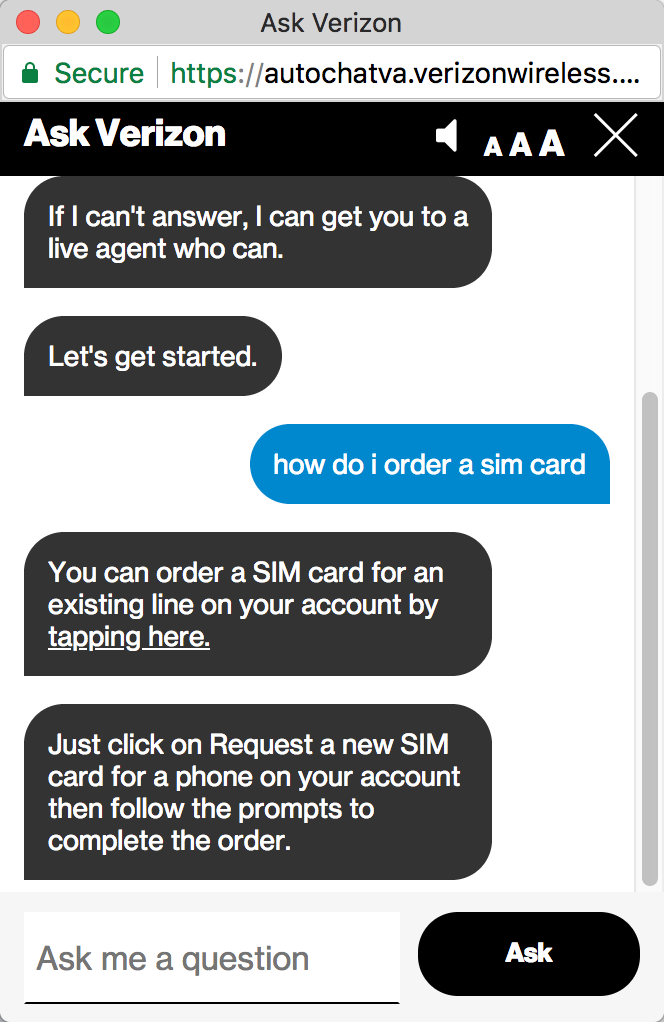

To try out a chatbot, check out Verizon’s “digital assistant” on their Contact page. Ask a question such as “How do I order a sim card”? and you get a response. In the following screenshots, my questions appear in blue, the chatbot’s responses in black.

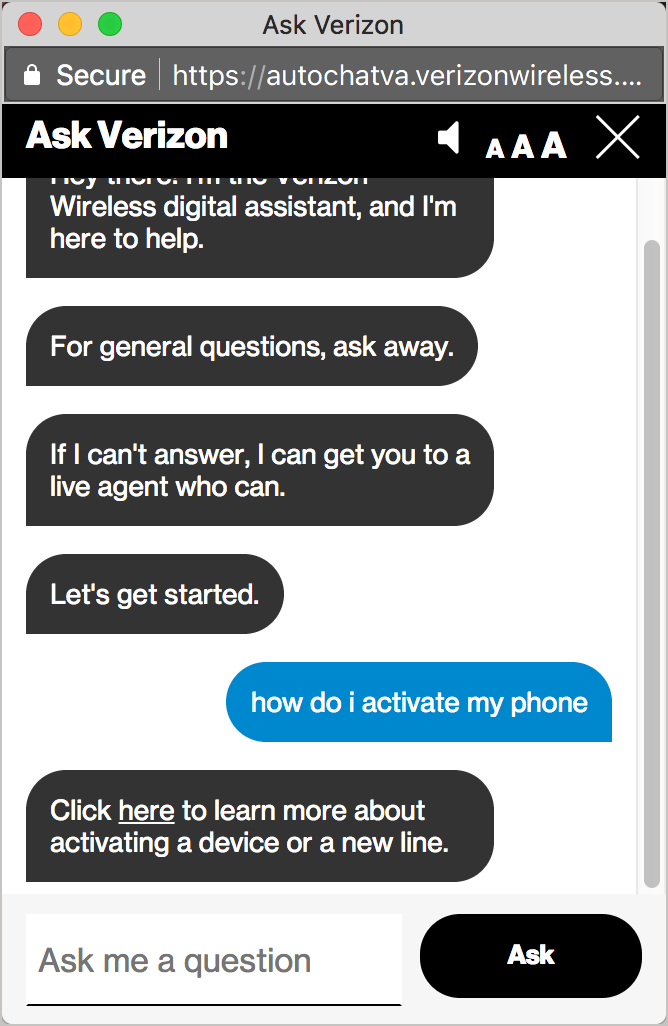

Or “How do I activate my phone”:

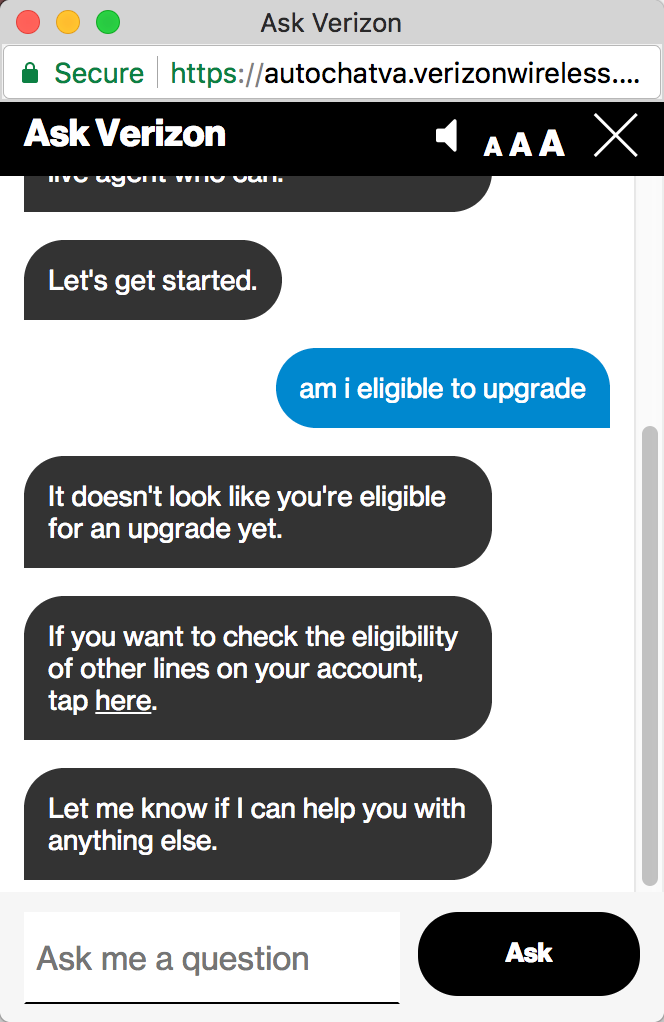

Or even something specific to your account, such as “Am I eligible to upgrade”?

The chatbot provides conversational AI for your questions. In order for the chatbot to return the right information for your context, your information must be chunked and tagged. The responses are the brief (1-2 sentences) and usually include links for more information.

Chatbots don’t have a standard format for structuring information. There isn’t a DITA or OpenAPI specification for chatbot information (which all chatbots then use). There are dozens of different structures, much of them in JSON. Chatbot platforms often use an API to request information based on specific inputs. In designing the chatbot, you have to map the user’s input to the returned information. The information is often returned through JSON and incorporated into the chatbot interface. (See wit.ai for more details on creating the mapping logic.)

The chatbot model works only if your information is chunked into granular pieces and tagged with the right metadata. Then these chunks can be summoned at will and inserted into the chat user interface.

Chatbots are mostly used in sales or support scenarios, and they provide relatively simple information on websites (like returning an answer from your FAQ, which arguably users could just as easily scan as text on a page). Chatbots have also been used in college pre-matriculation scenarios to help reduce “summer melt” (the tendency for students not to matriculate into college after being admitted). See Using AI Chatbots to Freeze ‘Summer Melt’ in Higher Ed and this NPR podcast.

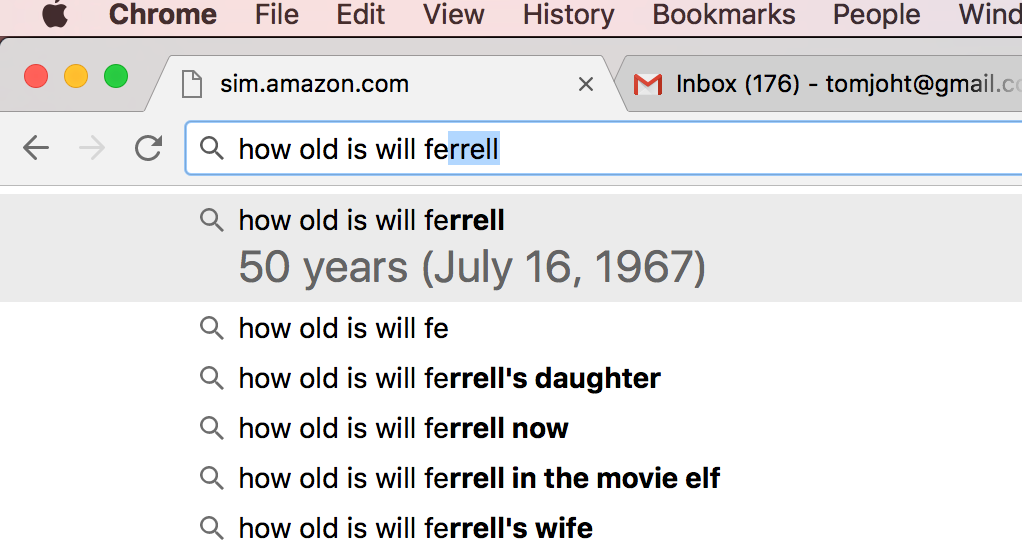

Google also seems to be implementing chatbot-like features in their search. For example, after watching some recent SNL skits that included Will Ferrell, I was curious to know how old Ferrell was (he looked older than usual to me). Google not only helped auto-complete my question, it also showed me the answer right in the auto-complete options:

The difference between search and a chatbot is somewhat merging here. Perhaps the only difference is that a chatbot provides more interactive, natural language processing (NLP) logic with search.

At any rate, just as you won’t find the entirety of a complex procedure contained in a search result, you won’t find complex procedures or concepts returned in a chatbot UI either. The Verizon digital assistant won’t even return instructions on how to activate your phone or how to replace your sim chip (relatively simple instructions). You won’t find instructions on how to remove an unintended line added to your account (my reason for visiting Verizon’s site in the first place), or how to fix incorrect charges from said line. Instead, you mostly get brief summaries or descriptions (FAQ answers) along with a link for more information.

Whether chatbots take off or not in documentation scenarios remains to be seen. Tech writers are in a good spot if their information is already chunked and tagged in a useful way. For example, if each of your topics has a summary, this summary can be useful metadata to return in a chatbot along with a link to the entire topic. In addition to the summary, tags such as the product, version, language, and platform can also be helpful, especially if the chatbot can match this information with a user’s profile in intelligent ways.

From chatbots to Internet of Things

Chatbots might be current hype, but the direction is not. The next trend after chatbots is pure voice interaction, such as with Alexa and the Echo. The Echo (a digital assistant device) is really just a chatbot without the screen (and it uses voice instead of text). Alexa is a voice platform for the interactions, and as a platform, Alexa can be implemented in other devices (not just with the Echo). With the Alexa platform, you can interact with your house, car, and the objects around you that don’t have little screens.

If you have an Echo (which has Alexa integrated), you can ask it questions such as:

- What’s the weather like today?

- What movies are playing?

- Who was Abraham Lincoln?

Or if Alexa is integrated into other objects, such as your bathroom mirror, your car, your home security system, Alexa can return information in similar ways.

Are you interested in working for Amazon as a technical writer to document Alexa? If so, check out the listings on Amazon Jobs. See Technical Writer, Amazon Alexa Automotive and Sr. Programming Writer, Alexa Skills. The locations are either Seattle or Sunnyvale. I like recommending qualified people, so [contact me]/contact/ if you’re interested, experienced, and want me to refer you.

We’re in the early days of AI, but there’s no reason to think the direction towards AI will change. Especially as more inanimate objects come online through the Internet of things, voice interactions will be the norm with these objects (especially if the objects lack screens). When you walk by your thermostat and say “I’m cold, can you turn up the heat a bit?” — what should the object respond? When you turn on your TV and say, “What new shows are available?” — how should the object respond? When you walk by a historical site and see a landmark and ask “What was here 100 years ago?” — how should the object respond?

For the AI-powered object to return a response, information needs to be chunked and tagged, ready to be identified and returned at will based on the context the user presents.

Internet of things (IoT) is all about bringing objects that were traditionally offline online. Not just bringing them online, but enabling them to interact with each other and with users. In the world of IoT, how will we design the responses of these interactions? Clearly, chunking content and tagging it with metadata will be a key strategy.

Challenges to writing chunked, tagged information

Conceptually, writing in small chunks that you tag and store as individual units seems like a great idea. But it’s hard to implement. It can be challenging to write coherent, rich content with this approach. If you chunk everything up into little bits, then you end up storing those bits separately. Your page just has references to each of the little bits. As such, you can’t easily read the page. You have to read the compiled version of the page to see the flow as a whole.

More challenging, you have to ensure that each chunk can have a consistent, understandable meaning when it’s dynamically assembled into any new context. This makes you think deeply about the context of each chunk, and you end up making the content more generic.

For example, chunking in a granular way constrains your ability to use links. Will the links always point to the right pages? What if the links point to the same page as the chunk itself? Antecedents (references to other elements) can also be problematic. If you write, “The code samples shown earlier demonstrate this approach,” you’d have to only use this chunk on the same page where “shown earlier” and “this approach” make sense. Depending on the granularity of the chunks, making sure the chunks always make sense in their embedded context can require careful, tedious analysis.

With content development hampered, the resulting content might not have the same rich story arc and flow as with long-form content. It depends on how granular you’ve chunked your content and how skilled you are at weaving together the independent chunks.

In an extreme example, suppose that for your content, you have hundreds of little chunks (either single elements or entire topics) that exist in a large database. Each topic might contain an assembly of those chunks, and each map might contain an assembly of topics. In our hypothetical information system, pages as such don’t exist, just a messaging and voice interface, ready to assemble the chunks in a dynamic way based on the mapping logic.

It’s a neat, futuristic idea, but it falls short for our goal, which is helping users understand a complex system. The reason it falls short is because complex systems by their very nature can’t be explained in isolated chunks of information. If so, they would be simple systems, not complex systems.

Learning is more than discoverability

Albers’ argument suggests that discoverability of the needed information is the key to navigating a complex system. If you can just find the right tutorial, reference, or other information to address the complex problems you face, you can make your way through the system (whatever your non-linear path might be).

To an extent, this might be true. But this idea makes a few assumptions. It assumes the information exists within the system to be found. It assumes that when the user finds the information, the user can recognize, process, and make sense of the information. Finally, it assumes the user actually knows the information he or she is looking for, and that the information can address the user’s scenario.

Facilitating information discovery is always good, but navigating a complex system involves more than just finding the right information. In Chatbots are not the future of Technical Communication, Mark Baker explains that learning is an “iterative process of refining our mental models until they fit the world as we are discovering it….” By mental model, he’s building on John Carroll’s rejection of the Nurnberg Funnel model, where knowledge is simply poured into users’ heads. In reality, users must “hack through the brambles of their own preconceptions,” Mark says.

In other words, even if the user is looking directly at the answer, the user might not recognize it or understand it because the user’s mental model doesn’t fit the information the user is seeing.

Mark explains:

learning is about rearranging our own mental furniture, finding our way through the thickets of our own minds. The expert can help us enormously at certain key junctures in that process, but most of it we simply have to do for ourselves. (Chatbots are not the future of Technical Communication)

The idea that navigating a complex system merely involves discovering the right information for your scenario (especially as delivered in snippets by a chatbot) is a bit simplistic and only addresses part of the problem. One would hope that good documentation would contain comprehensive, conceptual topics that do the work of re-arranging the user’s mental furniture. Theoretically, the role of the chatbot (or other voice-powered AI) is probably just to give you the right link to this topic. Currently, a simple search on Google provides a much faster and more efficient experience for discoverability; with excerpts on search results pages, you can quickly scan to identify the most relevant result. (See Mark’s Chatbots post for more details on the advantages of discovery through search and text.)

These little chunks of information (returned by a chatbot or other AI) won’t accomplish the heavy lifting required to re-arrange the user’s mental furniture. If you’re in a complex system, the concepts, workflow, and interactions are complicated and not easy to follow. As such, you’ll need in-depth, detailed help information that consists of lengthy content (often including illustrations, workflow maps, examples, sample apps, and more).

The idea that these complex systems can be navigated by showing the user the right chunk of information here and there (at a particular time and place) is somewhat superficial, given the current level of information returned from chatbots and other AI. Right now, about all chatbots are good for is converting measurements in the kitchen, finding the current weather, and playing a particular song. I’m not sure any of these granular chunks of content is going to help users understand complex products with any depth. Imagine trying to learn Calculus through a Twitter bot. Or trying to understand the General Theory of Relativity by looking at billboard signs, because chatbots return about the same amount of information. Isolated, small chunks of information aren’t enough to help users learn and master a complex system.

Metadata

Instead of thinking of decoupling our information into little chunks that can be dynamically retrieved and assembled, it might be more productive to think about describing our [probably lengthy] content with the right metadata to enable discovery. This metadata can at least lead users to the right topics, where they can drink deeply to get oriented and grounded.

How do you go about deciding on the right metadata? First, start by identifying all the scenarios where you want to present the user with specific topics in a way that will help him or her wade through complexity. Instead of brainstorming what metadata you should apply, think about the scenarios in which you want to summon the topics. Here are a few scenarios:

- Show the user getting-started topics for the product

- Show troubleshooting topics for a product

- Show all versions of a topic

- Show topics related to the current topic the user is viewing

- Show topics that other users (with similar profiles as the current user) found relevant

- Show the right programming code snippets based on the user’s platform

You might also have administrative scenarios for surfacing topics:

- List the time a topic was last reviewed, and by whom

- List all topics, by product, that require translation or which haven’t been translated in the past year

- List which authors and owners are responsible for a topic

- List which knowledge-base tags and articles are related to the topic

- List the 20% of pages that are viewed 80% of the time

Now that you have an idea of the scenarios you want to support, the next step is to identify the right metadata to support these scenarios. For this, it might help to have an idea of your system or scripts that you’ll be leveraging to actually retrieve the information.

Here are some ideas for metadata that a chunk of information might contain:

- title

- author

- product

- platform

- audience

- version

- content_type

- tags

- keywords

- description

- last_reviewed

- product_owner

- reviewers

- languages

- last_translated_{language}

Different metadata makes sense for different products, but this is a good start. The next challenge is adding all of this metadata to your pages in a consistent way, with a controlled vocabulary and the right data types. Some values, such as keywords, might make sense as arrays while other values can work as comma-separated values or single values. Some values might need to be integers (to work in scripts) while others can be strings. It depends how you want to manipulate the data.

With static site generators that use Markdown, you can add custom metadata to each page through YAML syntax in the page’s front matter. In other words, you don’t just have to adopt XML to tag your content with semantic metadata. Here’s a sample Markdown page in Jekyll with some of these properties:

---

title: My page

url: mypage.html

keywords:

- eggs

- bacon

- toast

description: A short description of the page

last_reviewed: 2018-01-20

version: 2.0

reviewers:

- sam

- sally

owner:

- barry

tags:

- configuration

content_type:

- how-to

---

Here's my page content ...

All the semantic tags appear within the frontmatter --- section. The lists that begin with dashes (-) are arrays. You can also include properties in your default configuration file (_config.yml) that apply selected front matter values to all pages in a particular directory. For example, product or author might be more appropriate to store in the default _config.yml file and apply the values to a directory as a whole.

Of course, if your platform is XML-based, you could probably add metadata to topics in a more robust way that you validate and enforce. However, with an XML approach, there’s more setup involved. You will need to validate both your metadata and structure against a schema.

This brings us to a larger question. Which metadata schema should you be using? If everyone just creates their own metadata, doesn’t that limit the metadata’s usefulness? Systems with different metadata can’t interoperate. Should we all be tagging our content with the Dublin Core metadata (created to describe web content)? How about Schema.org? Should we use the metadata schema in DITA? Should we adopt XML schemas appropriate to our industry (as is commonly done in Germany)?

Again, the answer depends on what you plan to do with this metadata and your content. Metadata is an entire discipline in itself. For example, check out the book Metadata, which provides a good introduction to different metadata schemas and approaches.

Although metadata can be useful to inform your own system’s discoverability mechanisms, ultimately Google tends to be the portal through which users search and find content. You can’t simply tag your content with the right metadata to move to the first page in Google’s search results. (Some meta tags in HTML, such as keywords, were abused long ago and therefore somewhat abandoned by Google.) You have to make your content SEO-rich, putting the right keywords in titles, headings, and summaries. You have to create rich, valuable content that others link to. And much more. Thus, does it matter which metadata schema you use if, at the end of the day, Google’s own algorithm determines what users can find?

How does tagged, chunked content simplify complexity?

Let’s return to our original problem: how do we simplify users’ paths in complex systems that defy linear order? A lot of these metadata tags, such as author or content type, won’t necessarily simplify complexity. But you can use metadata intelligently to provide a refined, short list of highly relevant content in the right context. I know that I’ve only scratched the surface here, but hopefully I’ve pointed the discussion in the right direction.

Questions for making information discoverable as the user needs it

- How will users discover this information?

- Is the topic SEO friendly for keywords that users would target?

- Are there places in the UI (or in error messages, etc.) where we could link to the topic?

- Could this be a related topic in other areas where users might end up, such as on other topics (as they follow the information scent in the docs)?

- What metadata attributes should this information have (audience, location, operating system, device, language, etc.)? How can we map this metadata to the user to surface this content more naturally to the user’s context?